Gavin Bryars’s soundtracks for Steve Dwoskin’s films constitute one of the major collaborations in the history of sound film, and their partnership belongs alongside Herrmann and Hitchcock, or Fellini and Rota. Times For, Dwoskin and Bryars’s first feature, made in 1970, which we are showing at BFI Southbank on Tuesday 1 February, was not their first collaboration, but followed a sea change in Bryars’s work, following a kind of apprenticeship with John Cage.

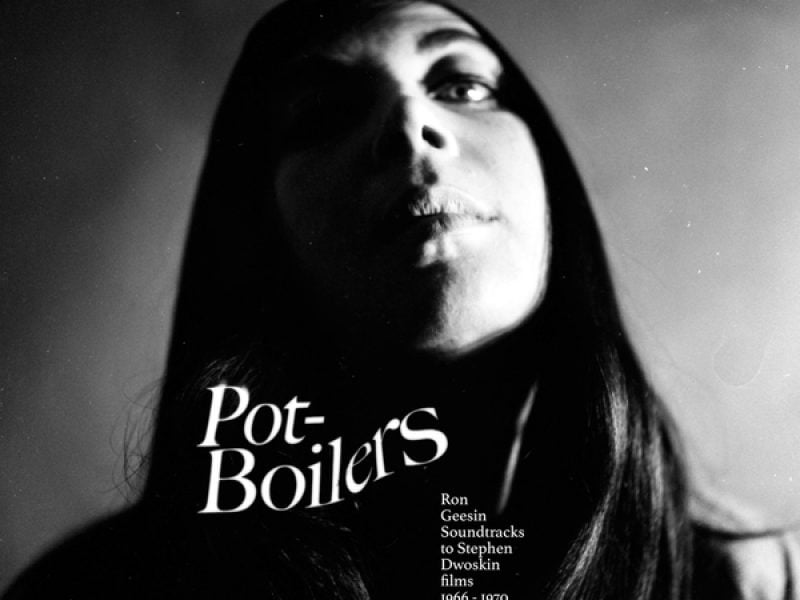

Bryars had first met Cage, briefly, in London, in the autumn of 1966, about the time he recorded his first Dwoskin soundtrack, for Naissant (1967), with Ron Geesin. On that film Bryars played double bass, the instrument he had been playing in the Joseph Holbrooke Trio, alongside Derek Bailey and Tony Oxley, during their journey from experimental jazz towards free improvisation, but which he now put back in its case.

In 1968 Bryars, having gone to the US as part of a collaboration with the dancer Powell Shepherd, met Cage once again, and the two composers, one a living legend, the other starting out, found themselves, by coincidence, at the University of Illinois. When Bryars’s visa ran out, Cage took him on as an assistant, helping him to stay in the country.

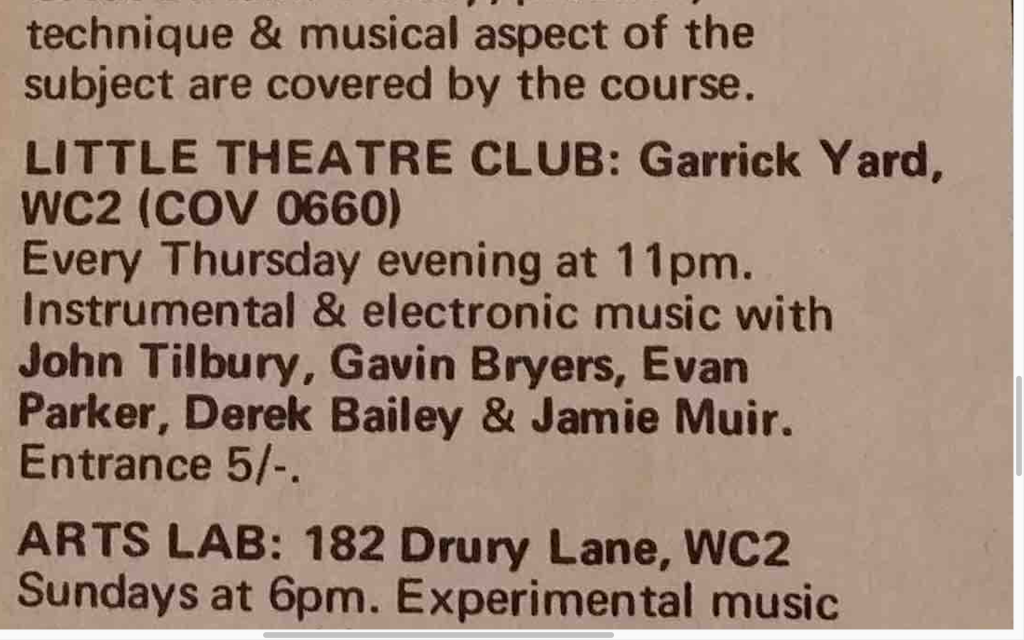

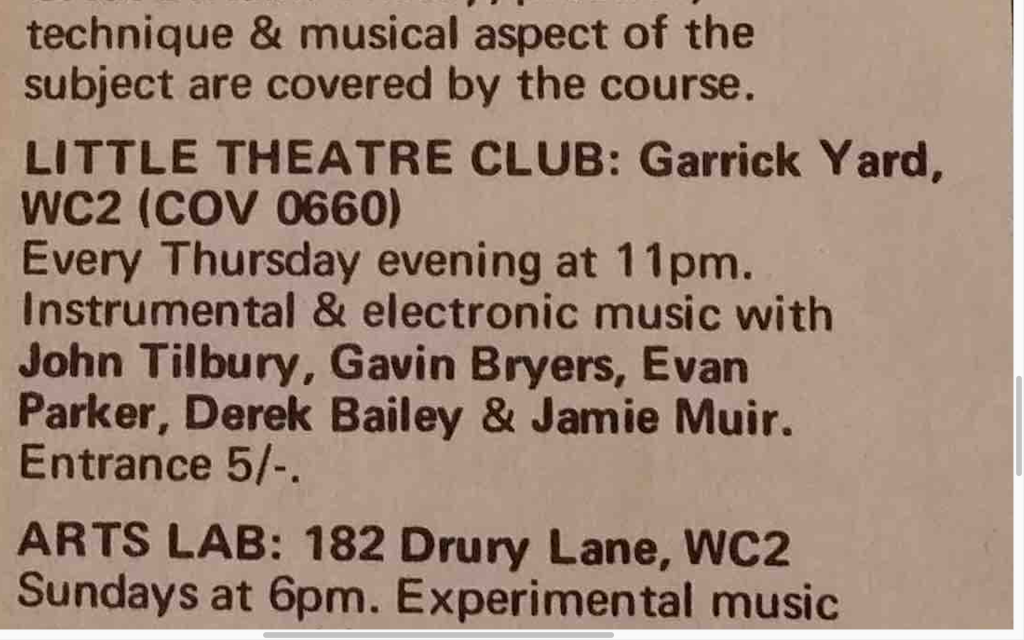

Time Out, October 1968

Back in London at the end of the year, Bryars set out on his new path, at a regular night at the Little Theatre Club, off St Martin’s Lane, alongside Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Jamie Muir, and John Tilbury. Whereas the first three were improvising in a “jazz, post-jazz way”, Bryars tells me, he and Tilbury were “working with percussion things and radios, and all that kind of post-Cage stuff”, embracing indeterminacy. Bailey recalled Bryars as bringing “a record of Tiny Tim which he might play five times in succession – no gaps.” Bryars, meanwhile, says that when he and Tilbury made a rare appearance on Radio 3, in October 1968, to perform the British premiere of Stockhausen’s Plus-Minus, he used a loop from the intro of Barry Ryan’s “Eloise”.

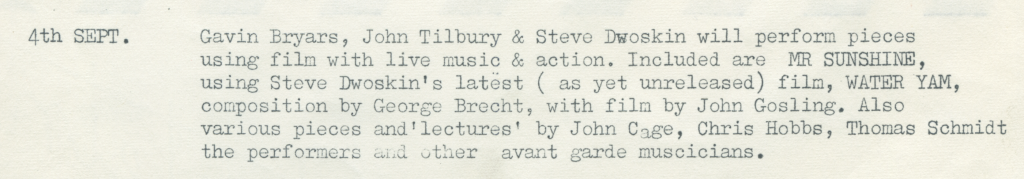

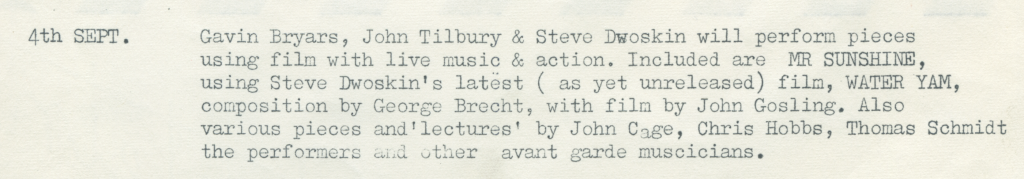

Bryars’s next collaboration with Dwoskin came in September 1969, at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, on a project that remains obscure but was billed as follows:

Edinburgh International Film Festival, 1969

It is unclear which of Dwoskin’s films was shown; possibly Moment, eventually soundtracked by Ron Geesin. “Mr Sunshine” is “a keyboard piece which can be realized in many ways”, a combination of loops, piano, and prepared piano, Bryars’s first acknowledged composition.

Geesin had done all of Dwoskin’s music to date, and all of Dwoskin’s films to date, with the exception of Soliloquy (1967), which is as its title suggests, had had soundtracks consisting of music and nothing else. This would largely remain the case after Dwoskin began making features, a move simultaneous with Bryars becoming his principal composer. Bryars compares their collaboration with that of Cage and Merce Cunningham. In a book Bryars read in his youth, The Bride and Her Bachelors, Calvin Tompkins wrote that the latter pair

shared many of the same artistic ideas, chief among them the notion that dance and music should not be dependent on each other, as they were in the work of other modern dancers, as well as in classical ballet, but simply two activities going on at the same time in the same place. Their method of collaboration was to decide in advance upon a certain time structure for a new work; then Cunningham would go off and choreograph movements within that time structure, and Cage, working independently, would compose a score to last the same length of time.

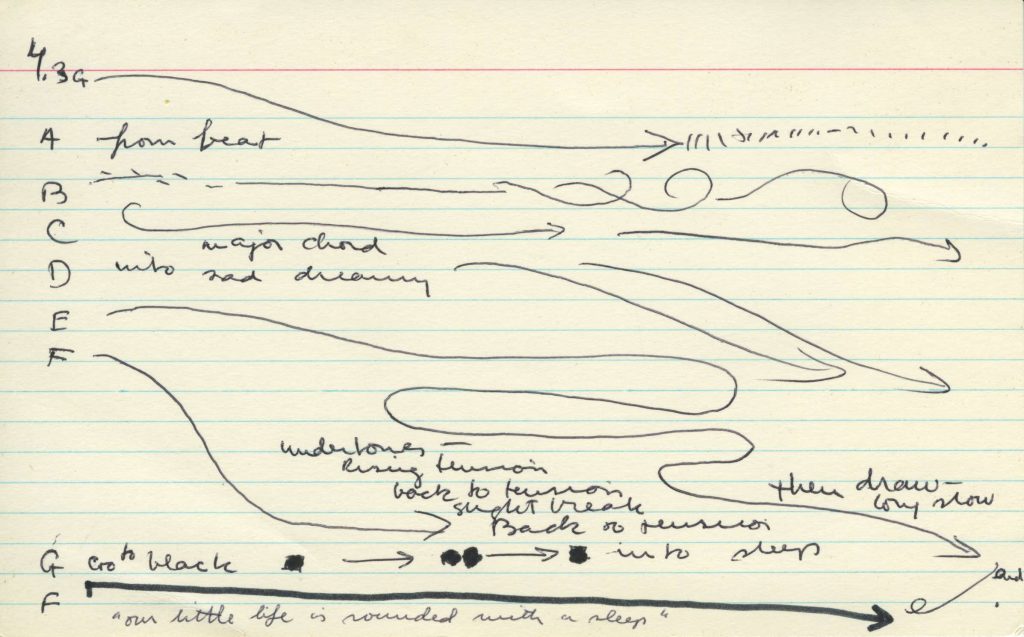

Times For is roughly divided into four sequences and an intro, or more specifically four women, four encounters with one man. While he was not aiming to synchronize music to film, Bryars recalls that he would be aware of the “energy” of each sequence before getting to work, but for the viewer of the completed film, the energy of the images is hard to distinguish from that of the music. The soundtrack establishes the pattern of Dwoskin and Bryars’s collaborations through the first half of the 1970s, which Bryars characterizes as “manipulating tape”.

The three main elements are drones; instrumentation, often toy pianos, toy organs, music boxes; and “found sounds, natural sounds, environmental sounds, what we now call samples”. He would cut loops with razor blades, and would mix not on a mixing desk, but by bouncing down from two audio tracks, occupying the two stereo channels of a Revox tape recorder, on to one mono track on a second Revox, meaning that, with each bounce, “of course it’s degrading all the time”.

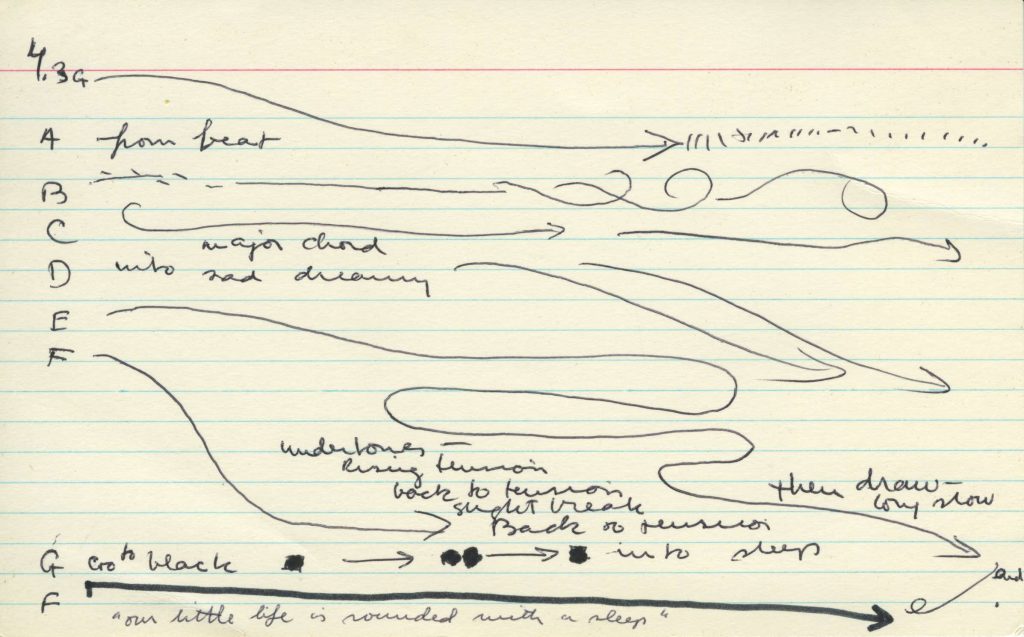

Unattributed notation for the last movement of Times For, reproduced in full in DWOSKINO: the gaze of Stephen Dwoskin

At the time of Times For, Bryars was living and recording in a shared house with Evan Parker in Kilburn; later, he moved in with Dwoskin in Ladbroke Grove, taking the place of Ron and Frankie Geesin (whereupon his place in the Kilburn house was taken by Brian Eno).

The first sequence after the intro, with Carolee Schneemann, is closest in spirit to the Little Theatre Club sessions, with manipulated pop records high in the mix. These would be phased out of the Dwoskin-Bryars collaboration, in the most dramatic way, at the start of their second feature together, Dyn Amo, released in 1972. Likewise divided into four sequences, four women, Dyn Amo begins with a conventional striptease, with the stripper played by Jenny Runacre, moving to records by the Rolling Stones, Marvin Gaye, and Phil Spector’s production of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah”.

Jenny Runacre in Dyn Amo

Jenny Runacre in Dyn Amo

The film turns decisively as Dwoskin’s camera goes into a tight close-up on Runacre, who returns his look, and as Bryars extracts a grinding loop from the Spector record – progressively mixed with guitar noise of origin unclear, and, later still, accompanied by a menacing drone and loop, auguring the film’s transition from something like reality into a dream or nightmare.

We are immensely pleased to say that Jenny Runacre will be taking part in a discussion with Dr Sophia Satchell-Baeza after a screening of both Times For and the first sequence of Dyn Amo, on Tuesday 1 February at 6.10pm.

XXX

The Dwoskin Project is based at the University of Reading and supported by the AHRC. Visit its website: https://research.reading.ac.uk/stephen-dwoskin/

The Dwoskin season runs at the BFI from 1 February. DWOSKINO: the gaze of Stephen Dwoskin is available now from the LUX.

Henry K. Miller is a senior research fellow at the University of Reading, author of The First True Hitchcock, editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat, and co-editor of DWOSKINO.