Myths and fairy-tales appealed to Dwoskin more than novels or plays, and there is a sense in which his whole career pointed towards Beauty and the Beast. In the early 1980s he had discussed with Angela Carter the idea of adapting ‘one of her “Fairy Tales for Adults” like “Bloody Chambers” and other short stories’ – the latter collection includes a version of the Beauty and the Beast tale – but the idea did not come to fruition until his last years. By the time he made it, in 2007, Dwoskin’s name was proverbially and disapprovingly associated with the ‘male gaze’, or a midwit idea of it, his films being all too obviously filled with female beauty; while he himself, over the decades since Behindert (1974), was increasingly prepared to show his own body at its most abject, beastly. Dwoskin’s ‘Beauty and the Beast’ has the feeling of a summing-up, a final statement.

The finished film, which debuted at Rotterdam in 2008, bears the title The Sun and the Moon; but it has a companion, Keja Ho Kramer’s The Beast Notes, that belongs alongside it, but which also stands apart. Kramer and Dwoskin began working on a project titled ‘Beauty and the Beast’ in 2006, in the aftermath of their collaboration on Kramer’s I’ll Be Your Eyes, You’ll Be Mine (2006), a film about her late father Robert Kramer, with whom Dwoskin had collaborated on a series of ‘videoletters’ in 1991. Keja Kramer had entered Dwoskin’s circle through the Belgian filmmaker Boris Lehman, when she was engaged as a translator on Lehman and Dwoskin’s never-finished collaboration Before the Beginning, shot in 2004–5. At that time and afterwards she was often living in Dwoskin’s home in Brixton, and edited I’ll Be Your Eyes on his equipment.

‘We would just talk about film all the fucking time, and all I had to do in exchange was – with great pleasure – cook dinner,’ Kramer recalls. Dwoskin had state-provided carers by this time, but had always relied on friends to get by. Kramer pays tribute to Dwoskin’s ‘magical approach to images’, digital editing in particular, which she contrasts with her father’s approach. ‘Steve had a way of working where the material accumulates, and then he would fool around with it and edit it, feel free to see how it moves – and then it would come together.’ Her own approach would be more ‘classical’, in her terms, but she remembers him as a ‘wonderful’, liberating teacher.

A ‘Dwoskin shot’ showing Keja Kramer in I’ll Be Your Eyes, You’ll Be Mine

In a dialogue they recorded in February 2006, published in Rouge, Dwoskin represented himself as unsure where to go next after Oblivion (2006), which he called a ‘big burnout’, a long film with many performers. ‘Beauty and the Beast’ was conceived for two (guess which), and The Sun and the Moon would have only three. Kramer recalls one of their starting points as being Bataille’s Madame Edwarda. According to a proposal they constructed:

The Beast has all the familiar human attributes but they are trapped in an altered body that creates anxiety, fear, and frustration. He perceives himself as an ‘alien’ that places itself in contrast to Beauty’s harmonious body – the breaking from idealization. She will overcome this in herself and be a dancer with the man who can only move with the machinery of the wheelchair.

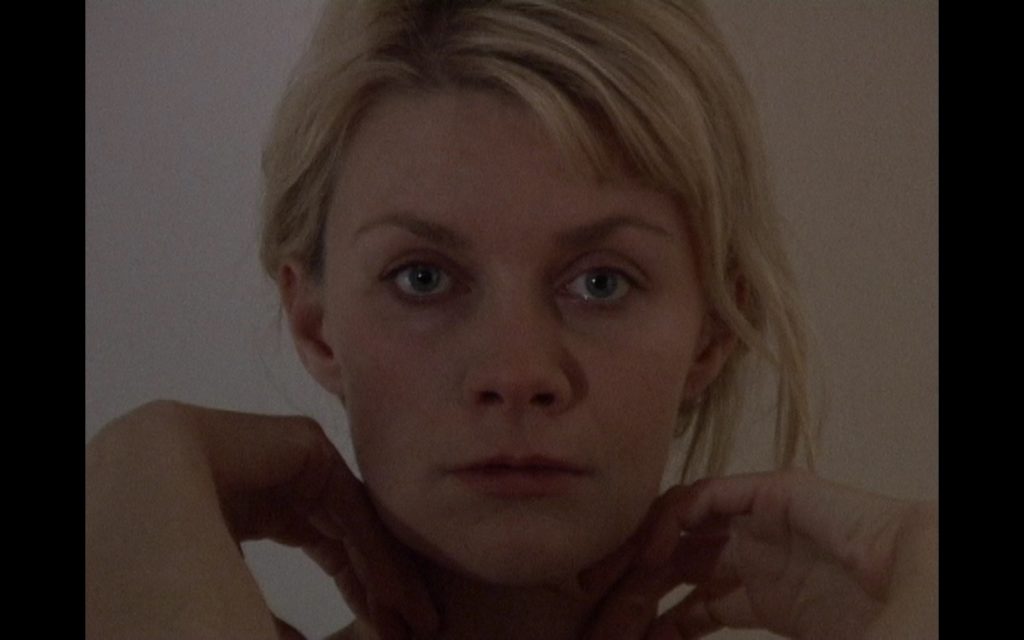

Dwoskin had long since passed out of the arena of the funded film, and like most of his twenty-first century works, the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ project would be self-financed. In the event, two Beauty and the Beast films were shot: Dwoskin’s The Sun and the Moon and an unfinished second film, with Kramer’s The Beast Notes film using footage from the latter. The Sun and the Moon was shot first, in January 2007, with Helga Wretman as Beauty, and Beatrice ‘Trixie’ Cordua, Dwoskin’s dancer muse since the early 1970s, as a half-beastly woman, seen mostly looking on in horror, making animal howls. Dwoskin appears in an oxygen mask, often confined to his bed, naked and exposed. Wretman had indeed trained as a dancer, and it was Trixie who brought her from Berlin to Brixton, and showed her Dwoskin’s earlier films. Wretman recalls that their routine was to order in an Indian takeaway, then film into the night. The film credits numerous Dwoskin associates with ‘images’, including artist Maggie Jennings, but Wretman says that she was shot by Dwoskin, and that many of Dwoskin’s scenes were shot by Trixie, uncredited.

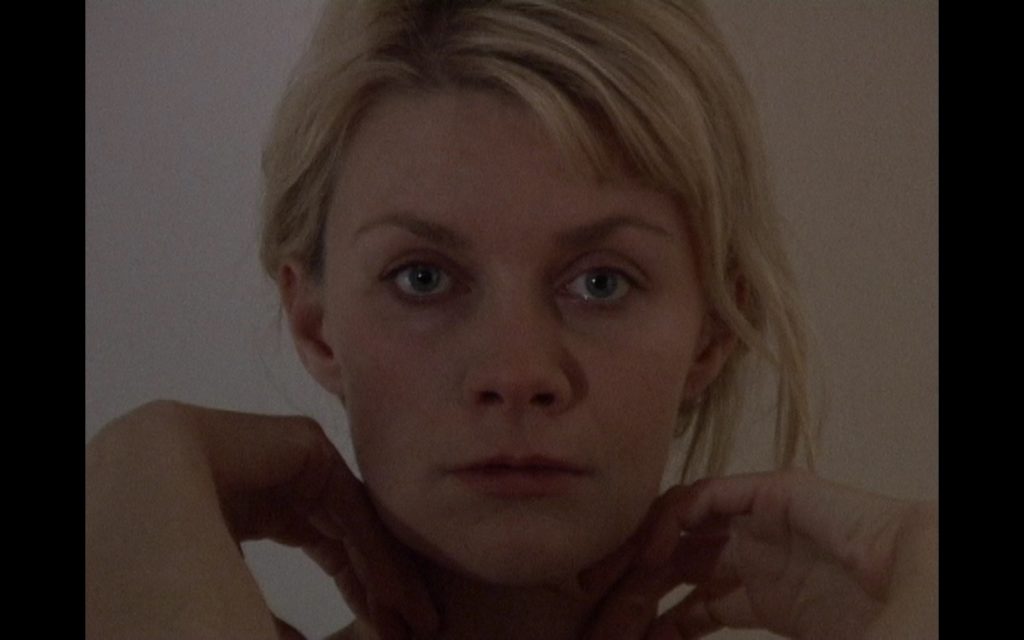

Helga Wretman in The Sun and the Moon

The second film, with Dwoskin and Kramer co-directing, was shot in March–April 2007, with Valérie Maës, an actress Kramer had discovered through a casting call in Paris; and it was from Maës’s scenes, including some that the two women had shot without Dwoskin, in the forest of Fontainebleau, that Kramer constructed The Beast Notes. Its title misleadingly marks it down as secondary. It begins in some ways like a ‘making of’ documentary, with Dwoskin and Kramer discussing an actress they have in mind, but as it progresses, the film slips its anchor, to move freely between modes – there are Maës scenes that would have gone into a different Beauty and the Beast film, and shots of Dwoskin directing them, but in this guise too he might be the beast. Whereas The Sun and the Moon is wordless, The Beast Notes makes its intellectual framework overt.

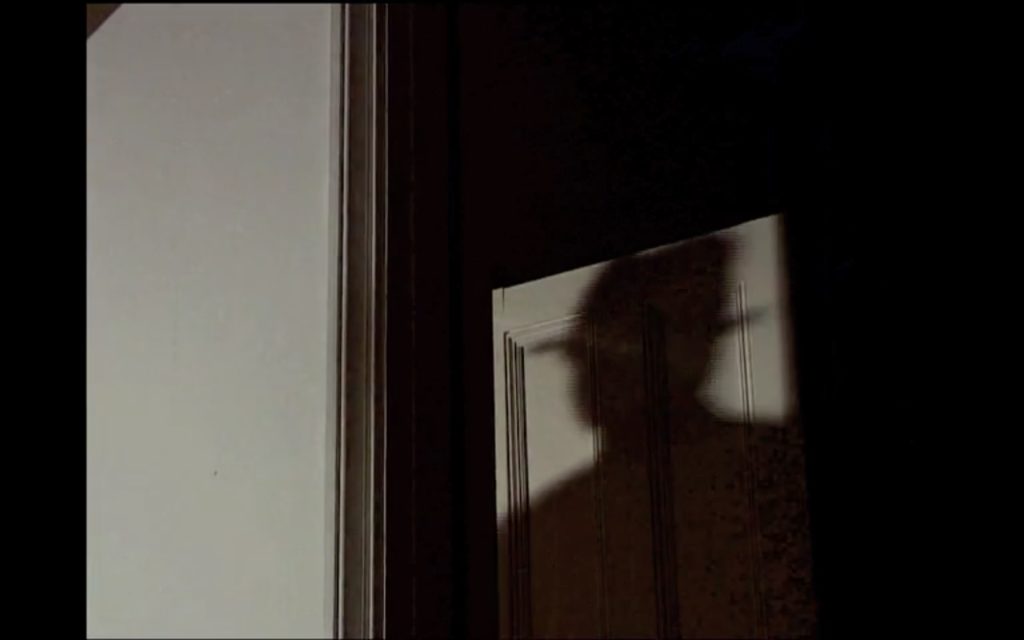

The Beast Notes was not the only outcome of the ‘second’ shoot. In the same year as The Sun and the Moon, Dwoskin premiered Ascolta! as part of a tribute to Puccini in the composer’s home town of Lucca. Using an aria from Turandot, Ascolta! is the last in the line of Dwoskin’s ‘face’ films, which began with the 16mm Moment some 40 years earlier. The face was Valérie Maës’s, shot (without Puccini) during the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ sessions, late at night – ‘Steven suffered from insomnia and I did too’, she recalls, writing that he would

shoot seated, the camera held on his knees, which required me to look into the camera, seek his presence there, and succeed in reaching him, meeting his gaze in this black knee-high box. And suddenly in this silence, eyes lowered towards the lens, something was operating, like a shift, an aspiration inside the camera, the camera as a room, a meeting place. The meeting of the (our) two gazes happened in the black box. I don’t know how it’s possible, and how Stephen knew that this shift could exist, but in this double-dive the gazes found themselves face-to-face in the camera, despite it being at knee height. And that evening, in the black box, it was the child Stephen from Trying to Kiss the Moon running towards the camera, a smile on his face, who came to get me.

Valérie Maës during the session that produced Ascolta!

When Raymond Bellour saw Ascolta! in 2009, he wrote to Dwoskin that it was ‘one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen on a screen, and my greatest souvenir of the Berlinale,’ a verdict he repeated in the pages of Trafic. ‘I know that you have shot a series of wonderful women’s faces, but this time, through the relation with the rhythm of the reworked music, it creates something really unique.’ The entire seven-minute film was created from half a minute of Maës’s work.

XXX

Henry K. Miller is author of The First True Hitchcock, editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat, and co-editor of DWOSKINO: the gaze of Stephen Dwoskin – available now from the LUX.