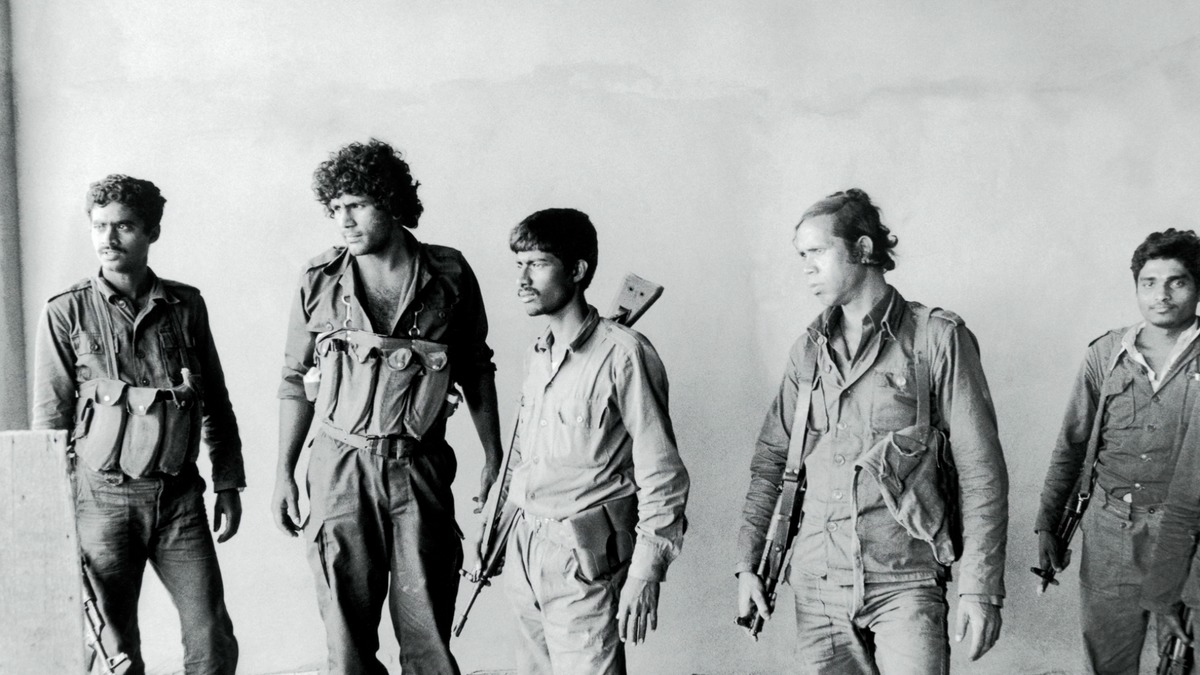

A photograph of five men standing in front of a concrete wall, somewhere in Beirut. Four hold rifles. One looks toward the camera while the others look beyond the frame, their faces lit by a light that reaches in from outside the image. “That special light,” a voiceover says. Apparently, in Lebanon in 1982, there were no tall buildings and the high clear Mediterranean light spilled everywhere. The light is not in doubt. It floods the photographs that pass one by one across the screen. But nowhere in the images can Naeem Mohaiemen find any trace of the Bengali men who, it is said, joined Fatah to fight for a Palestine they had probably never seen.

September 28, 1977. Hijacked flight JAL 472 sits on the tarmac at Dhaka airport. First, the plane is framed close to the nose, the camera set slightly above and at an angle that makes it look as if it’s about to slide out of the image, an arrhythmic composition, pulsing with the nervy signal of late 70s broadcast technology. The second shot is wide, the plane’s body stretched across the screen, wings clipped at the sides. It’s still sloping at an uncomfortable angle, nose pushed all the way to the left. Beyond the tarmac are hazy grey trees. The plane is weirdly still, the shot’s motion coming entirely from the juddering frame and electronic hiss of the radio transmission. Then follows a jerky zoom into the control tower where Mahmood, of the Bangladesh Air Force, is attempting to negotiate with the plane’s hijacker, a member of the Japanese Red Army, code name Dankesu. The solid lines of the control tower bend and waver. For the 6 days of negotiation, the images were simulcast to televisions around the world, an early version of a live terror feed. Nothing much happens. We watch as the airplane stairs are pushed along the tarmac, a thin strip of bitumen in an expanse of dirt and trees. There are shots of people standing around in the sunlight, the footage so grey their faces appear like ghosts; around them, undeveloped land. It had only recently been re-bordered to become Bangladesh. I imagine some of the people inside the plane had no idea where in the world they were.

A photograph of Sartre and a man whose name links three generations of the radical left. I rewind the film but still don’t properly catch his name. Something Klein perhaps? But then, a few minutes later, another Klein appears. Klein – one of them or perhaps both – becomes woven into a network of figures I know mainly as Hollywood characters: Andreas Baader, Carlos the Jackal, and then German politician Joschka Fisher, whose white sneakers seem unlikely to appeal to Hollywood’s sense of violent glamour. The thread runs from a deep thinker to glamourised violence to a pair of Seinfeld sneakers slipping toward an unsatisfactory centre. Something beyond the image leads to another image and then to another, each new perspective revealing the gaps in the image we think we’re seeing, the story we think we’re hearing.

I should be clear: Mohaiemen’s montage doesn’t act like Godard’s, where collage is frequently rhetorical. Nor is it dialectic. The multiplicity of perspectives Mohaiemen follows overlap and diverge at different points. In his use of history, things are both linked to and different from what has come before, so that instead of envisioning events as a repetition of the past, we start seeing them as transformations based on its echoes. Afsan’s Long Day (2014) begins with photographs from two protests held on the same day: one a leftist gathering at a University in Dhaka, the other by a group of young Islamists. The narrator observes the similarities between the young men at both protests – clothing, phones, a feeling of anger toward the imperialist West – but, despite the images being cut together, his observations don’t lead to an equivalence. Nor are the images matched graphically (they are neither match cut or linked through two similar gestures being placed together) in a way that might lead to that conclusion. When you start really looking, resolution becomes impossible.

A hand scrolls through a microfilm of back issues of the now defunct Far Eastern Economic Review “Mutiny on behalf of the people”. At first, the microfilm moves slowly, the shot is close to screen; the film scrolls and stops, as if the eye of the camera is searching for information. Then, a cut; the microfiche reader is reframed so its edges form a border on either side of the light-box, and then the pages start scrolling. Ads for The Globalist, American Express and air travel stand out. Images scroll like a strip of film, too fast to read, graphic. The archive becomes its materiality, a stream of marks set to a grid like bricks of information. Only, by now we realise that the views are partial, the reportage coloured by what the reporter doesn’t know. Later, there are shots of the archive itself – rooms of cardboard archive boxes, folders lined neatly on demountable metal shelving, labels indistinct. The physicality of the archive makes it look insurmountable, impossible to absorb. A history of dumb weight. But I’m not telling you everything. Under the images, Dutch journalist Peter Custers talks around (and he is hesitant, vague, aware perhaps of the insufficiency of words to express the gap between whatever it is he thought then and whatever it is he thinks now) his moral discomfort with seeking international protection when he found his situation in Bangladesh becoming dangerous. He chooses not to seek it. He ends up in jail on the charge of helping to orchestrate a coup he perhaps knew of, but only peripherally. He points to his insufficient knowledge as the justification for his choice, but there is something more that he never quite articulates, that it seems he still holds true – perhaps he didn’t seek help because his Bengali friends couldn’t activate the same privileges? On the soundtrack, Mohaiemen presses him. They talk it out, but something remains out of reach. The impossibility of interpretable logic is palpable. Is it the things that go unreported, unrecorded, and un-archived that drives our actions?

Why these images and not others? In the network of inflections that surround each event and image in Mohaiemen’s work, it becomes impossible to settle on anything certain. In the four films that make up The Young Man Was…(no longer a terrorist) (2012-2016), Mohaiemen’s Bangladesh is always on the brink of disappearing from view, a place on the periphery, documented by images that never really show what was happening. Lines are drawn and re-drawn, his characters sport mistaken ideals, false assumptions and ambiguous ideologies. His works are simultaneously complex history lessons and an investigation into history’s subjectivity. The mess of perspectives makes us aware that whatever it is we think about history, it is partial and flawed, based on the limits of our own particular experience and ideological leanings. Watching Mohaiemen’s work, I feel my own uncertainty, my own peripheral homeland. His films bring up memories. My father subscribed to The Far Eastern Economic Review, but, under the influence of the soft yellow light of my Australian childhood, what I remember are the Rolex ads featuring conductors, musicians and dancers – wealthy, Western artists who kept time. The distance between that experience and that of Mohaiemen’s subjects is incommensurable, but the complexity with which Mohaiemen creates his threads means that my images are added to his, as if together, artist and viewer, we are building a new map of the world, one with diversions and blank spots, a disordered topology glimpsed only in fragments, and, always, with doubt.

Sarinah Masukor is a writer and filmmaker living in Sydney. She is a presenter on ABC Arts online and in 2015 participated in the Gertrude Contemporary Emerging Writers Program. Current projects include a 21st century remake of Jean-Luc Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her.

![[sic], 2009, Eric Baudelaire [sic], 2009, Eric Baudelaire](https://lux.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/SIC15-edi_0-ptb8b5yid53olj96jrjmtt28342ke8xe3au1tmv3w0.jpg)