The film didn’t change much from its first assembly in 2020 and then it was a question of sending it to rights owners for their agreement. Those who knew Nico such as Richard Witts helped me locate others in her circle, Manuel Göttsching from Ash Ra Tempel who also gave his approval. Philippe Garrel was fully with the films I wanted to use, The Andy Warhol Museum and music publishers collaborated. I asked Philippe Garrel first as his portraits of Nico in his films are a big part of it. Then I approached The Andy Warhol Museum – these are powerful art institutions so naturally I was apprehensive, also about the publishers of the songs. I didn’t know where to start in that particular business as it is so complex. Archive producer Kate Griffiths counselled and guided me in this powerful world. It felt insurmountable. It was a huge task but it is a big part of the film. Obviously, I learnt a lot about production of archive, licenses and rights agreements. Although I have done it for my other films, this was on a different scale.

What did you learn about solitude, yourself, and your work in making this film?

‘Solitude’ is a reflection on film and started as reflection on a life in art when I was existentially facing death. Does a life of making art and films become an existential question when you approach the abyss? Nico talks about it herself “I’ve got close to it, so many times…it’s like you begin to see it. First when you are young it doesn’t exist. Then later, it’s a shadow, indistinct. Then you begin to recognise it as it gets close…’’ (in James Young’s ‘Songs they never play on the radio’)

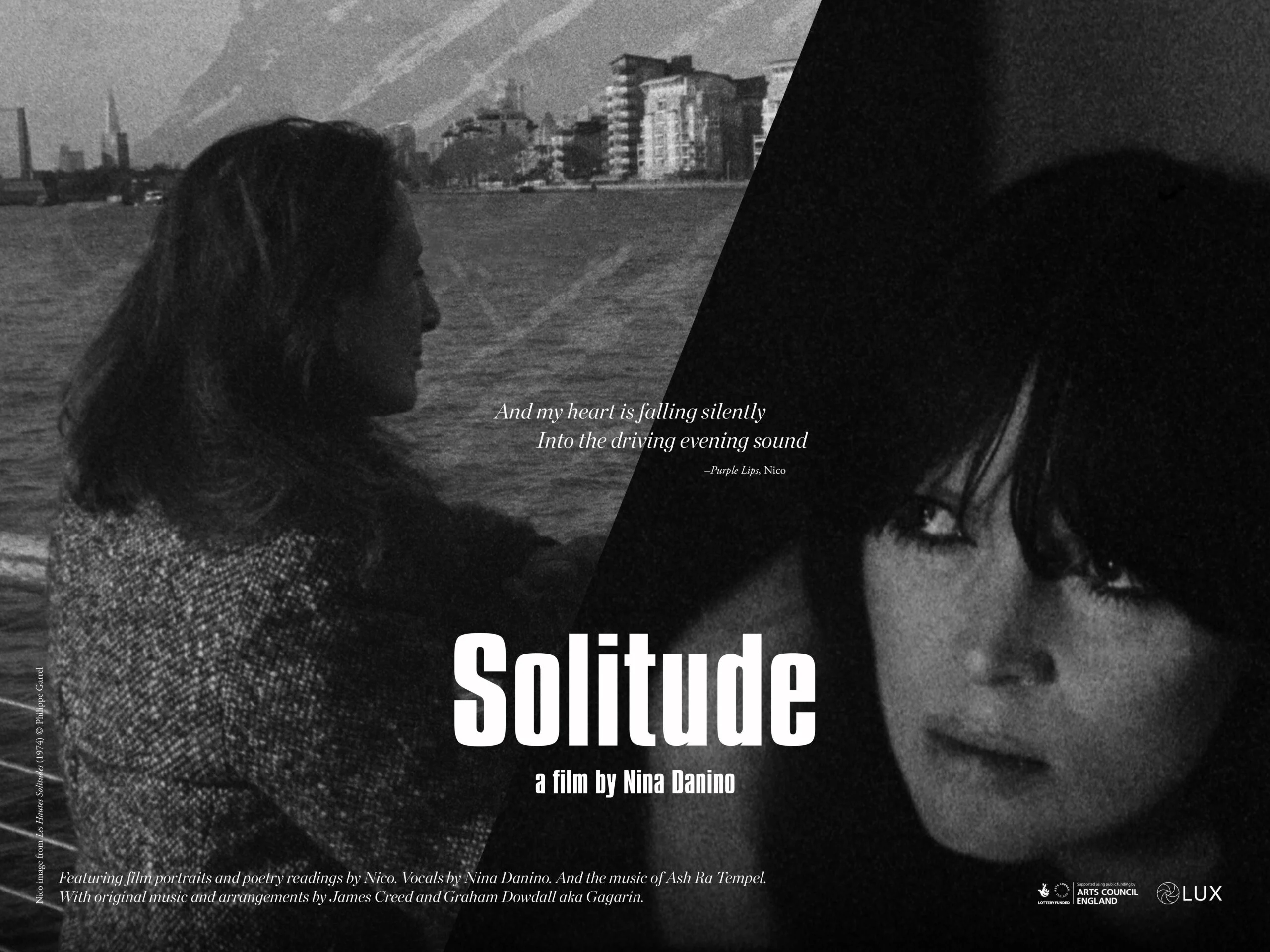

In ‘Solitude’ I am approaching these questions in a creative spirit of darkness not despair and bringing the imagination to dispel despair, which changes everything. I was grateful to have experience of film as a phenomenon which is a powerful medium, and such powerful materials and how the film is austere and has black intervals and uses duration and time is part of this experience. Graham Dowdall’s comment was that as a portrait it was true because Nico was unknowable and that is how I approached Nico as a screen and surface.

I learnt what an amazing singer and artist Nico was, that she is under recognised, and it happens to women. I hope that my encounter with her will lead others to think about her in this way – not just as a junkie woman but as the true artist and talent that she was. The more I think about her the more I admire her. She is very strong and led me through my own existential crisis which the film is a measure of. Thank you Nico, for calling out to me and stopping me in my tracks with your high-pitched calls in ‘It Was a Pleasure Then’.

I also really admire how she pursued her life in art. She did not receive recognition as a serious singer songwriter. She had the courage to re-invent herself after Paris, for the Manchester and London years that my soundtrack is really about. She came into her own as an artist in those years in my opinion, leaving behind the muse role and becoming the singer songwriter in post punk which she is credited as having created.

It also holds my story as a filmmaker, perhaps singer and artist and reciting famous Romantic poems rather than reading my writing or other prose, was something new. I had to think about the position and inflection of the readings and not to inject them with drama, to keep them even yet to add feeling. I realised that where I read them would substantially make me feel different and render a different performance. I did the readings twice. Once in a recording studio then again, in one take, in a church which provided the right ambience for the performance. It made me reach out to the spirit of the poems better. This also happened with ‘Janitor of Lunacy’ where the studio recording was fine but it needed more somehow, so I went to a local church on my own and up to the choir where the voice resonated from high above in a disordered way, thus in the spirit of the song and performance. It was also cathartic. Thus in ‘Solitude’ the spoken and vocals go in a performative direction and new collaborations.