Following my week at the archive in Taiwan I relocated to Hong Kong for the remainder of October. Hong Kong’s film culture is distinct from that in Taiwan and mainland China in many ways, primarily in the sheer diversity of productions enabled by Hong Kong’s relationship to a wide range of audiences throughout Asia. Largely free from political interference or persecution, the film industry was founded by exiles from both political spectrum’s in China.

This diverse industry saw Hong Kong produce films for Mandarin speaking audiences in mainland China (through companies such as the Great Wall, largely supported by people’s republic), as well as nostalgic pro-R.O.C. Mandarin films for Taiwan on top of a range of films for local Cantonese speaking audiences in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora throughout in South East Asia and overseas.

Given the large amount of freedom from government censorship or control, a wide range of independent production companies developed in Hong Kong dating back to the 1930s. Despite Hong Kong cinema’s reputation as a hyped-up, anything-goes version of Hollywood, it is an incredibly diverse film culture with different forms of alternative and independent film culture dating at least back to the 1960s not possible in Taiwan or mainland China until recently, through organisations such as the College Cine Club founded in 1968 and the Phoenix Cine Club in 1976.

Various works from this period are at the film archive (which held the important i-Generation film series in 2001 organised by video artist May Fung, surveying this area from the 1960s to 2001), and give an idea of some of the works made, even if they are hard to place when watched alone. The earliest independent films that are known to exist were made by photographer Ho Fan in 1960s such as Big City, Little Man (1963) which shows the contradictions in the life of distracted business man between his cramped traditional apartment and the commercial modern metropolis and the later black and white Home Work (1966) which shows the same suited protagonist moving through nocturnal Hong Kong and featured a great psychedelic party scene.

In a very different vein to these dreamlike allegories of modernity, is the minimalist 1966 film Quan xian/Across The Board directed by noted film critic and programmer Law Kar, shot from the window of a taxi crossing Hong Kong, the views are dictated by stop and start rhythms of the traffic and of the camera’s maximum shot length. Reminiscent of David Lamelas’s Time As Activity series (begun in 1969), the film presents a cross section of city restricted by the point of view, route and shot duration.

One of the most fascinating group of films I watched in the archive were a collection of super 8 political films documenting protests rooted in the anti-colonial movement that emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s. The British colonial administration’s move to raise the cost of the Star Ferry in 1966, the sole route from the Hong Kong peninsular to Hong Kong Island, sparked a series of riots and protests about the administrations disregard for its population.

A Place To Live: Small Boat (1979) an hour-long super 8 film made by the Society for Community Organisation, a human rights organisation founded in 1972, chronicles what critic Lui Tai-lok described as the ‘most notorious and momentous social conflict in the late seventies,’ following the campaign of the Yaumatai boat people to be resettled on land. Showing the development of the protest from a localised issue to one which is supported and championed by the broader student and anti-colonial movements, the film provides a remarkable insight into the attempts to establish basic human rights for all of Hong Kong residents.

The more militant protest movement, which was aligned with the Cultural Revolution in China, was established in relation to the questions of the sovereignty of the Diaoyutai islands, a collection of largely uninhabited islands in the East China Sea northwest of Taiwan. Claimed by the Japanese during their occupation of Taiwan, and administered by the United States after WWII, the island was controversially returned to Japan by the American admistration in 1971 which sparked the anti-Japanese, ‘Defend Diaoyutai movement.’

This movement shows the complexity of political identity in Hong Kong and its relation to the People’s Republic of China. A super 8 film by Lau Fung-ji, Demonstrate (1970s) presents a public meeting of the ‘Defend Diaoyutai movement’ in Hong Kong juxtaposed with May 1st protests in Hyde Park and pro-Mao campaigners in London, showing the contrast and similarity between these political demonstrations. Posters in Chinese and English, such as one which declares that ‘The United Nation’s Is Not The American United Nations’ are direct critiques of the foreign handling of Dioyutai issue, a territorial issue related to unresolved issues of Japan’s treatment of the Chinese during the second world war.

At the Hong Kong Arts Centre the spectre of political protest and action was present throughout a weekend of performances as part of Action Script , a series exploring performance art in Asia organised by the Asian Arts Archive as part of its 10-year anniversary. The ‘Defend Diaoyutai movement’ and its nationalistic associations were challenged by Mok Chiu Yu during his performance Feeling Young and Subversive.

While having his white hair dyed he read Charter 2010, the human rights statement written by recent recipient of the Nobel Prize, Liu Xiaobo (currently under house arrest in China for his political activity) and others. Designed to be circulated and presented in a range of contexts, including performance art, the document proposes radical changes to Chinese society for the 21st century.

As well as reading the Charter, Mok Chiu Yu played one of the original protest songs of the Diaoyutai movement, in order to critique the nationalism underlying the movement and the way it was been manipulated in recent years by the Chinese state, especially following the recent incident in September 2010, which saw state endorsed anti-Japanese protests. Mok Chiu Yu, concluding by declaring the islands, whose name Diaoyutai in Chinese and Uotsuri in Japanese literally mean ‘fishing’ islands, belong to neither country but to the turtles and fish, their only real resident.

The weekend featured a cross-section of performers from across Asia, including works such as the Hong Kong-based artist wen yau’s ‘Homage to Seiji Shimoda: On the Table,’ a re-staging of the famous performance by Seiji Shimod, founded of the Nippon International Performance Art Festival (NIPAF), in which the naked performer traverses a table top and underside attempting not to touch the floor. This work and others resonated both with the issues of documentation and interpretation central to the weekend and the AAA as a whole.

Outside the HKAC, Thai artist Chumpon Apisuk, held an umbrella offering shelter for whomever sat under it, a minimal intervention and a durational performance similar to Hong Kong artist ger Choi, who appeared to be performing a symbolic action, stood on the lower steps of the nearby overpass, circled her head with one hand while stood entirely still.

On closer inspection you could you see that ger Choi was unraveling a cotton thread around her neck building up a thick black band slowly restricting her breathing. A pair of scissors at her feet offered the potential of release, but two nervous spectators who cut the thread had no effect as she merely reattached the loose end and continued. Both performances in their stoic resolve could be understood as political actions in a region were public dissent continues to have serious ramifications.

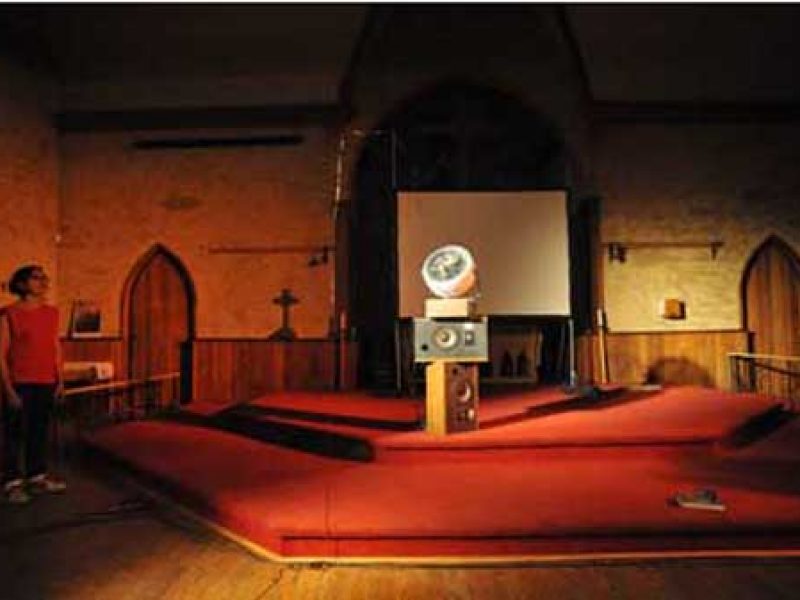

At Para/Site Art Space, ‘Sharp/Clear/Deep’, a show curated by Rirkrit Tiravanija, ‘sought to explore the ‘double-edged confrontation between the established institution of bureaucratic urbanism and the grassroots ruralism of peripheral under class.’ As part of an exchange with gallery VER in Bangkok, the project presented works exploring the contested notion of tradition and national identity in Thailand, organised in part around work by the Thai artist Montien Boonma (1953-2000), who explored national identity through his use of local materials and techniques to stimulate and question the senses.

Members of the artist collective, As Yet Unnamed, Charit Supaset, Disorn Duangdao and Worathep Akkabootara presented works responding to Boonma’s use of local materials in the context of the current re-politicisation of notions of tradition in Thailand. For example Supaset questioned craft through an investigation of knife-making, a practice performed for the opening and then the finished blade was displayed as both a found object, a record the of process and an contested example of ‘ethnic’ art.

Nico Dockx and Rirkrit Tiravanija’s sound work erasing 22’09” (unfinished), 24.05.2010, a collaboration performed during the cleanup of the recent political protests in Bangkok described by the artists as a dual act of ‘aestheticizing and obliterating’ an image. The piece, which features sound recordings of the collaborative drawing and erasing of their copy of a documentary photo, explore the problematic nature of public record and history within the political context of Thailand and its ruling monarchy.

Repressive governance permeates South East Asia, in the remnants of colonialism or militaristic nation states, to current suppression of rights on ethnic, religious or linguistic grounds. Singapore-born Chinese performance artist Lee Wen’s Anyhow Blues (pictured above) was situated somewhere between a public lecture, music performance and protest, and this attempt to find a way to address the death penalty in Singapore was one of the most intelligent, funny and effecting of the Action Script weekend, and ultimately incredibly moving.

His performance appeared disorganised, with several false starts. He stating the he had planned an action, but changed his mind and instead would tell some jokes and sing some songs, then stopped himself and apologised for speaking in English, saying he’d just done a whole talk in France and no one told him they didn’t understand English until the end.

Lee moved around the floor, his balance and mobility effected by early stages of Parkinson’s disease and talked about some of his projects in which he’d attempted to find ways to talk about human rights in Singapore, before changing abruptly to the subject of capital punishment and the murder of working class people acting as drug mules across the region.

A legacy of the British government, Singapore had the highest per-capita execution rate in the world, mostly related to drug offences, between 1994 and 1999 , since then official numbers have been suppressed. Lee presented the banned book, Once a Jolly Hangman: Singapore Justice in the Dock, written by the British author, Alan Shadrake, who was on trial in October and as of 2 November convicted of contempt of court because of allegations in the book.

As part of his action, the book was presented together with a pig foot from a butcher. With help from the audience, he tied the foot to his wrist before performing a version of I am a Patriot, an American protest song by Little Steven. Recast in the context of conflicted state of Singapore, where civil protest is only possible in absurdly restricted circumstances, and interrupted by Lee’s instruction to his friends in the audience not to cry, it was a powerful reflection on the contemporary status of politics, expression and history in the region.

George Clark is a London and LA-based curator, writer and artist.