A relaxed atmosphere pervades the Images Festival in Toronto. Its programme is split in equal parts between exhibitions, screenings and live events which are generally presented in the evening, leaving plenty of time to actually get around to the many venues across the city during the festival’s 10 days.

Steve Reinke’s participation in Images on many fronts is a particularly apt example of the various platforms of the festival. As well as presenting his new hour long video The Tiny Ventriloquist, he also had an exhibition and book launch. The video is a typically complex and challenging assembly of material exploring different forms of address from the artist’s voice, to found videos and abstract animation; one scene in particular which traces man’s relationship to animal through a found video, overlaid in part by Reinke’s animation yet still disturbing, in which a female hunter kills a bear and then has sex resting on its caress, is central to the videos attempt to describe a post-humanist consciousness. The installation The Root Problem of The World deconstructs a Joseph Beuys 1976 lecture delivered prior to receiving an honorary doctorate at NSCAD in Halifax, Canada. A typically decisive yet ambiguous commentary on language and art, Reinke edits and re-presents word by word fragments of Beuys’s lecture, in which he states that ‘language is an object’, intercut with his laughter and snippets of Krautrock. Reinke’s new collection of writings, The Shimmering Beast,, also launched at the festival, allows a greater involvement in his explorations of the voice and the potential of first person address with stories ranging from the banal details of familicide in History of Small Animals, to his ironic commentary on the idea of ‘queer space’ in Camping (On The Beach). “None of it is autobiographic or confessional,” he declared in a talk with fellow Canadian filmmaker James McSwain; rather than following the notion of ‘know thy self,’ Reinke stated that he prefers the maxim, “Use repression in a useful way.”

The material of cinema and performance was a crucial part of the various live events and exhibitions. Filmmaker and archivist Andrew Lampert’s series of ‘contracted cinema’ performances (as opposed to ‘expanded cinema’) were presented under the title ‘Celluloid is not Cinema.’ Taking the form of proposals, screen tests or talks, the three works he presented explored his own conflicted sense of self and his family history. Am I From Brooklyn? was made in response to being called an artist from Brooklyn (where he currently lives but which is a long way from St Louis, Missouri where he was born) and consists of a series of films exploring sites of his potential upbringing in three Brooklyn neighbourhoods. Accompanied by a prerecorded commentary (from a previous presentation for which the work was made), he tells stories about the locations of his invented childhood, reminiscing about everything from the quality his neighbourhood pizza palour and his time in the local bank. His other two works take the form of screen tests for an upcoming project exploring his Jewish background and his difficulty assimilating it into his contemporary identity, both developed through his collaboration with actress Caroline Golum. Rigmorale, Reversal features Caroline playing out a scene in a field from Andrew’s distant grandmother’s life, in which, while escaping the Pogroms, she loses her baby. The unedited footage is accompanied by a non-synch soundtrack of the actress delivering different versions of the soundtrack (which largely consists of hysterical wailing) which as well as becoming increasingly impassioned is also peppered with Caroline venting her out of character frustration with Andrew’s process and the absurdity of being asked to repeatedly deliver her voiceover onto Andy’s voice-mail.

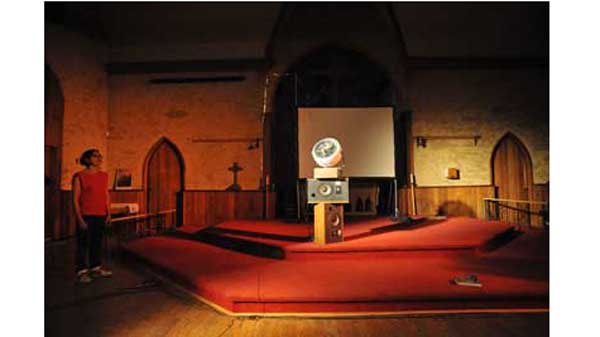

The work of Colombian artist Icaro Zorbar consists of intimate actions, or “assisted installations” as he calls them, using analogue equipment that last just a few minutes. These temporary sculptures, all delicately constructed and open to the dictates of chance, incorporate Walkmans, record players and music boxes in unusual configurations to play snippets of music, usually a Spanish language cover of a melancholy ballad. The piece Poco a Poco (Little by Little)Llegando a ti (Approaching You) by Pepe Aguilar, played with small delays by the needles of three turntables, as the gaps between the needles gets closer and closer it literally enacts the song’s lyrics: “Little by little, I am approaching you, I am approaching you.” His piece Ventilador (2007), performed in the Music Gallery venue, a Church which plays host to contemporary music converts, involves the magnetic tape from a cassette placed on the floor which is played through a walkman mounted on a fan. As the tape plays out Vincenzo Bellini’s “Dolente Immagine,” it is accompanied by the loose end of the magetic strip which is caught and flickers in the fan’s breeze.

Roman Signer’s exhibition Cinema at the Mercer Union Gallery, provided another reflection on what it is that makes up the cinema experience, consisting of a projection of Restenfilms /Film leftovers, an hour long video of outtakes from his many experiments and several rows of wooden chairs lined up to create a small improvised cinema. One of the chairs on the back row is attached by a rope to a machine which repeatedly pulls the chair back onto its hind legs and then lets it drop, creating an intermittent noise like an impatient spectator leaving the screening. This distracting presentation is perfect for his Restenfilms, which as well as various failed experiments and many false starts also includes images of the Swiss landscape in which they are staged. The distracting presentation and the many errors and mistakes in the video, make the work all the more suspenseful and intriguing; the more time I spent with it the closer I felt I was getting to the one perfect action or moment which never arrived.

The screening programme presented a broad international selection of work. As well as screenings dedicated to Canadian James MacSwain, there was John Gianvito’s acclaimed essay film Vapor Trail (Clark) on the legacy of US imperial presence in the Philippines and two programmes guest-curated by Jean-Marie Teno, Reframing Africa which attempted to counteract the “Afro-pessimist trend in major European film festivals” by presenting individual points of view from the last 30 years of African cinema. Two programmes dedicated to the recent exhibition and publication project Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Area featured many great works, including George Kuchar wonderful melodrama A Reason to Live, Lawrence Jordan’s brilliant city film Visions of a City (1957-78),one of his few non-animated works, and Anne McGuire’s sublime absurd-poetic video All Smiles and Sadness (1999). From the few film programmes I managed to see during my limited time in Toronto, Penumbra a beguiling film on language, and the fractured nature of family history by Columbian artist Kimberly Forero-Arnias was particularly striking. Combining subtle sound editing and the off-setting of speech and translation, through the insertion of subtitles in gaps between images, the film describes a complex story of the filmmaker’s aunt and her rejection from the family. As is stated in the film: “One person says one thing, another says something else and no one understands each other.”

Two films described monolithic landscapes both under different processes of construction, from the Italian marble quarry depicted in Anglaia Konrad’s austere Concrete & Samples III Carrara (Belgium, 2010) to the island in the middle of Lake Superior near the Canadian border, which is under the slow process of being turned into a nation park, depicted in Vera Brunner Sung’s Minong, I Slept (USA, 2010). Beautifully shot in silent 16mm film, both films describe forms and structures that have or are in the process of emerging from the natural world with markedly different inflections. The title of Vera’s film recasts the island as a dormant beast. The mythic quality of the name seems like something drawn from H.P. Lovecraft’s mythology, which the film subtly alludes too in its recording of the traces of former inhabitants and the slow processes of reclamation, in particular an idylic forest clearing which underneath the moss and vegetation disguises a field of discarded antlers and animal remains. Both films describes not natural idylls, or the scars left by mankind, but rather the living face of the earth in the post-industrial age.

The festival closed with Tod Browning’s silent film West of Zanzibar (1928), with live accompaniment by the Toronto based hardcore punk band Fucked Up. The film, an intense masculine melodrama, plays out its tale of bitter revenge in the ‘savage’ jungle of sub-tropical Africa, replete with black magic practicing natives and ivory dealing white colonialist. In this distant outcrop lives the bitter former magician Phroso, played with vicious zeal by Lon Chaney, who in the film’s opening is betrayed by his girl and crippled by her lover. In the midst of the jungle, ‘Dead Legs’, as his drunken cohorts call him, performs magic to entrance the natives and establish himself as a pseudo-King, as he plots his revenge on his former adversary Crane (Lionel Barrymore), whose daughter Phroso has secretly brought up in an African whorehouse. This incredibly bitter film found a fittingly stark and intense accompaniment in the driving rhythms and noise score of Fucked Up. Its tale of self-deception played out in the backdrop of the exploited African jungle can be read as a barbed attack on the hypocrisy of the colonial mindset. As Guy Maddin has declared: “This may be the meanest of films from those two meanies. The sometimes indifferent Browning really got up for this one.”

George Clark is a writer and curator based in Los Angeles