l arrived at Hatoum’s video work by chance and also strategically. My first encounter was with So Much I Want to Say (1983) and I came across it on my way to see the installation of John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation (2013) at Tate Britain.[1] I was finding my way to the Akomfrah film installation by way of a concept of articulation and a sense for the re-articulation of Hall in the work, by way of montage, by way of conjunctural analysis, and by way of its single-screen other The Stuart Hall Project (2013). My initial experience of Hatoum’s piece was formed in the proximity of the Akomfrah installation and ideas about the voice, subjectivity, diaspora, encounter, and difference. As I pursued this moment from a chance encounter to a deliberate engagement these ideas continued to percolate. Some of the reflections that filtered through have found their expression in the diptych portrait of So Much I Want to Say and the later Measures of Distance (1988) presented below.

Several years space the making of the two pieces, they work with different materials, and they come to their video form by different routes, but the two works still seem to me to be sutured together. Both having been produced in Vancouver at Western Front, they are also twinned as moments of a long relationship with the artist-led centre which began in 1983 when Hatoum joined it for an artist residency at the invitation of performance artists and two of the co-founders of the centre Kate Craig (who she worked with closely) and Eric Metcalfe.[2] Together the pieces precariously and provisionally bookend a period of rigorous engagement with video and performance and of working at Western Front.[3] What brings the two works together despite (or perhaps in and through their differences) is carefully pursued interests in subjectivity, affect, and language. At the of risk offering a closed story for what the works do, there is contextual information that I could and will go on to (ambivalently) reference. However, I think one of the most compelling things about the two works is their exploration of the limits and effects of expressivity, what it means to encounter that question in audio-visual culture, and specifically how that encounter can be staged in a time-based medium to host contradiction and possibility.

Studying Hatoum’s early video pieces is slippery work. It’s not just a resistance to static, linear narratives which makes me hesitate about how I frame the works, but a sense for the complex relation between performance and video that they negotiate. So Much I Want to Say is an excerpt of a recording of the event Wiencouver IV. This was the fourth event in a series of artist exchanges between Vienna and Vancouver organised by Robert Adrian (who was also an artist-in-residence at the centre at the time) and Hank Bull (an artist, curator, and organizer at the centre).[4] The event series which was attended by live audiences produced works that used a range of telecommunications technology including the slowscan video that Hatoum uses for her performance. So Much I Want to Say is then a recording of a transmission-based performance that preserves and re-produces some of the experience of receiving the mediated performance. The work we could say is an example of versioning. Other works by Hatoum made between 1980 and 1988 involve cameras in the performance (Look, No Body! 1980; Don’t Smile You’re On Camera 1981); offer a record of performances with live audiences (The Negotiating Table which was previously called Bars, Barbs and Borders 1983; Variations on Discord and Divisions 1984; and the video of the performance of Roadworks 1985); incorporate records of performance as part of its content (as in Changing Parts 1984 which draws on a video of the 1982 performance Under Siege and gains a new title); reference elements of a performance (as in Eyes Skinned 1988 which uses some of the props and costume pieces used in Variations on Discord and Divisions as well as its critique of news reporting, and use of projection); or offer a kind of slide-tape work (Measures of Distance). These categories seem porous, and the status of video appears changeable and unruly. Although a couple of the videos of performances do not seem to be making claims to autonomy, there is overall a sense that the use of video and audio-visual technology in Hatoum’s work developed in the exploration of a dynamic and complex relation to performance. Some of these ontological issues speak to questions of positionality, subjectivity, and technological mediation, the relation between the body and its representation, and the meeting of art and life that we can follow to the artist’s later practice. This range also references the highly varied terrain of experimental video work since its formative years in the late 60s, and the trans-disciplinary practices (including an overlap with performance) and theoretical interests that artists drew on. In an essay on video installation in continental Europe and North America, Chris Meigh-Andrews picks up on a number of recurrent strategies and interests which he tracks from the late 60s to the end of the 80s.[5] These included efforts to disrupt the passive viewing conditions of TV through performance and/or the use of projection and an exploration of the spatial presence of video installation and the active engagement of audiences by way of physical positionality it demands. While not setting out to offer a comprehensive account of video art during this period, Meigh-Andrews recognises the medium as a distinctly ‘international phenomenon’ and suggests that his survey should be placed in relation to studies of practices in the UK, Australia and Japan.[6] We can see these concerns along with an interest in the relation between the body and imaging technology and a notion of liveness that is reflected in Hatoum’s work in the 80s, despite the fact that she had connections to multiple places and worked between Canada and Britain. With regard to her positioning between these two places, some of Hatoum’s experimentations clearly place her in conversation with practitioners at Western Front (see for example, Craig’s Delicate Issue, 1979) while her interest in the political question of representation, the personal content of Measures of Distance, and her use of performance can be used to locate her within a new generation of British avant-garde filmmakers in the 80s. According to Michael O’Pray, this generation was characterised by a pluralism of aesthetic and political reference points, which challenged on its emergence the hegemony of formalism.[7] Within this context, the growth of black independent film is another significant movement that O’Pray also recognises. The main proponents here were collectives and workshops[8] whose growth was supported by the Greater London Council and the newly-established Channel 4 under the initiative of the 1982 Workshop Declaration.[9] The declaration itself was formed out of discussions between the Independent Filmmakers’ Association, the Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians, the British Film Institute and Channel 4.[10] Although ‘black’ in the 80s was mobilised as a political category and extended to a number of marginalised communities (Retake, for example, was a British-Asian collective), and many of the leading figures of the Workshops Movement came out of art schools, it’s not often that Hatoum is positioned in relation to this moment.[11] Hatoum did not belong to a workshop or to a large ethnic minority, but she was not unengaged in racial politics in Britain (see for example, Roadworks, 1985) and had a British passport since she was born..[12] Additionally, while the division between film and video (marked in many of the workshops’ names) was still present, it had, in part because of technological developments, begun to blur.[13] There are important differences between the output of these collectives (which itself was varied) and Hatoum’s work which, arguably, draws on a more ‘Structural/Materialist’ aesthetic as well as in the relative histories of migration and diasporic presence. While this is not an effort to identify Hatoum as a black British artist nor an argument for the continued relevance of the unity produced by the category, the lack of contact between the two in accounts of film and video is worth recognising.[14] Maybe it is, to an extent, a symptom of the disproportionate emphasis which has been placed by commentators on her Palestinian family and their history. Or perhaps it’s a response to the fact that she spent a significant amount of time in the 80s working in Canada.[15] Either way, this absence draws attention to additional possibilities for remapping Hatoum’s practice and engaging more deeply with her relatively underexplored body of video and performance work and its exploration of diaspora experience, subjectivity, and the question of representation.

This takes me back to the Tate exhibition where Hatoum sits with R.B. Kitaj, Sunil Gupta, Maud Sulter, and several other artists who are brought together over this ‘unfinished conversation’ on British identity and diasporic presence. These various positionings emphasise the narrativizing work that is part of art historical analysis and is expressed through frames of periodisation, medium, and nationality, as well as the various perspectives (e.g. feminist and post-colonial) that guide approaches. At the same time, each of these articulations involves a disarticulation and rephrases its object through a complex of historical, political, and aesthetic concerns. And just as these conceptual frames configure their object differently, linguistic descriptions, while not purporting to be a substitute for the work, fulfils more than an illustrative role. Here, in my text, description is taken up as a performance of criticality which allows me to sit with affect and make sense in the constellating movement between film and text, author and producer, self and other, inside and outside, and draw Hatoum’s two works together in plays of proximity and distance.

Part 1

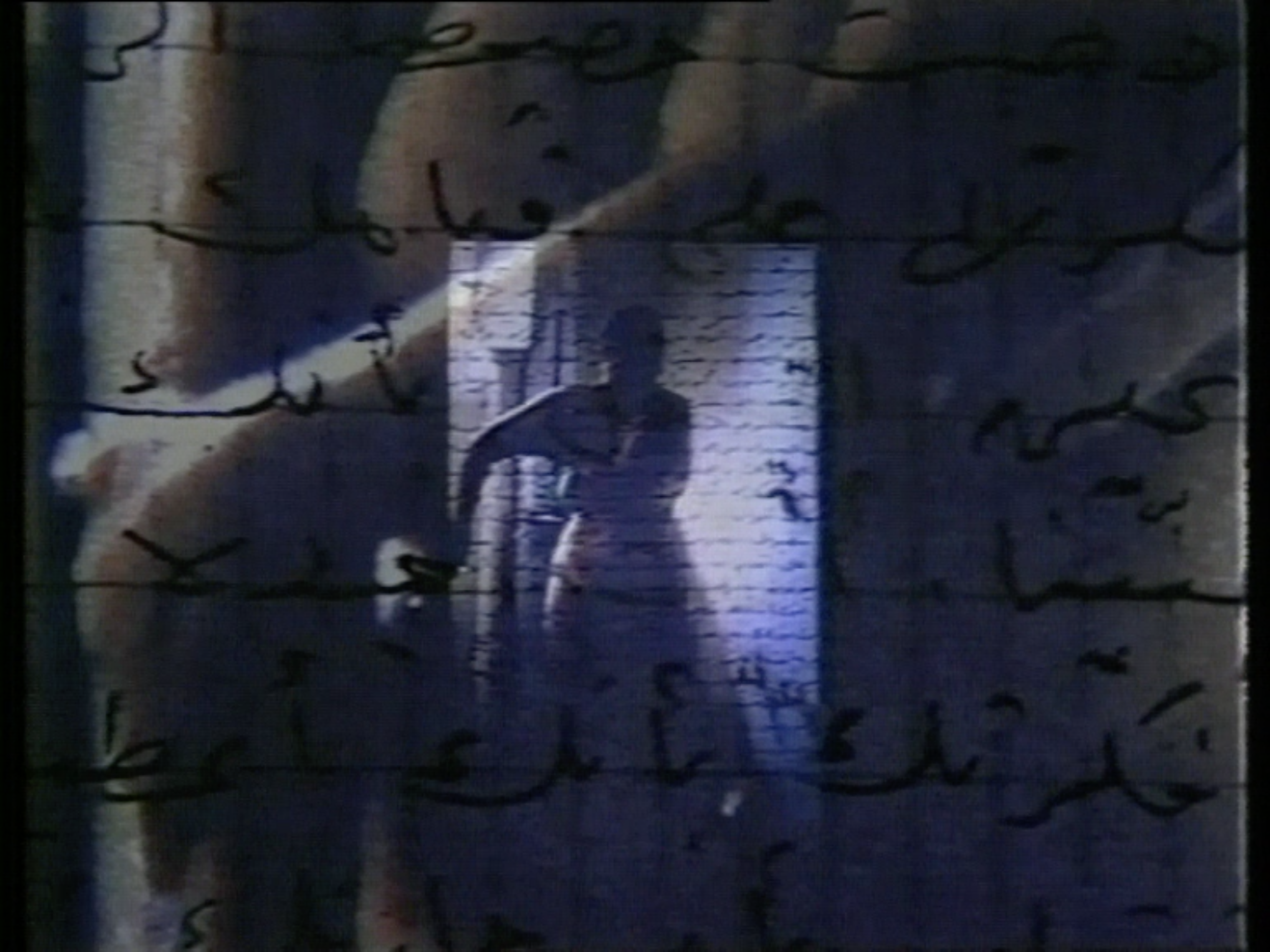

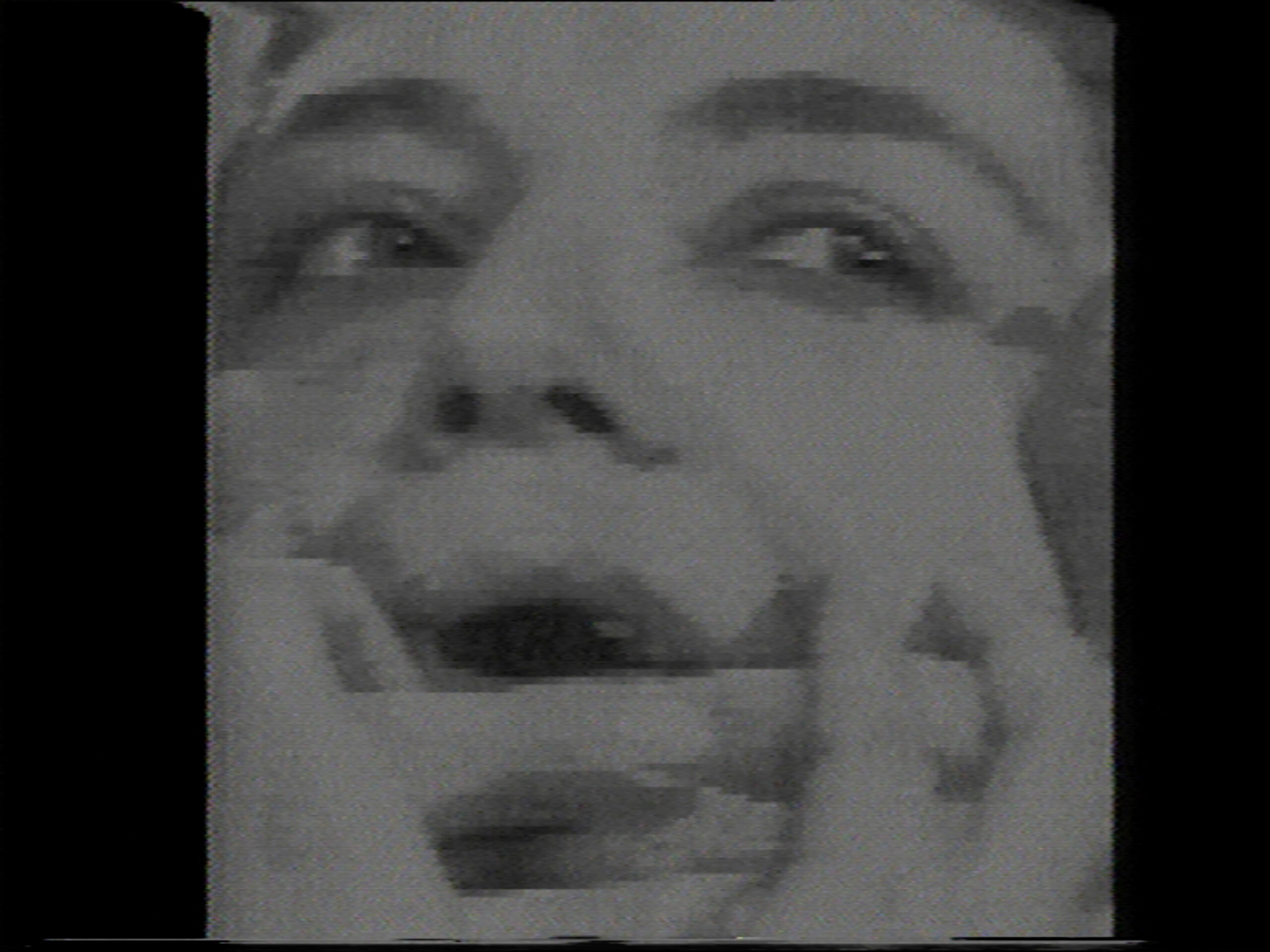

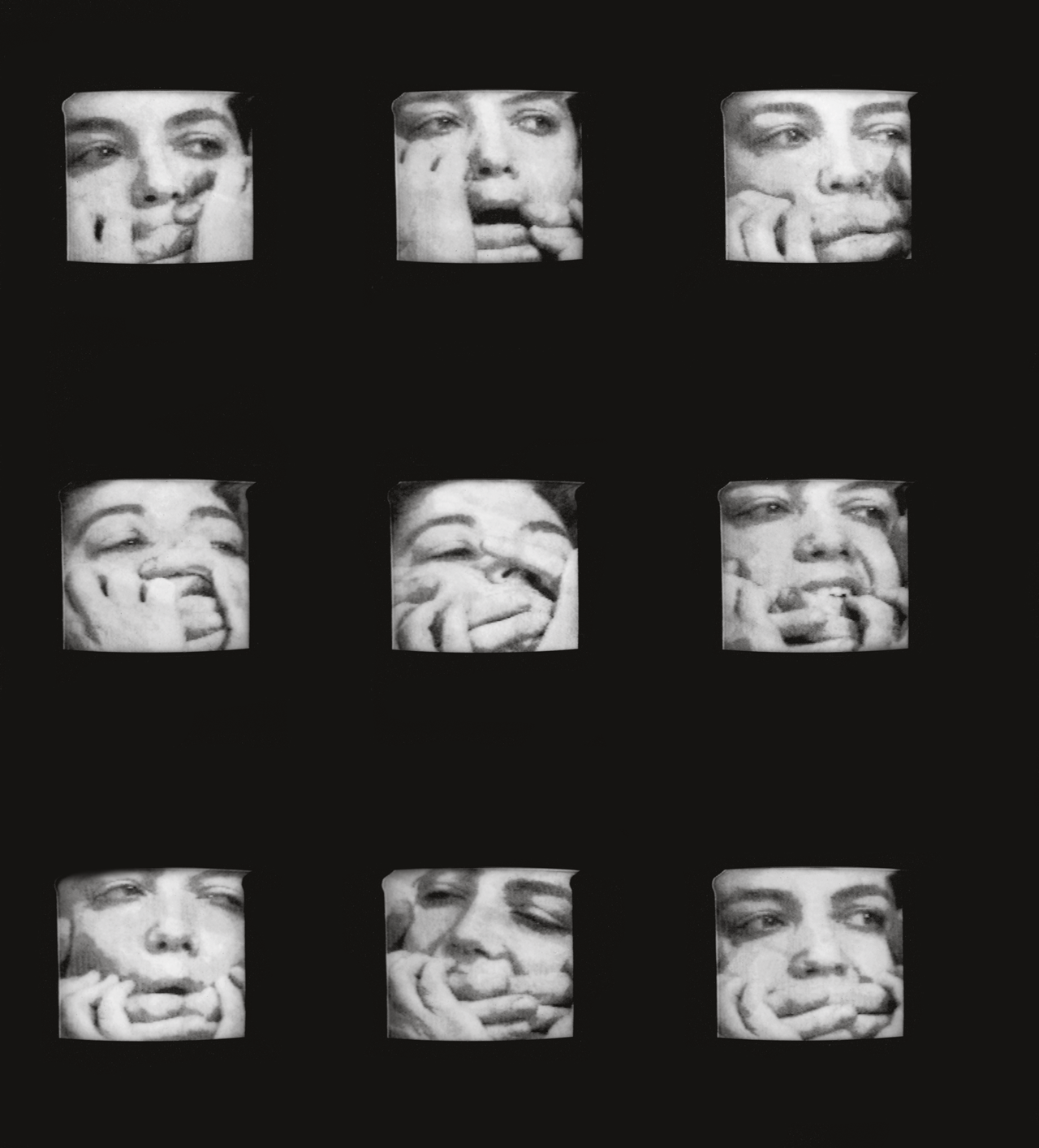

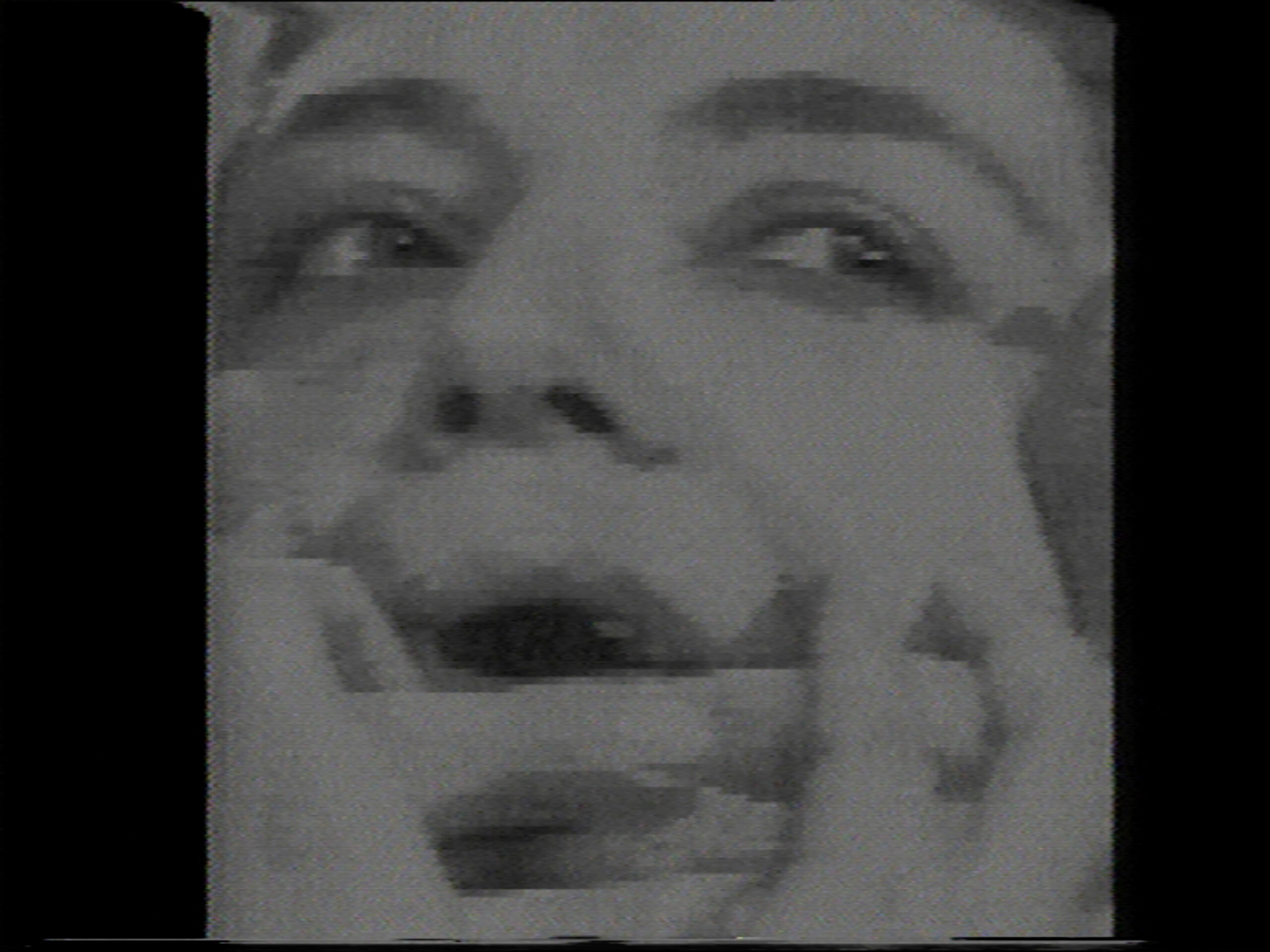

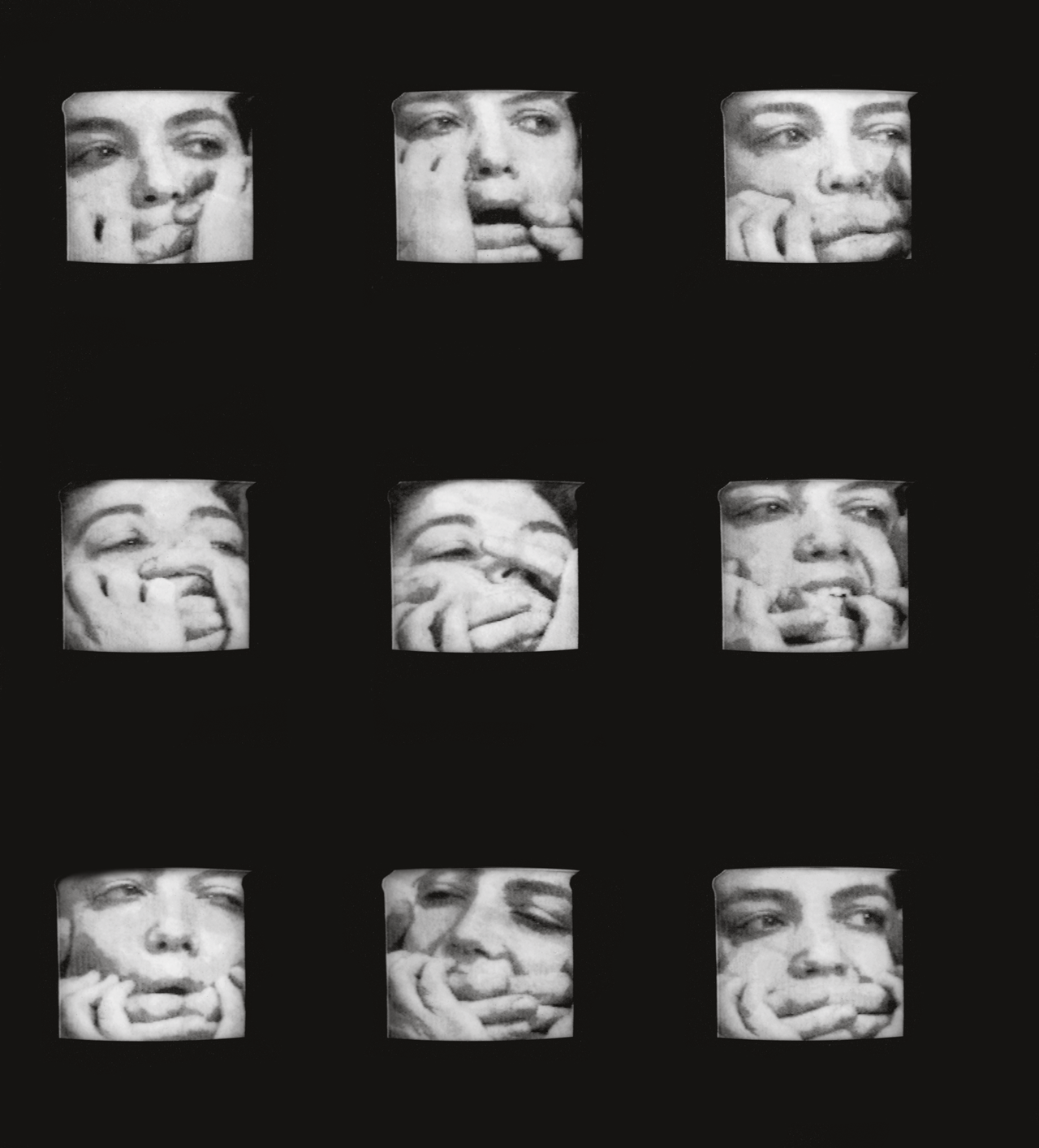

So Much I Want to Say is made up of a looped recording of Hatoum’s voice saying ‘so much I want to say’ combined with an unrehearsed performance of a set of poses involving Hatoum and Hank Bull. His are the hands we see in the video over Hatoum’s mouth clasping, covering, grabbed, and almost bitten. An edited recording of the activities of Wiencouver IV shows Hatoum facing a monitor which depicts the images that will be formed and guiding the hands into the positions they occupy. The poses we see are captured and then coded into electronic information to be carried along a telephone line and reformed as image on a monitor in Vienna (BLIX)—a transmission which lasted eight seconds. Sound is simultaneously transmitted along another line. The piece was spontaneously conceived during the event, and this detail, coupled with the fact that Hatoum faced and responded to two monitors during the performance (one showing the image just sent and the other connecting to the live camera operated by Kate Craig), describes a generative space between performance and transmission. This context doesn’t carry over into the video that is So Much I Want to Say, but the work’s reflexivity does correspond to it, and while amplifying the interest in active communication that characterised the event, as well as interests in medium specificity and process.

Having encountered the work before, I realised when I saw it again that I had misremembered each new image beginning where the artist’s mouth should be. I had misremembered it as some kind of reflexive refrain that emerged from and returned to a mostly-unseen, buccal cavity, and produced the artist in an endless efflux and reflux of sight and sound.[16] In actuality, the scanning motion begins (as one might expect) from the top with each image slowly forming as it replaces the one before. These images are the same: they show a cropped, close up of a gesture of violent silencing; the sight of Hatoum’s mouth being gagged by a pair of (male) hands. The images are also somewhat different: the face we see turns to different angles, there’s an attempt to bite the hands that gag, and at some point more of the face is covered. It’s not a continuous series that aims for an illusion of motion, but fragments of a struggle that takes place at a distance and is transmitted as the claustrophobic proximity of the close up. Each slow-moving image tails another; the closeness is unrelenting, and the artist’s face is presented to us an ongoing, unfolding surface that perpetually keeps the possibility of its depth to itself.

The work’s title references the statement that makes up its audio content: a Möbius strip of reflexivity which suggests that my memory lapse might not be insignificant. ‘So much I want to say’ is an everyday statement. It is commonplace and relatable, but it turns mutic and uncanny through repetition, technological mediation, and the violence depicted in the images in the work. The statement takes us inside the work to the inside of speaking while at once keeping us on its outside. Is it testing the possibilities for expression outside of spoken and written language, and presenting, as Gannit Ankori suggests) as a kind of body language?[17] Or does it articulate a languaged and mechanically mediated body? If it deals with a body language it’s one that troubles im-mediacy and queries itself and the too many utopian hopes for technological development that are entangled in it. The lags and disconnections, as Bridget Crone notes in a lecture on Hatoum’s video works, register the gaps between here and elsewhere, and can also speak to the unevenness of access and experiences of technology in temporal terms and (we might add) to the geopolitical limits of the communication arts.[18] These concerns with access are also raised in the publication Arts + Telecommunication put together by Robert Adrian and Heidi Grundmann following Wiencouver IV which documents the exchanges that took place between 1979 and 1983. Included in the book is a piece by Adrian in which he describes the necessity for telecommunication works to have a global reach, so as to be truly communicative and play a political role in challenging power relations and hierarchies. Without this global scope and the equality of access, the content of these works, he argues, is almost irrelevant.[19] An interview with Tom Sherman in the book develops an understanding of this context and discusses the infrastructure needed for access to equipment and resources, noting the relatively high support for new media in Canada at the time.[20] Conditions speak and a sense for this informs and mobilises a number of reflexive video practices (including So Much I Want to Say) which work with media specificity, raising challenges to a medium through that very same medium to stage an immanent critique.

So much I want to say, Mona Hatoum, 1983

The repeated statement about speaking in So Much I Want to Say constitutes speech and measures the limits of a speaking, hearing, and seeing the subject against itself. Said once it could present a desire for expression: a temporarily perplexed but fulfillable potential. Uttered again and again and again in the present tense it collapses that (virtual) trajectory into an incantatory, iterative loop. The statement’s presence is formed by the absence of speech and describes a condition of (im)possibility: it constantly vanishes into itself even as it makes a statement and bridges the distance between Vancouver and Vienna. It has everything to do with the politics of representation or who can speak, what they can say, and whether they are heard, while at the same time having everything to do with tracing a process of becoming.

Here I think it’s useful to not immediately think of auto-biography but of the critical concept of diaspora. Although the notion of diaspora seems to invite reference to Hatoum’s biography, invoking it is not about instigating a bio-contextual reading that tries to contain meaning or defer analysis. It is also not about forgetting or eliding over biographical detail — a move that would restrict engagement and run the risk of being seen to flatten specificity in order to make the works more widely consumable.[21] As Hatoum herself notes in the often-cited interview with Janine Antoni in BOMB Magazine, part of the problem is that accounts of her work which frame in terms of her family history contain inconsistencies, and distort her work by emphasising some aspects of her life over others. Drawing on the diaspora as a critical concept is part of an effort to recognize the ways in which concerns with liminality, dislocation, and displacement that are often part of the experience of diasporic peoples find aesthetic expressions. It’s also about attending to the knowledge that inquiries organised by the concept can produce about subjectivity, representation, and history. Hatoum’s video and performance works are often (by her own description) ‘issue-based’, attending to a range of political issues from the civil war in Beirut and oppression of the Palestinian people to feminism, surveillance, and the (racialised) experience of urban spaces in the West..[22] These political issues are necessarily also aesthetic concerns and are enmeshed in Hatoum’s practice with a sense for materials. In her earlier works this is evoked in part by a reflexive relation to video/slide-tape/slowscan where we can see an effort to engage with the specificity of a medium and to draw us as audience members/viewers into this process. Thinking about the performance of the piece might bring us to think about the limits of international communication and movement, and the more specific restrictions on Hatoum’s ability to contact family in Beirut, as well as the restrictions on movement that are historically part of her and her family’s experience. In the context of these political restraints, the disjuncture of the transmitted slow scan images can may correspond to existential states displacement, dislocation, and exile. The expression of unspeakability that is ‘so much I want to say’ and its repetition comes to signify a traumatic absence more clearly, and becoming recognisable as an unstable referent for an unspeakable violence or the violence, the violence of speech repressed, or both.

Stills from ”So much I want to say”, 1983. Black and white video with sound, 4 min 41 sek, © Mona Hatoum. Courtesy the artist.

The use of the artist’s face is not a confessional gesture; it’s not about consolidating meaning with a return to a living person, or about turning to the body as a site of authenticity, but rather about using the body of the performer to work something out through action and, in this case, working something out specifically through mediated action. The work presents both the specific body of the artist and a general body that indexes sociality and embodied experience. Several descriptions of the work (including this one) note that the hands we see around the face of the artist who is a woman are male — a description which, arguably, implies that the images of gagging are depictions of gendered violence. Given that the work was composed spontaneously and in response to an event in progress the decision to include Bull in the performance would have been a quick one. Saying that, the fact that Hatoum was significantly influenced by and involved in a particular moment of feminism, while also invested in racial politics, is not irrelevant to a reflection on intentionality. In this context, the fact that the other performer (Bull) is not just a man, but a white man could make the interpretation of the gagging as both gendered and racialised equally available. Within these analytical possibilities there’s a kind of play between the politics of representation and the representation of politics in which the artist is implicated and evoked through the use of her face and voice. The quality of the black and white slowscan images denies a stable sense of how race and gender are expressed in the work, prompting us to turn to Hatoum’s person (to the knowledge that she is an Arab woman) to support a reading of the political affects of the work. At the same time we are brought by the work’s strategies of intensive self-referentiality to encounter the artist not as a person but as effect. An alternative to a reading which may seem problematically imply essentialism (in terms of race/gender) is one which responds to these same details by recognising the articulation of difference in the work and the significance of difference for its exploration of subjectivity. There is a productive tension that is produced by approaching the work through a post-colonial, feminist perspective, and by attending to questions of race, sexuality, gender, and sex which are raised by the visibility and audibility of its enunciating subject. This is the crux of the work’s political affects, raising multiple concerns with the body and the fields of its expressivity form that mark important points of contact across Hatoum’s career, while forming hinges that allow us to swing now to the other half of the diptych.

Part 2

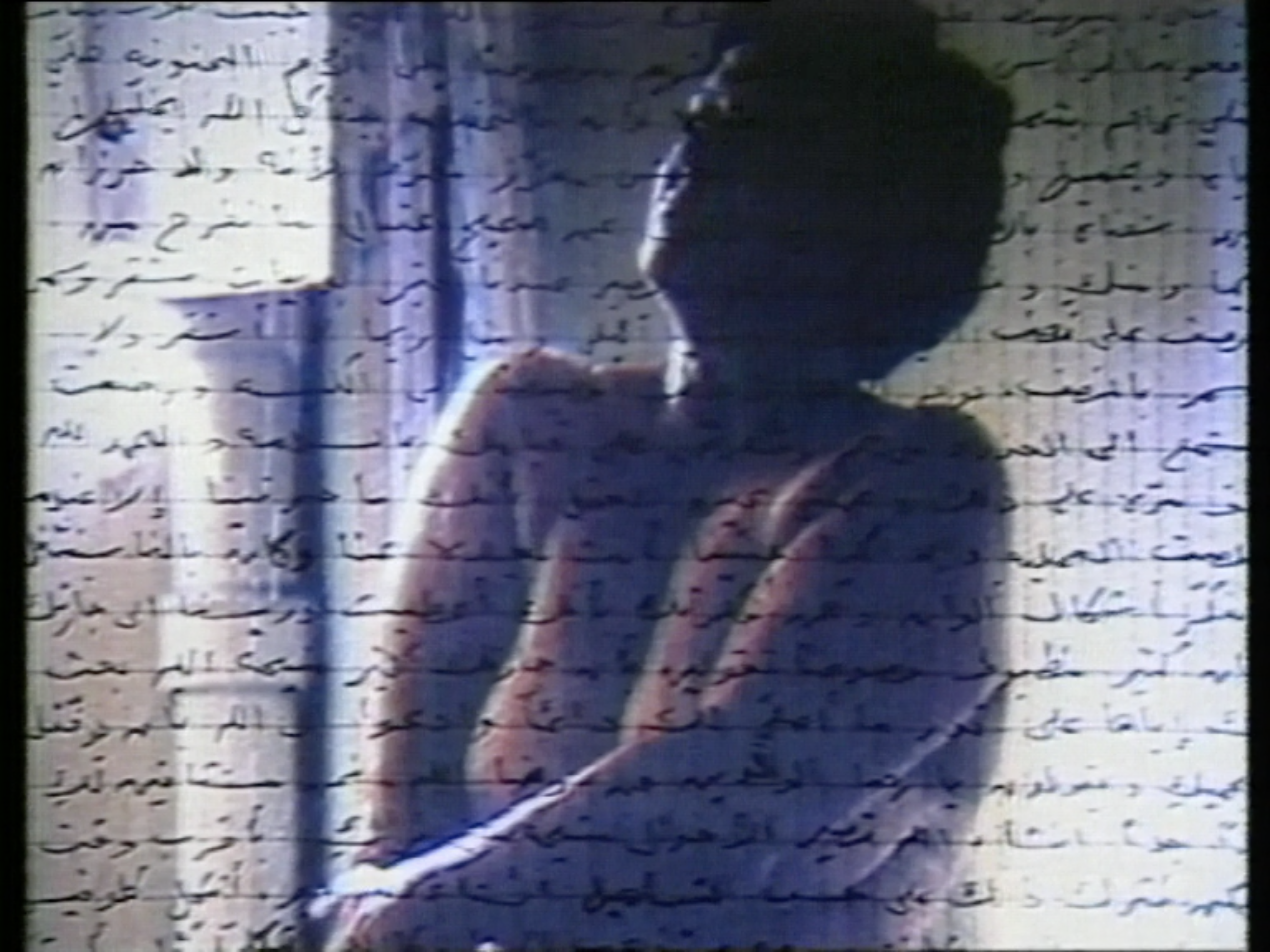

Measures of Distance, Mona Hatoum, 1988

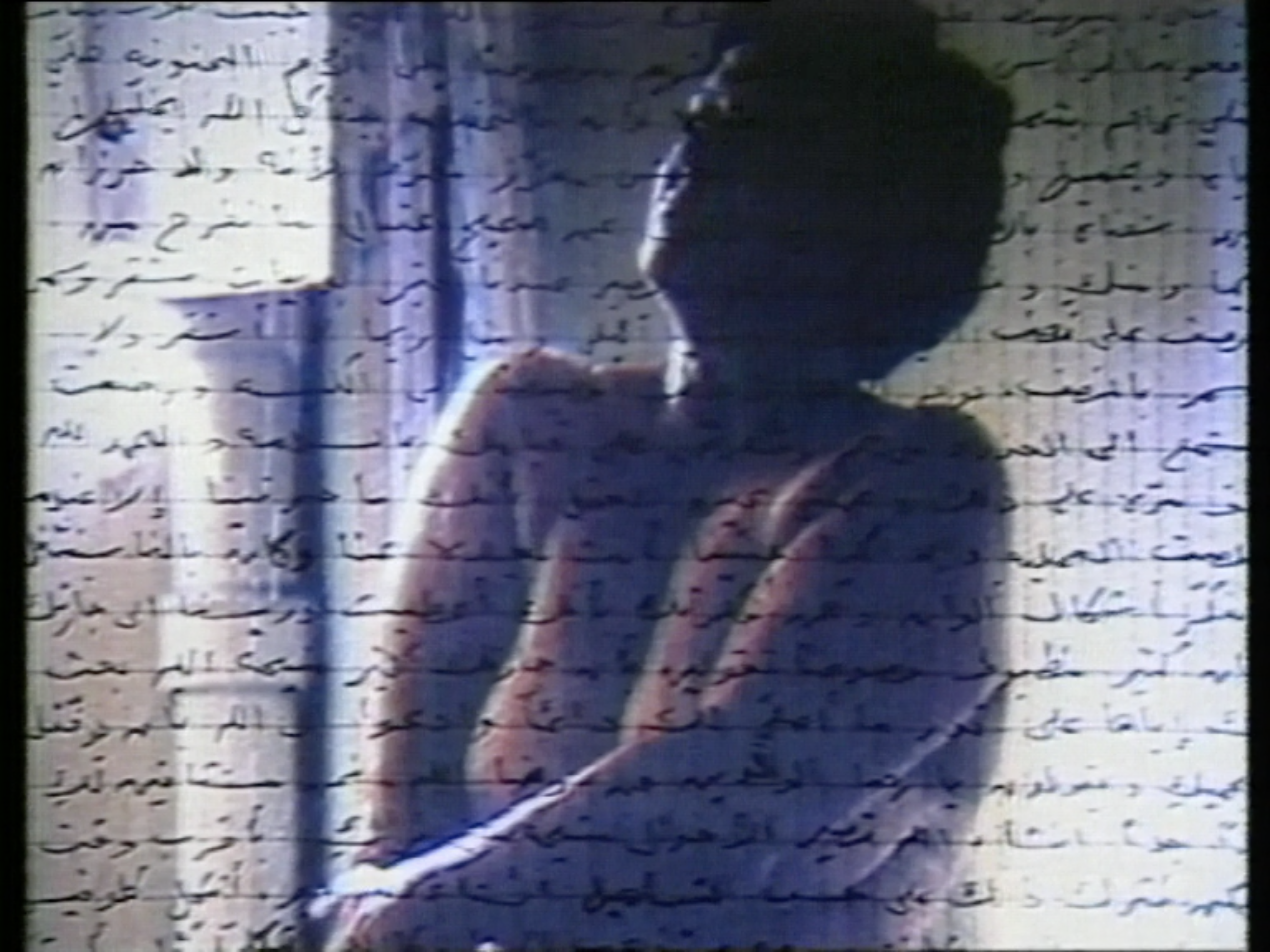

Measures of Distance begins in the middle and with laughter. We find ourselves joining an audible, ongoing conversation conducted in Arabic between Hatoum and her mother. The audio recording of the conversation does not correspond to the visual content of the piece which is formed of a series of images that gradually become more clearly identifiable as images of a female nude. We are positioned outside of the conversation. These images, we learn, are photographs of Hatoum’s mother taken in the bathroom of the family home. They are grainy, with finer details like her mother’s face not really visible; sometimes we realise that what seem like abstract forms are enlargements of parts of the images. Printed onto slides and translated into video they are not digital and cannot be termed ‘poor images’ in Hito Steyerl’s sense yet they are incomplete, and errant in their own way.[23] For Gabriella A. Hezekiah this quality does not signify a poverty, lack, or absence, but rather an excess of presence and feeling. Hezekiah reads these images experientially as examples of a ‘saturated phenomenon’: objects that have such affective power that they thwart conceptualisation.[24] Instead, referencing Laura Marks, she says that we encounter them by way of a ‘haptic visuality’, and by way of a kind of perceiving that summons associations to touch and suggests texture and a particular kind of nearness.[25] The fuzziness and cropping of the images, combined with the fact that the photos are taken in the bathroom of the family home and the poses are casual, creates an atmosphere of intimacy. The images bring us close even as they deny us direct exposure, swerve away from the access demanded by a voyeuristic and objectifying gaze, and place the images’ iconic status under erasure.

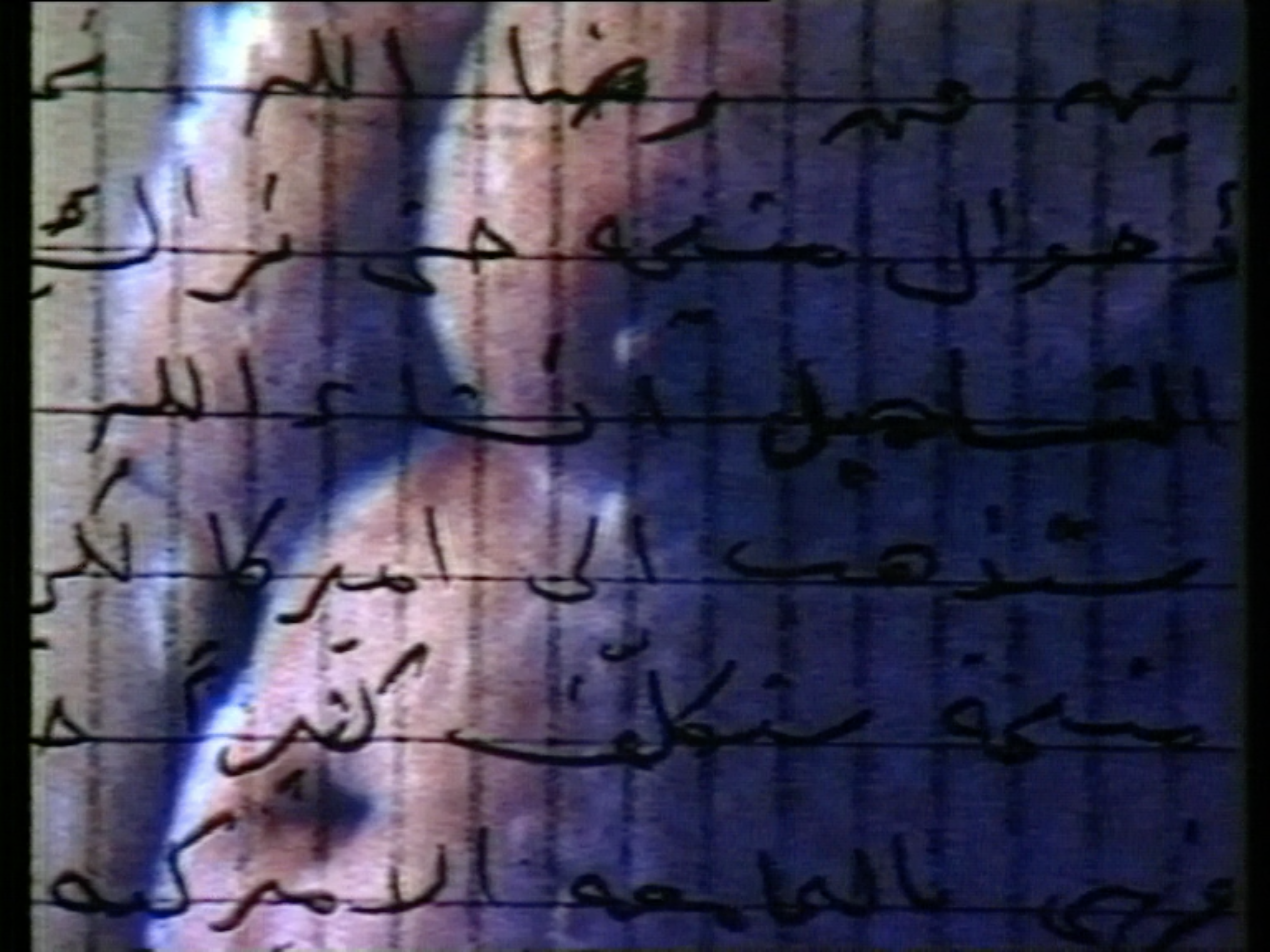

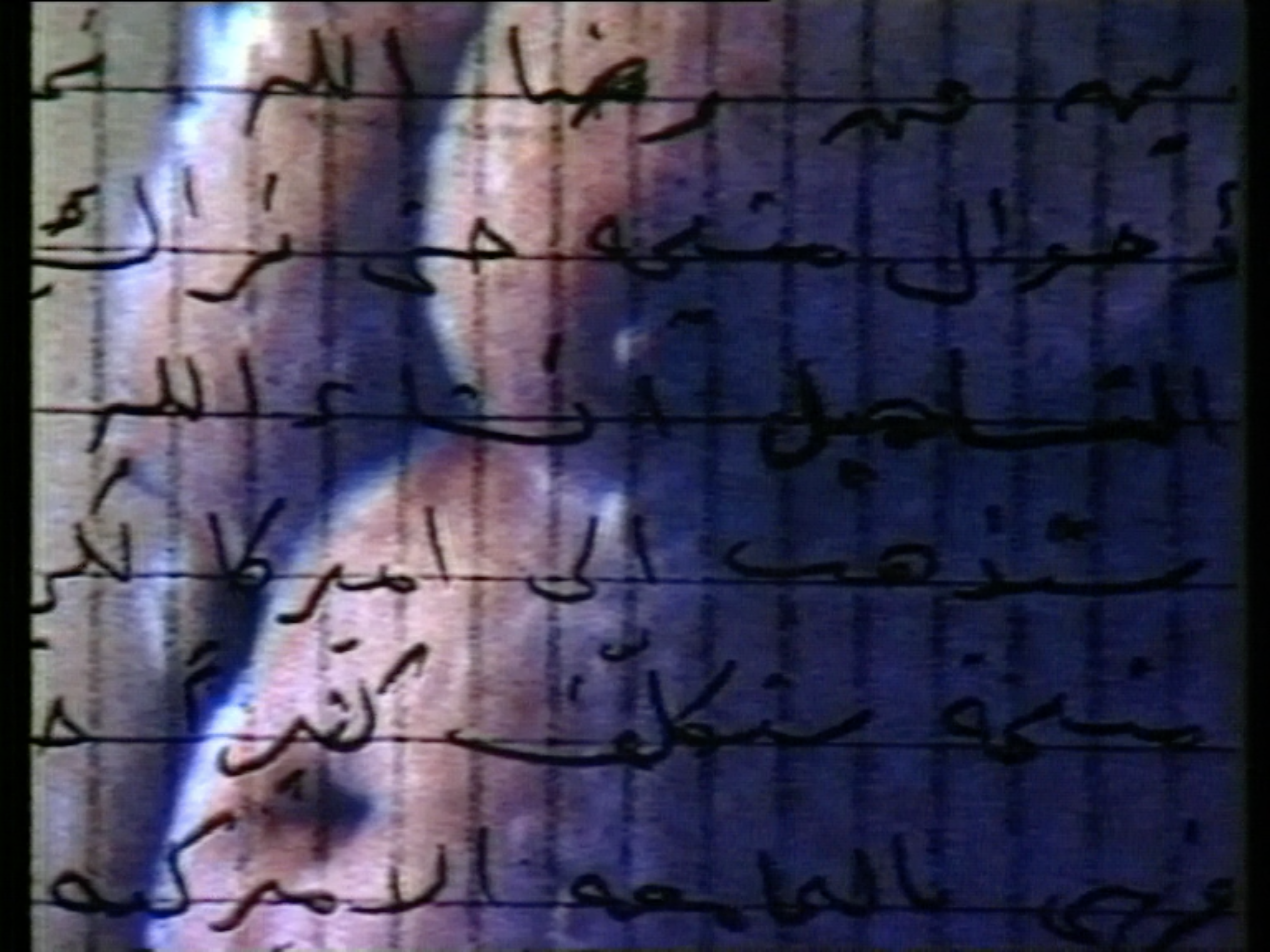

These images slowly fade out to replace each other and are always overlayed with enlarged, cropped sections of letters, written to Hatoum by her mother so that we see the images of text and those of the mother through each other as in a palimpsestic mode. Running horizontally across the mother’s body, the script and the quality of the lined paper form a grid-like texture that suggestively brings together the recorded conversation, the images, and Hatoum’s voice as different strands of a woven fabric. Surfaces of image, body, and text are brought together to articulate a kind of textuality in which mother and daughter interpolate. A minute into the work we begin to hear the artist’s voice. The translated address, ‘My Dear Mona’, opens her speech, identifying it as the text of an epistolary exchange with her as its recipient. As the work progresses, the repetition of the address segments the time of Hatoum’s speech according to the content of five letters. Seeming to respond in part to the Hatoum’s unvoiced end of the correspondence, the letters speak of the experience of leaving Palestine, dispossession, grief at separation/s, the pleasure of having the recorded conversations and of taking the photos together, the father’s discovery of the artist and her mother taking photos, and his enduring resentment of the relation he felt excluded from. Reporting to her daughter on the father’s response Hatoum’s mother says, ‘it is as if I had given something that belonged to him’. The father’s introduction into the film through his envy unveils the sexual politics of the home and the renegotiation of identifications in the family as Hatoum becomes closer to her mother, emphasising the feminine intimacy of this relation between the two adult women. The recorded conversation between Hatoum and her mother that we hear at the beginning of the video continues throughout and is washed over by the sound of Hatoum’s voice in English. In the gaps of these readings it is possible to hear fragments of the conversation between Hatoum and her mother. The conversation (for those who can tune in to it) is expansive, addressing the mother’s youth, her experiences of going out dancing and its associated social codes, marriage and sex education, her honeymoon, pregnancy, female sexual pleasure, menopause, sexual desire…In the background we hear the sound of traffic coming through an open window.

Nothing in the Arabic conversation undercuts the content of the translated letters, although it does not simply repeat it. Often offering more intimate detail, the conversation is a supplement to the audio of the translated texts. We are presented with a change in the visual composition about halfway in, and again towards the end of the film. The first change is marked by a more distanced presentation of the overlapping images of Hatoum’s mother and her written letters. In this distanced perspective, the individual words of the text appear smaller, and we see something closer to a full body representation of Hatoum’s mother, though the details are still obscured. The second change is marked by the placement of an image of Hatoum’s mother (still overlayed with text, but now smaller) in the centre of a black frame. This black space behind the image is then replaced by another larger set of mother/text images. The content is doubled and divided into foreground and background which move to displace each other repeatedly, with the background occasionally darkening to black. The movement does not so much produce a sense of depth as a heightened awareness of the projection, illumination, and display of the images. Eventually, all the images fade to into a completely black frame while the translation of the letters voiced by Hatoum spills over beyond the display of images of Hatoum’s mother and past the visual end of the film. This darkness near the end of the film coincides with the report contained in the last letter (sent to Hatoum via her cousin) of the local post office being destroyed in an explosion caused by a car bomb and the lack of other reliable means of contact.

‘I felt we were like sisters, close together, and with nothing to hide from each other’

In Measures of Distance, the young artist is clearly in a position relative of power: she has control of the photos, the audio recording of the conversation, and the English version of the text. Yet, the permission to use this content, as we learn from the letters, is freely given as a gift and Hatoum’s voice, while performing as a mediating presence, is not the voice of an unimplicated cipher. In the (accented) English reading which Hatoum presents to us we don’t hear her end of the correspondence; nevertheless, the fact that she translates it and gives voice to her mother’s letters inserts her into it and presents it as an act of co-production. Through the reconfiguration and combination of the photos, the conversation, and the letters, the work produces an intersubjective, generative space, and offers a structured attempt to articulate these traces. In one of the letters, we hear Hatoum’s mother encouraging her daughter to go back to Beirut saying, ‘why don’t you come back and live here and we can make all the tapes and photographs you want’. This translation of deep longing, loosely parcelled up as a casual offer imparts to us the pain of separation and the burden of being the one who has left home, while also evoking a trace of the affirming feminine joy that having the conversations and taking the photos created. In another one of the letters Hatoum’s mother says that she enjoys answering her daughter’s questions, that despite their being ‘weird and probing’ they make her think about herself in a way she hasn’t before.

Measures of Distance, Mona Hatoum, 1988

Measures of Distance speaks of a plurality of measures and to an underdetermined notion of space. There isn’t one unit that can account for the different kinds of contact and separation, distance and proximity, and there isn’t a standard to measure against because the reference points are multiple, polyvocal. The reading of the translated letters gives expression to a self, divided and communicated to us as such in language and in the feminine space of the relation between mother and daughter. Their physical separation brings about the written correspondence which attempts to bridge the distance in the absence of other viable means for contact. Meanwhile, this dislocation is also registered in the necessity for translation, which indexes Hatoum’s Anglophone living and working conditions.[26] We’re not told whether her mother speaks English, but we do know that a work about their relationship can only be shared widely in translation. The final letter begins with the usual address, ‘My Dear Mona…’, but in place of the usual endearments, textured by untranslatability, we hear the words, ‘et cetera, et cetera’. In the context of the affectionate letters, the pain at separation they often express, and the sudden block in the channels of communication which the letter goes on to announce, the wearily repeated adverb subtly marks the presence of the translator/speaker, briefly, but clearly displacing the mother’s text with a modification. It reminds us that these letters are being re-presented to us and by the copresence of different temporalities in the film, but it also emphasises the task of generating a presence through these different fragments and the difficulty of sustaining it. Listening to the Arabic and the English at the same time requires a kind of oscillation or hovering, which is not entirely successful. The English translation sounds louder, and clearer, and is the dominant voice in part because we are positioned as its addressee, and the conversation in Arabic is often something we have to strain to hear, something that perhaps we need to overhear. This condition doesn’t describe a fetishized otherness but something expressive beyond its semantic value. Towards the end of the film, it’s possible to pick up on the repetition of segments of the audio recording. The repetition interrupts the illusion of liveness that the conversation produces, emphasising instead the status of the audio as mediated recording and the quality of the sound of the voices over the linguistic content of the speech.[27] Repetition is possibly chosen over silence, taking up the chance that playback offers for producing and maintaining presence, and deferring an end.

The audio recording of the Arabic conversation is layered through the read translations and offers an elliptical presence, that even an Arabic speaker — specifically this Arabic speaker — cannot fully grasp. The description of myself as an Arabic speaker is deliberate: I learnt Iraqi-Arabic before English, and before my parents moved from Iraq to the UK when I was around four. I learnt Arabic orally and developed my use of it in the hyperlocal environments of the family home, other family homes, Saturday schools, and mosques. Traces of these people, places and times are carried in my speech, and in em-passioned silences: there are some things that in Arabic are yet-to-be-spoken by me. Although I’ve lived abroad with my family in an Arabic country, I went to an international school while we lived there and was educated according to a British curriculum. I can read and write in what’s called modern standard Arabic but my proficiency is mismatched with my age and I’m sometimes shown up by chance encounters with small notes my mother has left lying around: neat but hand-written, her notes gibingly present themselves as incompletely legible scrawl. I love being bilingual, but expressions like ‘mother tongue’, ‘first language’ and ‘native speaker’ feel de-natured, or like everyday objects that turn out to be surprisingly weighty in the wrong places, things that might, if handled casually, make me lose my balance. Although one auto-biographical work doesn’t necessarily demand another, it’s worth noting that there’s an aspect of the work that is only made available to a bilingual/multilingual audience. What I’m describing is not the same history or experience of migration but it finds expression in some of the same motifs of disjuncture and duality that are expressed in the piece in part through language. My partial contact with the work registers these differences in dialect and history, and simultaneously articulates other, alternate diasporic positionalities. Referencing my own history offers another way of unearthing the fragmentary, interstitial structuration of the work, and the possibilities that its reflection on difference offers for ‘inscriptions of many forms of difference’.[28] Given my relation to Arabic, it is also, to some extent, auto-biography as disclaimer.

To bring my reflections on Hatoum’s two works to some form of closure I’m going to turn to two essays by Griselda Pollock both of which engage with Measures of Distance and place the film in conjuncture with two others: Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990) and Martina Attille’s Dreaming Rivers (1988). In one essay these three works are brought together in a radical, imaginary exhibition that forms part of the project of the virtual feminist museum. This exhibition is framed by the concept of a (belated) moment of the feminist avant-garde in the 70s and the critical possibilities for thinking about culture, history, and modernity it opens up by working with a maternal-feminine, and ‘in, of and from the feminine’. This theorisation of the maternal-feminine comes out of an engagement with Julia Kristeva and is not to be confused with literal motherhood, but rather constitutes the ‘imaginative and metaphorical site of notions of the creative, the generative, of becoming and of difference’.[29] Le feminin here is what is in excess of patriarchal order, and a ‘psycholinguistic and sociohistorical knot still to be deciphered and spoken’.[30] The interventions identified with this moment are characterised in part by an elliptical quality and form themselves in opposition to particular kinds of iconism and a phallocentric symbolic order. In the second essay, these same three films are brought together to think about how they stage what Pollock describes as ‘migratory settings’.[31] This is the movement linked to different forms of relocation and of time-based media which are brought to intersect in the enunciating subject in the three films. The psychoanalytical frame for this theorisation draws on the thoughts of Julia Kristeva, Christopher Bollas, and Bracha Ettinger on archaic subject formation and the interest in the maternal-infant relation (at least in the case of the first two). The discussion is involved and complex, but what I want to bring to bear on my reflections here specifically is the importance given to sound, affect, and a notion of resonance. The concept of resonance in the essay describes a theory of subject formation by way of co-affection and co-emergence which Pollock draws from Ettinger. Resonance also describes the affective atmospheres created by art, dance, music, and poetry — aesthetic practices which move us and draw us into transformative encounters, and make meaning in ways that ‘go beyond words’.[32] In her reading of Measures of Distance in this essay Pollock attends to the ambient quality of the Arabic conversation, placing its operation on an affective, non-verbal level. These words intersect with the carefully enunciated, ‘Arabic-inflected’ letters which produce ‘the acoustic echo of their repetition in the body of the daughter as she reads them’ to create a presence of severality.[33] The movement between these soundtracks and the different images works to imaginatively construct the mother-daughter relation as a ‘sonorous space’ of longing, affirmation, and ‘an instant of home-coming’. [34]

Although it does not deal explicitly with diasporic experience, So Much I Want to Say does, as I have shown, think through some of same questions of subject becoming and presence also by way of an enunciating subject. Here the meaning of the spoken expression changes with its repetition in time, and we recognise it as an utterance. Although the meaning of the spoken expression does relate to its semantic content, the meaning it communicates in repetition (as well as in conjunction with the images) exceeds that of the individual words or their combination.

Even taking into consideration the additional access that understanding Arabic grants, it’s clear that my readings (certainly my reading of Measures of Distance and less directly that of So Much I Want to Say) entwine themselves with the ideas and approaches in Pollock’s aforementioned essays. I’ve been reluctant to disentangle them because they have informed my thinking and rethinking and this relationship and the perspectives I draw on speak additionally to my own situation, to my education at Leeds, and my experience of having been taught by Griselda. In the intersections, there’s a sense of intertextuality, by which I make an effort to locate myself in relation to these essays; there is also a suggestion that education and practices of analysis be perceived as the products of articulations and within ongoing conversations. One hope is that in positioning myself in proximity to these two essays (as well as to the concepts of articulation and conjuncture on which I’ve drawn) my response to Hatoum’s work will be received as neither entirely original nor derivative but as an echo.

[1] Both works are currently on show as part of the exhibition Sixty Years: the Unfinished Conversation.

[2] ‘Variations on Discord and Divisions’, <https://legacywebsite.front.bc.ca/events/variations-on-discords-and-divisions/> [accessed 31 August 2022].

[3] Kristen Hutchinson, ‘Intimacy and Distance: Mona Hatoum at the Western Front’, Luma Quarterly (2020), <https://lumaquarterly.com/issues/volume-five/019-winter/intimacy-and-distance-mona-hatoum-at-the-western-front/> [accessed 31 August 2022].

[4] My research on Hatoum’s video works and So Much I Want to Say in particular would not have been possible without the generous help of Hank Bull and Western Front who were encouraging and happy to answer my questions and requests for resources.

[5] Chris Meigh-Andrews, ‘Video Installation in Europe and North America: The Expansion and Exploration of Electronic and Televisual Language 1969-89’, Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film, ed. by A.L. Rees, Duncan White, and David Curtis (London: Tate Publishing, 2011), pp. 125-37 (p. 126).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Michael O’Pray, ‘Moving On: British Avant-Garde Film in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s’, (2017), <https://lux.org.uk/moving-on-michael-opray-2002/> [accessed 31 August 2022].

[8] These include the Black Audio Film Collective (of which Akomfrah was a founding member) Sankofa Film and Video, Ceddo, and Retake Film & Video Collective.

[9] Tom Roberts, ‘The Actt Workshop Decaration Provides Financial Security and New Audiences for Independent Film and Video Workshops’, <https://www.luxonline.org.uk/histories/1980-1989/actt_declaration.html> [accessed 31 August 2022].

[10] O’Pray, ‘Moving On: British Avant-Garde Film in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s’.

[11] One exception being Griselda Pollock’s move to place Sankofa’s Dreaming Rivers (dir. Martina Attille, 1988) in conversation with Hatoum’s Measures of Distance and Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: a rural tragedy 1990). See Griselda Pollock, ‘Moments and Temporalities of the Avant-Garde “in, of, and from the Feminine”‘, New Literary History, 41. 4 (2010), pp. 795-820.

[12] Janine Antoni and Mona Hatoum, ‘Mona Hatoum by Janine Antoni’, BOMB Magazine, (1998), <https://bombmagazine.org/articles/mona-hatoum/>.

[13] Meigh-Andrews, ‘Video Installation in Europe and North America: The Expansion and Exploration of Electronic and Televisual Language 1969-89’, p. 135.

[14] O’Pray, ‘Moving On: British Avant-Garde Film in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s’.

[15] Antoni and Hatoum, ‘Mona Hatoum by Janine Antoni’.

[16] Or perhaps a haunting from the future, summoning installation works Corps étranger (1994) and Deep Throat (1996).

[17] Bridget Crone, Bodily States of the Image: Proximity and Distance in the Performance and Video Work of Mona Hatoum, online video recording, YouTube, 16 June 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cKe3ge_QY00&ab_channel=thisistomorrow> [accessed 16 June 2016].

[18] Crone, Bodily States of the Image: Proximity and Distance in the Performance and Video Work of Mona Hatoum.

[19] Robert Adrian, ‘Communicating’, Art + Telecommunications, ed. by Robert Adrian and Heidi Grundmann (Vancouver: Western Front Publication; Vienna: BLIX, 1984), pp. 76-81

[20] Tom Sherman, ‘Excerpts from an interview: telecommunications and art subsidy’, in Art + Telecommunications, ed. by Adrian and Grundmann, pp. 68-75.

[21] Mona Hatoum was born in Lebanon to a Palestinian family that lived in exile in Lebanon and had become naturalized British. See Antoni and Hatoum, ‘Mona Hatoum by Janine Antoni’.

[22] Antoni and Hatoum, ‘Mona Hatoum by Janine Antoni’.

[23] Hito Steyerl, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, (2009), <https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/> [accessed 10 October 2022].

[24] Gabrielle A. Hezekiah, ‘Intuition and Excess: Mona Hatoum’s Measures of Distance and the Saturated Phenomenon’, Paragraph (Modern Critical Theory Group), 43. 2 (2020), pp. 197-211 (p. 201).

[25] Hezekiah, ‘Intuition and Excess: Mona Hatoum’s Measures of Distance and the Saturated Phenomenon’, p. 203.

[26] Hatoum describes in an interview turning down an invitation to discuss her work on an Arabic radio station because she realised that she could only discuss her practice in English, the language in which it was conceived. See Joanne Morra, ‘Daughter’s Tongue: The Intimate Distance of Translation’, Journal of visual culture, 6. 1 (2007), pp. 91-108 (p. 10).

[27] This point about the quality of the sound of the conversation is elaborated through the use of a psychoanalytic frame in Griselda Pollock’s reading of the work that I engage with below. See Griselda Pollock, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, Migratory Settings, (Brill, 2008), pp. 247-70.

[28] Pollock, ‘Moments and Temporalities of the Avant-Garde “in, of, and from the Feminine”‘, p. 815.

[29] Pollock, ‘Moments and Temporalities of the Avant-Garde “in, of, and from the Feminine”‘, p. 803.

[30] Pollock, ‘Moments and Temporalities of the Avant-Garde “in, of, and from the Feminine”‘, p. 813.

[31] Pollock, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, p. 247.

[32] Pollock, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, p. 248.

[33] Pollock, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, p. 262.

[34] Pollock, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, p. 263.

Antoni, Janine, and Mona Hatoum, ‘Mona Hatoum by Janine Antoni’, BOMB Magazine, (1998) <https://bombmagazine.org/articles/mona-hatoum/>

Crone, Bridget, ‘Bodily States of the Image: Proximity and Distance in the Performance and Video Work of Mona Hatoum’, (YouTube, 2016)

Hezekiah, Gabrielle A., ‘Intuition and Excess: Mona Hatoum’s Measures of Distance and the Saturated Phenomenon’, Paragraph (Modern Critical Theory Group), 43. 2 (2020), 197-211

Hutchinson, Kristen ‘Intimacy and Distance: Mona Hatoum at the Western Front’, Luma Quarterly (2020) <https://lumaquarterly.com/issues/volume-five/019-winter/intimacy-and-distance-mona-hatoum-at-the-western-front/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]

Meigh-Andrews, Chris, ‘Video Installation in Europe and North America: The Expansion and Exploration of Electronic and Televisual Language 1969-89’, in Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film, ed. by A.L. Rees, Duncan White and David Curtis (London: Tate Publishing, 2011), pp. 125-37

Morra, Joanne, ‘Daughter’s Tongue: The Intimate Distance of Translation’, Journal of visual culture, 6. 1 (2007), 91-108

O’Pray, Michael, ‘Moving On: British Avant-Garde Film in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s’, (2017) <https://lux.org.uk/moving-on-michael-opray-2002/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]

Pollock, Griselda, ‘Beyond Words: The Acoustics of Movement, Memory, and Loss in Three Video Works by Martina Attille, Mona Hatoum, and Tracey Moffatt, Ca. 1989’, in Migratory Settings (Brill, 2008), pp. 247-70

———, ‘Moments and Temporalities of the Avant-Garde “in, of, and from the Feminine”‘, New Literary History, 41. 4 (2010), 795-820

Roberts, Tom, ‘The Actt Workshop Decaration Provides Financial Security and New Audiences for Independent Film and Video Workshops’, <https://www.luxonline.org.uk/histories/1980-1989/actt_declaration.html> [Accessed 31 August 2022]

‘Variations on Discord and Divisions’, <https://legacywebsite.front.bc.ca/events/variations-on-discords-and-divisions/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]

Ghada Habib is a PhD candidate at the University of Leeds in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. Her project focusses on John Akomfrah and her research interests include post-colonial and feminist perspectives, artists moving image, and experiments in academic writing. Ghada’s PhD project is AHRC funded through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities (WRoCAH) and this essay was the output of a WRoCAH Research Employability Project.