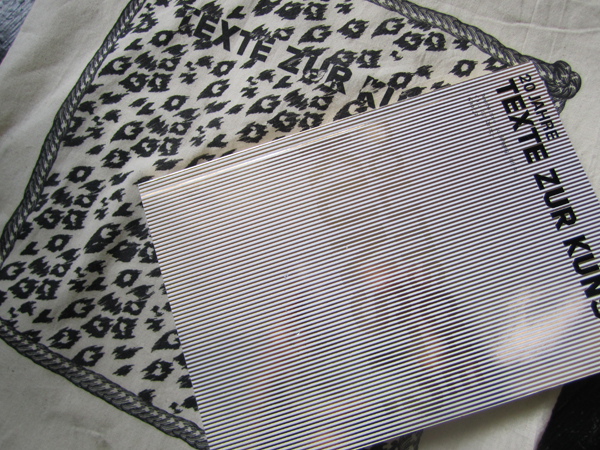

As if to propose the relationship between contemporary art and its theoretical discourses in which it trades and/or the occasion it marks is both glamorous and difficult, the cover of the twentieth anniversary, 80th edition of the Berlin-based journal Texte zur Kunst is a page of slim, vertical metallic gold and white pencil stripes. Turned into the right light, the words POLITISCHE KUNST? can be read, emerging through the slightly ridged, elegant and shiny bars, the appropriately sheer manifestation of a pleasurable and luxurious, elegant and intelligent discernibility (as enjoyable as the paper the book is printed on and the satisfying way its pages flip).

So too the public symposium at Berlin’s Hebbel-Theatre am Ufer with its recently refurbished mushroom coloured seats, receding balconies, art deco wood veneer proscenium: sold out weeks in advance tickets were the hottest in town. Testament to the magazine’s particular currency and to the energy, engagement and volume of the city’s avid practitioners (artists, writers, thinkers) this was still no less than remarkable for a seven-hour-plus, three-panel-discussion showcase of international critics, theorists and artists. Anywhere else it might have seemed excessive, but here felt like a near ritualistic call and response to/from something that might be described as a generous constituency.

The biopolitical was pervasive – Foucault’s word for the ways in which personal life might by spoken in relation to, as being written and affected by political power in all its forms. By which I mean speakers were as much considering what it is they do for a living and why as they were more generally observing the symposium’s umbrella proposition, a partial quotation from a 1973 Joerg Immendorf painting in which a unionist bursts into an artist’s studio, demonstrations visible through the open door and demands of him where he stands with his art, abridged for the day’s purpose as Wo stehst Du, Kollege? (Where do you stand, colleague?).

Thus the anniversary live event and publication skirt similar territory, most broadly characterised as this relationship between art and not-art, or art and life/studio and street, or aesthetics and politics. These things being distinct from each other also shown as joined by a membrane that is variously porous to more or less radical degrees, considered from the perspectives that shape contemporary artistic practice; of course not only production, but exhibition, criticism, theory and philosophy, curatorial determination, the market, institutions etc.

But while the first language of the publication is always German, with only selected articles translated into English, the first language of these discussions was, curiously, exclusively, English. An internationalist nod maybe, but testing ideas and precise positions mediated in a language that the speaker has less of a command over become more of a wrestle than a clarification and sometimes the going was tough – especially in the first session where Franco Berardi’s sharp gesticulations about the immediate political present, including the student protests in London were potentially absurd, baroque pinnacles of this group of critics’ – Sabeth Buchmann, André Rottmann, Luc Boltanski (almost entirely, grammatically unintelligible) – articulations of their own current situations: New Spirit of Criticism? The Biopolitical Turn in Perspective.

The other two sessions – Between Specificity and Context. Social Art History Revisited (Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Isabelle Graw, Andrea Fraser) and From the Anti-Aesthetic to Aesthetic Experience? (Jutta Koether, T. J. Clark, Juliane Rebentisch, Helmut Draxler) – were easier on the ear even while their general timbre was often like witnessing some of the most serious, concerned and capable minds staring into their own (our?) abysses.

Their words remain with me, to be unravelled as I/we go, as it becomes possible. At the time it sounded like a difficult though not unwelcome pain nonetheless alleviated in both panels by the resonating frequencies of the artists’ contributions. In their very different ways both Andrea Fraser and Jutta Koether made material of theatricality (latent for other speakers despite the venue which not-inappropriately they otherwise rendered a conference hall) to the extent that they embodied positions (our/my situation?) as much as explained them. Their generosity was comparatively tangible.

Fraser performed herself, the difficulty of speaking, her incremental turn towards psychoanalysis. Koether stood at the lectern with a brass and hot pink coloured rod and a matching small painting of her own (abstract from where I was sat in the balcony, a piece of foil and bit of netting stuck on it) and gave a virtuosic anti-talk for the sake of aesthetics, desire, expression, sporadically breaking into stomping, stumping the rod on the floor, a jerking, half-dance squat and, well, chanting – with a self-humour not eclipsed by her conviction – that culminated in the clarion-call as rock ‘n’ roll something: “We’ve gotta get fucked up, we’ve gotta get fucked up.” Quite. And that process is for me, like reading this publication, significantly continuous, an unravelling, an open-endedness, a mode of engagement amidst or against a set of codes. In the opening words of founding editor and publisher Isabelle Graw: “Texte zur Kunst is here to stay!” Thank you very much.

Where do you stand, colleague? Art criticism and social critique

Texte zur Kunst: 20 Years

Hebbel-Theatre am Ufer, Berlin, 11 December 2010

Ian White is an artist and Adjunct Film Curator for the Whitechapel Gallery, London, as well as working on independent projects. He is the Facilitator of the LUX Associate Artists Programme and a writer. He curated ‘Tense Present’, a guided tour of artists’ film and video in the Luxonline collection.