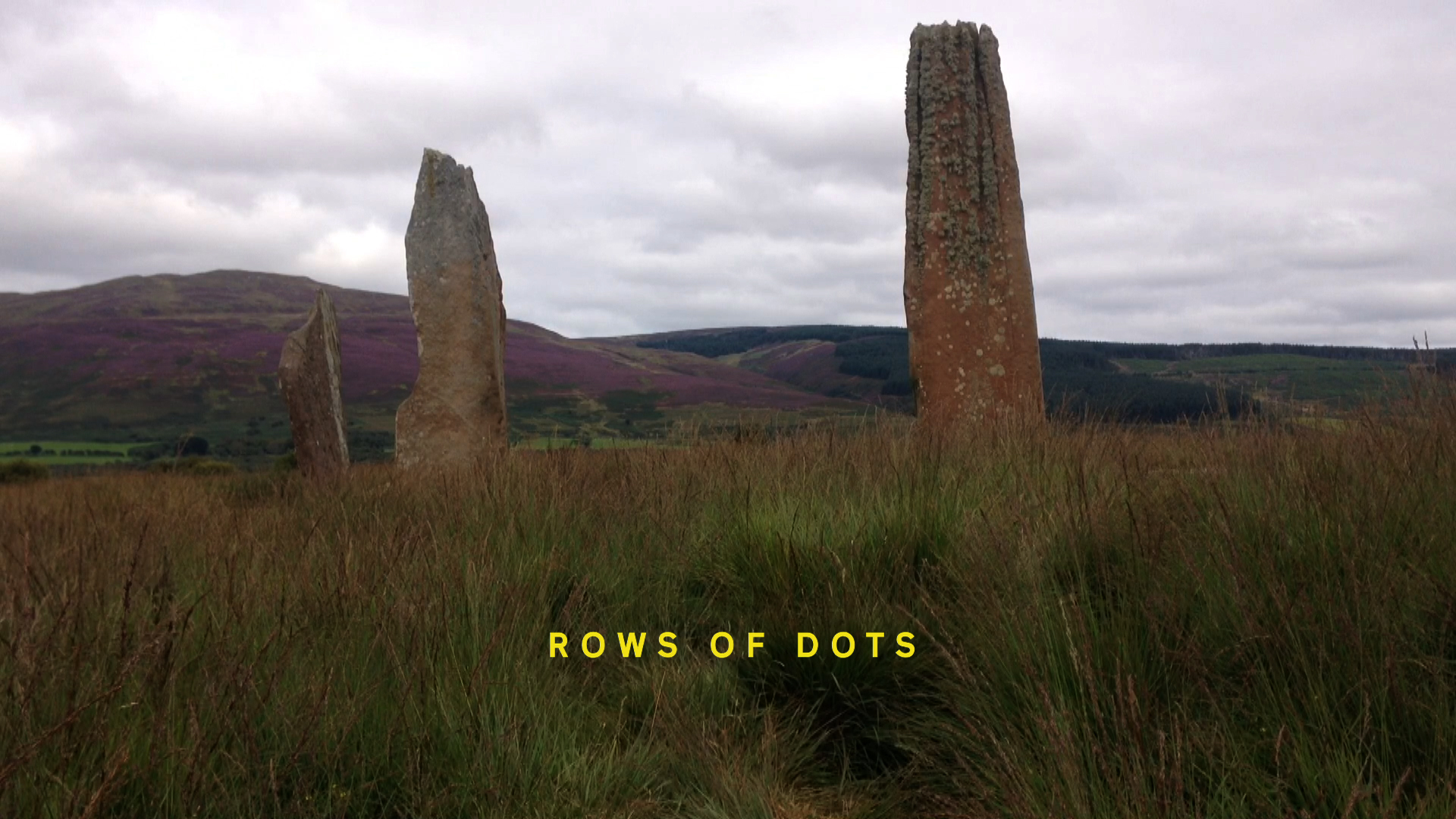

“One of the great difficulties facing anyone who attempts to unravel the problems of the ancient world is that of names. The deities of antiquity have a very great number of names. Not only were they known by different names in different places, but they often had at least three different phases—old, middle aged and young—which were all known by different names in one place.” This excerpt from Julian Cope’s study of British megalithic sites is read aloud in Charlotte Prodger’s film BRIDGIT (2016); meanwhile, a red transport truck is seen gliding along a highway under grimly lit fog, the camera moving at roughly the same pace, but parallel, far off. The gentle brushing of dirt off this archaeological fact is done in relation to the eponymous Bridgit—or Bride, Brid, Brig, Brizo of Delos, Bree—is a fertility goddess from the Neolithic era who is positioned as the loose centre of the film, from which others unravel. “The idea behind taking a name appropriate to one’s current circumstance was that identity isn’t static.”

The self is a kind of green room, whatever size it needs to be for the innumerable selves within it—named or unnamed, dead or alive, singing or silent, remembered, exiled, or lost to natural slippage—the bass of a beating heart throbbing against the wall. Prodger’s essayistic, autobiographical moving image works are comprised of fragments, fixations, and footnotes, arranged together like “moving points on a grid” (as she says about a number of standing stones in the above). Despite the disorder such a description may imply, it’s clear while watching that her formal choices are as intricate as they are intuitive. She tells me that while editing SaF05 (2019), “to help me with structure, I was drawing diagrams of the various height levels in the film that are seen or described. An aeroplane, a missile, a drone, the ground, a submarine. And then intersecting with that, the timeline […] of different autobiographical narratives throughout the film, different dates, from 12 years old until now.” The seams welding these disparate sources—which span geographies, formats, time periods, states of consciousness, and authors—are tight, and attractively exposed.

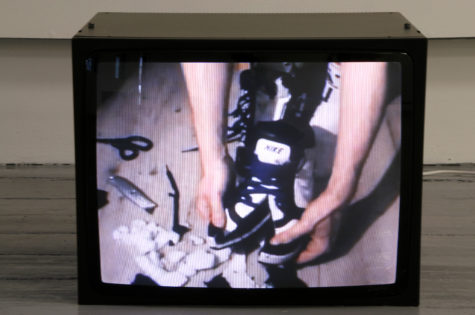

Colon Hyphen Asterix, Charlotte Prodger, 2012

Colon Hyphen Asterix (2012) opens with a low-fi video ripped from YouTube, in which our subject takes a long, serrated bread knife to the top of the shoe he’s wearing and begins to saw, effortfully yanking and pushing the blade through tough layers. At the same time, Prodger reads emails from friends who recount an early morning visit to a gay club, “bear types dancing inwardly to hard beats in near darkness,” and the gradual teasing open of shutters to let the daylight in. Another voice goes on to read the description, comments, and tags of a different video posted by the same user, NikeClassics, of two athleisure-clad teen boys in identical box-fresh sneakers, who ultimately slip into each other’s shoes. (“For my voiceovers, I often ask friends to read out my own personal, diaristic content—people I feel an affinity with and affection for,” Charlotte explained, a diffusion of her own subjectivity, outward and polyvocal.) The viva voce comments range from horny to homophobic to outright confused, and all the while, my attention to the delivered text—whether epistolary or written for search engine optimization—is tested by the prospect of violence. The knife continues, seemingly past the gap between the hallux and the other toes, and yet our protagonist persists with beguiling intensity. While the contents of the video seen and the video described are themselves erotic (homosociality, foot fetishes, and erotic destruction), the filmmaker’s cunning misalignment of the material steadily borders an outpouring of its own. “I’m interested in that splitting, that slight difficulty for the viewer, on the edge of obstructive.”

This syncopated, strategic splicing of personal texts, found data, and descriptions of footage delivered through voiceovers that align abstractly with what’s in the frame characterizes Prodger’s formal approach. “I love doing that surgery,” she tells me, “tessellating layers.” The effect is less assemblage and more musical harmony, the resonance of each part’s essential note in the euphony of the whole. For example, in SaF05, which loosely centres on the search for a lion(ess) identified by the Botswana Conservation Trust to have traits strikingly more akin to its male counterparts, the following notes are arranged on the same staff: a dashcam shot of the road leading to Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels in rural Utah; a recollection of the artist’s first sexual encounter (with a radiographer); a micronarrative about a house keeper tasked with making Baked Alaska for a laird on his birthday; and, a boundary marker in an olive grove in Paxos delineating which family the grove belongs to. In each work, there is this carefully calibrated tension that inheres in the space between individual parts, which invites quiet speculation about the tethers amongst them and the subjectivity(/ies) that is their shared site. The scripts are distinctly economical, explicit, and literary, flooding the subtextual floor.

SaF05, Charlotte Prodger, 2019

The steady, unaffected vocal delivery, whether by Prodger, her kith or kin, crystallizes this levelling effect. Correspondences, journal entries, stories, and other defenses against forgetting take on the air of reportage, meeting the more matter-of-fact material on a shared plane, which in turn recolours it as individuated, interior, and sometimes even warm. In one moment, we hear: “In the months after she died, I had repeated dreams in which I was bartering and bargaining, negotiating deals, sacrifices, or swaps in order for her to come back”; and, in the next: “Date: 21st November 2015. Start time: 05:55. Location: -19.5242040123.63942514940.05.0. Behaviour: moving. Behaviour time: 08:30. Who: SaF05. Habitat: acacia scrub. Count: 2. End time: 09:23.” The unique but similarly mannered voices are key to this structure, and there’s something darkly satisfying about them: percussive, unrelenting, sometimes addictively repetitive.

At first mildly disoriented by the documentary information for its tonal contrast to the easy-drinking autobiographical material, taken together, SaF05 has a kind of sublime weight. After watching, I sat alone with a glass of peppermint tea in the old boat garage refashioned into the slick, stony Scotland Pavilion, the doors rolled up, the rain coming down. Eventually, I walked out into it, across the small footbridge over the Canale di San Pietro, with an opacity in my chest, a sense that something had happened, a need to not speak for a while. Prodger told The Guardian her works “start with a sense of ‘how I want them to feel, rather than what I want them to do.’” The ciphers, the apophenia, the orchestrated coincidences, the knowing smirks thicken into a communicative register all its own—one about queerness, yes, but more of it—maybe too slippery, sly to be pinned down by those untroubled by language’s strict framing of reality (and thus eliding co-optation).

LHB, Charlotte Prodger, 2017

In LHB (2017), Prodger says: “I haven’t felt so overcome and possessed by something in a long time—possibly ever,” about the Pacific Crest Trail. She’s toggling back and forth between reading about people who are undertaking the 3000 mile path from the Southwestern USA to the border of Canada—reading them “talking in minute detail about […] what they’re eating, what they’re eating out of, and what utensil they use to eat their food, and how much that utensil weighs, what they’re carrying, how much it weighs, what they’re wearing, how much it weighs, what they started out carrying, what they switched out”—and watching flicks by a couple named Cole and Hunter who bring in various thirds for amateur cavorting. The film starts with the camera moving quickly at chest height through a thicket of tall yellow flowers, like a pollen-carrying insect, and later, Prodger says the only time she’s paid for porn was to see more of a boy with “pale eyelashes and a ginger shaved head and a pink mouth and pale ginger facial hair and a large wasp tattoo across his chest.” Later, she’s seen pissing in the woods, meanwhile making mention of the bandanas that women hikers use to wipe themselves, which they tie to the outside of their bags to let dry, everyone knowing what it’s for (a lowkey allusion to the hanky code, used by queers to wordlessly signal what kind of sex we’re into). Flashes of electricity jump from detail to detail, these works like exercises in attunement, which makes them engrossing. Citing the trans theorist, author, and artist Allucquére Rosanne “Sandy” Stone, Prodger says that when we communicate on a narrower bandwidth, “in certain ways, we engage more deeply, more obsessively, even.”

In Stoneymollan Trail (2015)—which is named after an ancient burial path outside of Glasgow where Prodger lives, and includes footage spanning 1999-2015—the screen goes black for a few full minutes midway through. Suddenly intimate, like talk radio in my ear, she reads an excerpt from Samuel Delany’s memoirs, The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction in the East Village. He writes of this cruising spot down by the water near dawn: “To step between the waist-high tires and make your way between the smooth or ribbed walls was to invade a space at a libidinal saturation impossible to describe to someone who has not known it. Any number of pornographic filmmakers, gay and straight, have tried to portray something like it […] and failed because what they were trying to show was wild, abandoned, beyond the edge of control, whereas the actuality of such a situation, with thirty-five, fifty, a hundred all-but-strangers is hugely ordered, highly social, attentive, silent, and grounded in a certain care, if not community.”

Stoneymollan Trail, Charlotte Prodger, 2015

Delany’s distinguishing between what “libidinal saturation” seems like to the unacquainted versus what it is like drums up a similarly common misreading of the natural, earthly world: a daedal web of interlocking systems so often thought of as lawless, random, and savage. After all, a landscape is not an image but a consonance with too many parts to count, the biggest free jazz band, and Prodger gets this. “I feel very cautious about the term ‘landscape’ as one thing, like a homogenous, romantic blob,” she says, approaching them instead “as the distinct individual locations that they are.” Landscapes figure appreciably, either subtly rhyming with the work of association carried out by voiceover, or foregrounded as sites unto themselves, indexing all kinds of activity historical, social, political, spiritual, or organic. Prodger said of Holt once: “she believed that coincidences have inherent meaning, and they’re parts of a kind of mathematical pattern that has an abstract significance within the universe,” and this deft, heavy alternation between control and awe seems to offer the precise scaffolding for Prodger’s own work.

Here, I’m reminded of the termite mounds in SaF05—shot on the dusty, dry plains of the Okavango Delta—these universes collectively constructed by the spit of their inhabitants, crude structures (“very industrial looking, like sputtered concrete (same colour as Sun Tunnels)”) that conceal their expansive intricacy. “Some of them were like 9 feet high but the visible part above the ground is the small part,” Charlotte tells me. “Under the ground they can go to 40 feet.” Across the flat, these mounds are the only points of elevation. “Anthropomorphic spectres, analogues of human bodies” is what they became to her, soon finding that the magnetic pull she felt to them rivaled the pursuit of SaF05. It’s fitting, then, that each character from her past is given an alphanumeric name comprised of three letters and two numbers, like SaF05’s, and that the mounds are used as chapter headings: reminders of the subterranean, the sublimated at each turn. Dovetailing from Prodger’s turn in BRIDGIT away from gay (male) erotic aesthetics, the film angles towards a more amorphous, more diffused articulation of queer subjectivity and female attachment.

Each work reads as though Charlotte is using the tip of her finger to slowly, sedulously trace a thing’s contours, every part of it—not so much to comprehend it, but to sustain proximity, to think of nothing else, to nurture its associations, and then trace them too. A comprehensiveness driven by uncanny, unresolved attraction; ergo, the unflinching inclusion of logs, lists, and other formal records, to say nothing of the insatiable thirst that makes itself intoxicatingly plain now and then. Like the bit about the lone dredger fisherman described in Stoneymollan Trail, who continually pulls up a rectangular cage from the sea, releasing its contents onto the floor of the boat. She talks about it like this: “Each time, he kicks about, sorting through it, and every time, I want to see everything, all of it, to know the contents fully, and this goes on and on, this continuous sequence, and it felt like the end of the film, although it wasn’t. And there were other parts of the film, but I would like it to have been just that. I could’ve watched it for hours, the rectangle being lowered in, over and over again, different contents each time.”

Jaclyn Bruneau is a critic, writer, editor, and currently the Editor of C Magazine in Toronto. Her work can be read in The Brooklyn Rail, Canadian Art, Cinemascope, Momus, and in the form of accompanying texts for Erdem Taşdelen (Mercer Union, Toronto); Karen Kraven (Latitude 53, Edmonton); Vanessa Maltese (The C Magazine Annual Contemporary Art Auction, Toronto) and others. It can also be found in the books Mourning Anthology (Art Metropole, Toronto, 2019); Ressources Humaines (FRAC Lorraine, Metz, 2019); Lay It On Thick (self-published by Natascha Nanji and Palin Ansusinha, Bangkok, 2019); and Responses(Wil Aballe Art Projects, Vancouver, 2018). She’s given talks on exhibitions and projects by more than 20 artists. www.jacbruneau.net