In the winter of 1972, Joyce Wieland drove north of Montreal to the small town of Mont-Laurier in order to make a film about the Quebecois activist and journalist, Pierre Vallières. With a small crew consisting of herself and two other women — Judy Steed recording sound and Danielle Corbeil acting as translator — Wieland shot what was to be one of the last films she made during her artistic career. Pierre Vallières (1972) lasts as an articulate distillation of both her radical sensibility as a filmmaker within the context of structuralist film, as well as a piece of experimental evidence of a key moment within Canadian political and social history.

Wieland had only just returned to Canada after living in New York City since 1963, where she had become productively embedded in the city’s experimental and avant-garde film scene. Upon arriving in New York, she began attending Jonas Mekas’ Filmmaker’s Showcases at the Gramercy Arts Theatre. Despite it being still very much a predominantly male community, Wieland was welcomed into the scene by the dancer and filmmaker Shirley Clarke and both she and Wieland were among the few women who were producing films alongside artists such as the Kuchar brothers, Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs, Jonas Mekas and others.

As exiles from Toronto, both Wieland and her then husband Michael Snow had found a dynamic affinity with this film community, where an inclusive, open and collaborative spirit allowed for the production and reception of artists’ experimental film. Although having created a few shorter films while still living in Toronto, it was in New York that Wieland turned to film as a primary material in her practice. During her time in New York, she made fifteen films, all of which show the influence and integration of the tenets of structuralist film, while also indicating to her own particular sensibility for the medium.

It is important to note that Wieland’s return to Toronto in 1971 was, in part, a direct result of the establishment of the Anthology Film Archives and the unequivocal exclusion of her work from the collection, despite being a key figure within the community out of which the archive was established. This, in addition to the reception of her longest film she made while still in New York, La Raison avant la Passion / Reason over Passion (1967-69), Wieland stated in an interview that she ‘was made to feel in no uncertain terms by a few male filmmakers that I had overstepped my place, that in New York my place was making little films’[1].

Yet, at same time, the nationalistic timbre of her solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada in 1971 marked her increasingly urgent interest in her relationship to Canada — something that she would explore in innumerable ways throughout the 70s — that also contributed to her return to Toronto. Lucy Lippard described Wieland as ‘both liberal and nationalistic’[2] as she was entirely unapologetic about her seemingly naïve, yet utterly knowing, politics in the heralding of what she saw as a nation disappearing due to the imperialist tendencies of Canada’s neighbours to the South.

It was in her loose trilogy of overtly political films, La Raison avant la Passion / Reason over Passion, Rat Life and Diet in North America (1968) and Pierre Vallières, where Wieland took on the complex political climate of Canada, a country which was undergoing its own process of self-determination as Canadian identity was being forged through the rhetoric of Pierre Trudeau, Montreal’s Expo 67 and the rising Quebec Separatist movement.

The subject of Pierre Vallières is Vallières himself, who was a vital figure within the separatist organization, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). Vallières had become politicized at a young age having been born into a working class neighborhood in Montreal. In his early career he worked as journalist for La Press and Pierre Trudeau’s liberal magazine Cité Libre, but as the FLQ movement gained momentum it was in 1966, while protesting the plight of the Québécois in front of the United Nations in New York, that he was arrested and jailed for four years on charges relating to FLQ violence.

During his incarceration he wrote his impassioned and polemical book, Nègres Blancs d’Amerique (White Niggers of America), where he wove his own personal narrative into a larger history of oppression, calling for armed action in the liberation of Quebec from Canada. After being convicted of manslaughter (which was later overturned in 1973) he was released on appeal in 1970.

Later that year in the escalating violence of the October Crisis and the kidnapping of the Minister of Labor, Pierre Laporte, Trudeau, to the shock of most Canadians, invoked the War Measures Act, where the police had the right to detain anyone suspected of involvement with FLQ-related violence without any formal changes. Over 450 individuals were detained, including Vallières. Laporte was then found murdered, for which the FLQ claimed responsibility and it was at this time that Vallières turned his back on the FLQ in support of the non-militant political arm of the FLQ, the Parti Québécois.

In the wake of the October Crisis, Wieland — who had been a vocal supporter of Trudeau throughout the 60s — now found his actions as Prime Minister objectionable. In an interview from 1986 Wieland reflected on her disillusions about Trudeau’s politics: ‘I think when you see the narcissism. I mean, there is a wonderful brain, but when the heart is closed over then it’s not that much fun anymore.’[3]

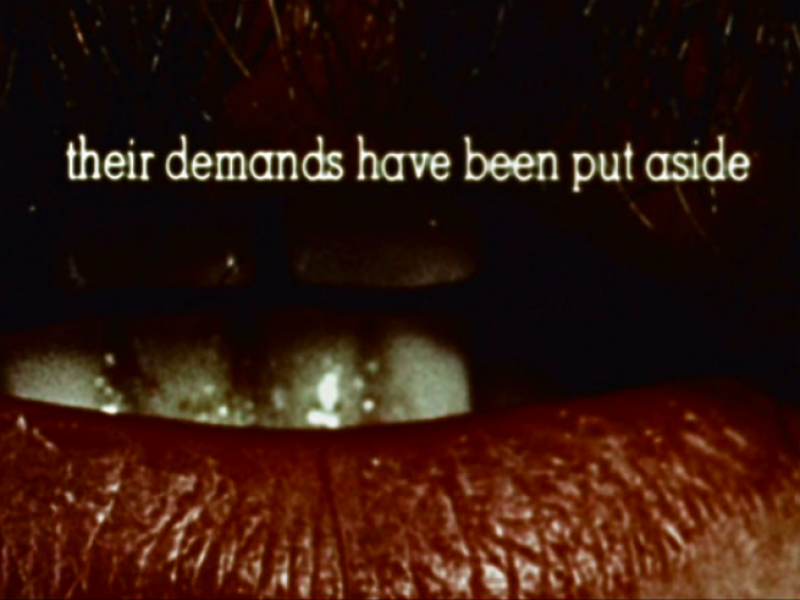

Her choice of Vallières as a filmic subject perhaps reflects Wieland’s desire for embodied politics, as she saw the film as a ‘mouthscape’ where ‘here is a close-up of his mouth, on and through which you can meditate on the qualities of voice, the French language, the French Revolution, Géricault’s color, etc.’[4] The work is composed of three rolls of film, with Vallières delivering a speech for each one: ‘Mont-Laurier’, ‘Quebec History and Race’ and ‘Women’s Liberation’. Wieland enacts a number of classically structuralist techniques, for example, the length of the film is determined by default to the length of each reel of 16mm.

Joyce Wieland, Pierre Vallières, 1972, film still © Joyce Wieland. Courtesy of Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre

Joyce Wieland, Pierre Vallières, 1972, film still © Joyce Wieland. Courtesy of Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre

(CFMDC)

Wieland’s self-reflexive, authorial presence is included within the frame as we hear her voice off camera as each roll of film is being changed. Throughout the entire thirty minutes of the film, Vallières’ lips, moustache, teeth and physical pronunciation via his speaking mouth fill the frame. In a manner similar to her use of 537 algorithmic combinations of the film’s title in La Raison avant la Passion / Reason Over Passion, superimposed over the image of Vallières mouth are English subtitles, translating his words, providing a didactic, textual contrast to the sensuality of the orating mouth.

Here at once and the same time Trudeau’s vision of a Canada united through a softly enforced federal bilingualism is delivered through the radical and poetic words of Vallières. While speaking resolutely to the historical, systematic oppression of the Québécois, his rhetoric also slips into deeply felt poetics, such as:

so that each may live his life and so that we may all live as well, as fully, and as happily as possible with the maximum enjoyment of all that makes up what we call life, life on earth. As I know of no other life, I think the reason for this struggle is to put in this life the maximum joy, and for this we’ll have to work together to liberate ourselves of all forms of domination and exploitation…

Vallières’ affirmative position is not unlike Wieland’s own words, when she said: ‘It’s important to … just … feel the beauty of everything and be as positive, as positive as possible’[5]. She said this in an interview that similarly enacted the desired fluid ideal of bilingualism, as she was interviewed in French by the curator Pierre Théberge, Michael Snow acted as translator as she gave her answers in English (as she did not speak French herself), which Snow then translated back into French for Théberge.

The yearning for communication in Pierre Vallières is given equal part within the film as the man himself; the written words inscribed on the filmic surface become a graphic assumption of an English audience, secondary to the image and sound that is privileged to the French-speaking Vallières. Wieland ends the film with a repeated left to right panning of the snow-covered landscape outside the window of Vallières apartment. In her work, Wieland relentlessly returns to Canadian landscape as inert, vast and ultimately uncapturable as subject and image and in her effort to loosely document, the images she creates never over-determine the subject into a singular whole. By filming Vallières from a static but fragmented visual point of view, she represents him as a discursive subject, open to change and contradiction. Despite its rigid structure Wieland manages to express a pluralism that was consistently integral to her practice as a filmmaker while also allowing herself the impulse to make a film:

dealing with the mouth of a person that was put in jail without trial for three years… Also the teeth and the particular lower-class kind of accent are imbued with a kind of working-class speech. The teeth of a poor man. And the rolling of the tongue and lips – the whole thing about what is a mouth.[6]

Later in his career Vallières turned his back entirely on the separatist movement and did not vote in either the 1980 or 1995 Quebec referendums on sovereignty, focusing his activism instead on gay rights and First Nations self-government.

Soon after she made this film, Wieland shot Solidarity (1973), about a workers; strike at the Dare factory in Kitchener, Ontario and her feature length film The Far Shore (1976), were the last films she made that look at Canada as an intrinsically political subject, after which Wieland’s own focus turned away from film and into a more introspective exploration of feminine subjectivity. What becomes markedly clear is that she was producing films in an historically disjunctive moment, prior to the social and ideological achievements of second wave feminism. This historical context makes all the more clear the uniquely radical approach she took the idea of a ‘political’ film or ‘political subject’, creating space for a heterodoxical position within the margins of structuralist film.

[1] ‘Kay Armatage Interviews Joyce Wieland’, The Films of Joyce Wieland. Ed. Kathryn Elder. Cinematheque Ontario Monographs: Toronto, 1999, p 158

[2] Lippard, Lucy. ‘Watershed: Contradiction, Communication and Canada in Joyce Wieland’s Work.’ Fleming, Marie, ed. Joyce Wieland. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario and Key Porter Books, 1987, p 3

[3] Kristy A. Holmes-Moss and Barbara Stevenson, ‘Joyce Wieland: Interview and Notes on Reason over Passion and Pierre Vallières’, Canadian Journal of Film Studies / Revue canadienne d’études cinématographiques 15, no. 2, p 119

[4] Iris Nowell, Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art, ECW Press, Toronto, 2001, p 332

[5] ‘Interview with Joyce Wieland: Interviewer, Pierre Theberge, Interpreter, Michael Snow, 28 March I971’, Joyce Wieland: True Patriot Love/Veritable Amour Patriotique, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1971, p 156

[6] Kristy A. Holmes-Moss and Barbara Stevenson, ‘Joyce Wieland: Interview and Notes on Reason over Passion and Pierre Vallières’, Canadian Journal of Film Studies / Revue canadienne d’études cinématographiques 15, no. 2, p 120

Joyce Wieland, Pierre Vallières, 1972, film still © Joyce Wieland. Courtesy of Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre

Joyce Wieland, Pierre Vallières, 1972, film still © Joyce Wieland. Courtesy of Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre