The Otolith Group is an artist led collective founded by Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun that integrates film and video making, artists writing, workshops, exhibition curation, publication and developing public platforms for the close readings of the image in contemporary society. The Group’s work is formally engaged with exploring the legacies and potentialities of documentary practice, the essay film, postcolonial archives, cosmopolitan modernisms and science-fictions. Nationally and internationally, the Group have curated and

co-curated work at film festivals, programmes and exhibitions including the touring exhibition The Ghosts of Songs: A Retrospective of The Black Audio Film Collective 1982-1998 at FACT and Arnolfini (2007) Harun Farocki. 22 Films: 1968-2009 at Tate Modern (2009) and the touring programme Protest, conceived as part of Essentials: The Secret Masterpieces of Cinema commissioned by the Independent Cinema Office (2008).

The Group held their solo exhibition A Long Time Between the Suns: Part I and Part II at Gasworks and The Showroom, London (2009). Their numerous group exhibitions include British Art Show 7, Nottingham, London, Glasgow and Plymouth (2010), Manifesta 8: The European Biennal of Contemporary Art, Murcia, (2010), Universes in Universe: 29th Sao Paolo Biennal (2010), Star City: The Future under Communism, Nottingham Contemporary (2010), Universal Code, Power Plant, Toronto (2009) Translocalmotion: The 7th Shanghai Biennale (2008), Destroy Athens: 1st Athens Biennial (2007), 2nd International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville (2006), New British Art: Tate Triennial (2006) and Homeworks III: A Forum on Cultural Practices, Masrah Al Madina, Beirut (2005). In 2010 The Otolith Group were nominated for the 10th Turner Prize.

In this interview, the Group discuss their Turner Prize exhibition on display at Tate Britain, and their new work Hydra Decapita (2010), exhibited at Manifesta 8, Murcia, in relation to a research practice that combines essayistic montage, discursive space and didactic methodology.

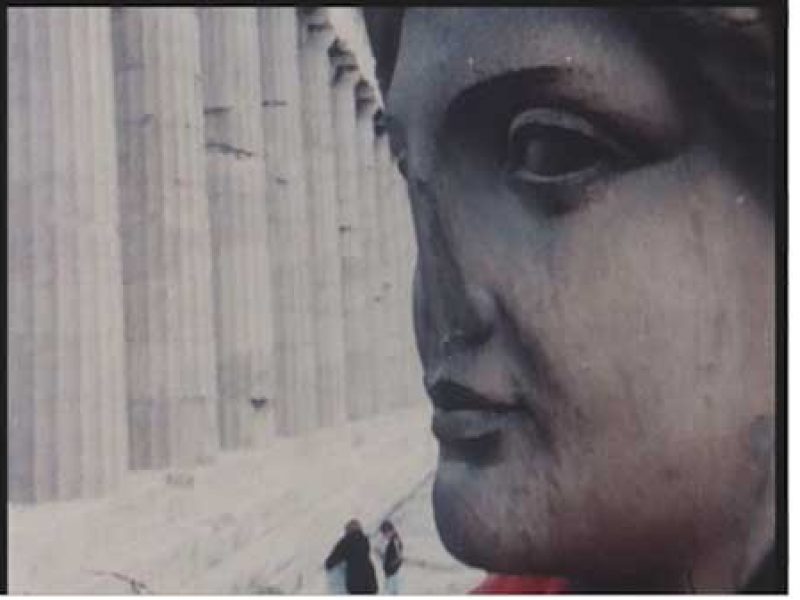

GL: I was interested to talk about the relation between the different strands of your practice, from texts to more event based, research or discursive spaces. For instance the work that is currently on show as part of the Turner Prize at Tate Britain incorporates Otolith III (2009), the final work in the Otolith trilogy, Inner Time of Television (2007), a thirteen monitor installation of Chris Marker’s television series The Owl’s Legacy (1989) and artists book entitled Inner Time of Television as well as The Image in Question, a series of three roundtable discussions and screenings during the exhibition as well.

AS: We have always been interested in working with the idea of integrated practice in the way that Black Audio Film Collective were thinking about the politics of making, production and distribution in the mid 1980s. In terms of how we think about our work, it helps us to present the ideas that we draw upon in public, in order to think through the connections and the divergences and to make those continuities and separations visible, audible and shareable today.

GL: To some extent then I suppose that comes down to how things can have visibility, or rather the different modes of visibility that are valorised. There are a lot of works that use different other works to try and say something, because ultimately, why would you say something badly yourself, if you can use someone else’s work that’s already done that better. Or because you love that work and you want to show that to someone. Often though, this type of work can be misconstrued as part of an appropriation discourse, where showing someone else’s work is about ownership, rather than presenting another visibility or means of distribution.

AS: I would say that Inner Time of Television is not a project of appropriation. We knew that The Owl’s Legacy existed so we mailed Marker in the summer of 2007. He mailed back and explained how and why the work was so difficult to see and sent us the French version and the English subtitled version. What we wanted to do was analyse why this work was made for television at that time. We wanted to formulate an argument for presenting it in a gallery context in order to think through the role played by art in relation to a cinematic encounter with philosophy in the context of television.

KE: The Owl’s Legacy is a television essay, one of a small number of television essays, from the same era as Noël Burch’s series on silent cinema entitled What Do These Old Films Mean? and Godard’s series of television-essays that culminates in Histoire(s)du cinema. We are preoccupied by all the forms of the essayistic. The essayistic is not a question of genre; it emerges from a discontent with the duties of documentary and a skepticism towards the obligations of what we think documentary should do. It is the name for a discontent with documentary that is registered in and through the mode of documentary.

AS: Which then plays itself out in the form of discursive events.

KE: The essayistic does not necessarily entail a certain kind of voiceover that is often called poetic; nor does it entail a certain use of archive or a music. It is a distance towards with a certain kind of documentary that is accompanied by an admiration for that tradition. It is an argument with with image and sound by image and sound.

Perhaps it is also related to the way that we learnt and are still learning how to make films. All that we know about films comes from watching them, writing about them, talking and thinking about them. So every time that we put on an event, this discussion allows for a return to learning. Each time that we programme a film, each time that somebody invites us to present a films that entails a scenography of instruction that is inseparable from production.

AS: A lot of the discussions that we were having, especially around the time of the Black Audio Film Collective retrospective in 2007 emerged from a dissatisfaction with the lack of visibility of experimental documentary that questioned the profilmic event. I wanted to make work that was informed by the essay-films of Black Audio Film Collective and by the experimental documentaries of Anand Patwardhan. Patwardhan is one of India’s most important documentary filmmakers. Some of his films were commissioned by Channel 4 in the 1980s but by the end of the 1990s that stopped and it became impossible to see his work. In that gap, certain questions remained. Where might this work be presented? How might it be presented? What arguments could be deployed in order to think through this kind of practice? We felt that the work of Black Audio Film Collective should be exhibited and editorialised as an experimental practice. We had many discussions about these kinds of ideas. Those discussions have continued, and still continue, but we wanted to make them public, to share these ideas.

KE: Part of the point of doing events in public is to meet with people that share your preoccupations. The events are always simple in their format so that they can be complex in their content. A space is opened for a discussion that emerges from a para-academic atmosphere. There is a great desire for these activities and many artists such as 16 Beaver and no. where have staged and continue to work on different forms of these kinds of invitations. There is an ongoing real desire to participate in discussion events; it could be said that we are the product of these screenings and discussions.

GL: I think, in terms of the essayistic approach anyway, there is an understanding that reading is, in itself, productive, so it is not about owning another product but making something in relation to something else. You are readers, and in that way, you’re all reading each other’s work, and building a discourse out of that. Then, once you get into that, you get into this kind of distribution visibility problem, so how can we disseminate this material when the terms of visibility are based upon whether something can be pre-validated or determined, or more so, owned.

AS: What we want to do is to construct events that allow people the space and the time to unfold their ideas. Ideas are quite fragile. Where do we really get the chance to really explore their thinking?

KE: The discussions that we do are designed to enable us to engage in close listening.

GL: Like most works. That’s how to generate ideas and discourse. When you’re trying to write something, and you talk to someone about it, it’s ten times clearer afterwards.

KE: Yes, for the Turner Prize, the idea is to make visible an integrated practice that involves these different platforms. Inner Time of Television is in keeping with Marker’s vision of collaboration that he started in the 1950s. What preoccupied us in Inner Time of Television was the opportunity to confront contemporary audiences with a kind of spectatorship that has largely disappeared. We think of the work as a monument to dead television, because it resurrects a form of attention that no longer exists in broadcast television in a gallery setting.

GL: Yes, there is a real problem of contemporary verification, whether in terms of formal reference or fashionable parlance. Perhaps the controversy over something can make visible an assumption or an issue taken for granted. At the same time, strategies of shock are somewhat problematic.

KE: Controversy speaks to that disturbance. People bring their habits of thinking and the work challenges that, not overtly, but in a gentle way. Inner Time of Television does not quite fit the kind of work that people are used to seeing resurrected.

AS: Black Audio Film Collective operated in film festivals, on television and in art galleries. That complex tripartite way of working has its difficulties that people do not understand how to think about it. Today, you have to demonstrate your commitment to the art world or you do not count as an artist.

GL: And somehow you have to make a choice. And this is very frustrating. I think it’s also to do with what can be purchased, perhaps. What can be deemed collectible as an object. But I think you get some crossover with a kind of a structuralist practice when you start with the structures of what is possible within a medium. You might start looking at some idea of montage, and then that can only sometimes interestingly relate to how images are in relation to each other, and how different images are visible in relation to each other. I don’t know if beginning from the point of montage predicated towards non-narrative, is central to a work. Hopefully you make work because you want to say something and do something, and as such the problem of presentation is always addressed.

KE: The essay-film is always making several arguments and its existence proves the success of the argument. If it works, it retroactively proves the productivity of your proposition. The essayistic has a propositional form to it that we enjoy. What makes Thom Anderson’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) one of the most significant essay films of the last decade is that Andersen asks himself questions that bring an urgency to the project.

GL: Yes, there’s an interesting relationship there between an idea of say, an aesthetic education, and the kind of essayistic form of a film.

KE: We have all been brought up on the idea that the worst criticism you can make of a film is to say that it is didactic. You could call it pornographic or scatological and most artists would accept those descriptions but the worst thing that you can say about a film today is that it is lecturing you. We like films that pose arguments. Our favourite filmmakers are not afraid to take on that instructional aesthetic.

AS: They have come to the decision of how to represent an argument and those decisions are aesthetic decisions.

GL: Actually saying something, or being able to say something. Saying, I want to show you something – here you are. I think this is very apparent in this issue of visibility and verifiability. No one wants to say anything other than what has been already sanctioned as acceptable, valid. So nothing much gets said at all.

KE: Having a position is as important to us than being ambiguous and ambivalent. When you make an essay film, you are assembling this constellation by building blocks of movement, image and sound that have their own logic to them. I think the essayistic could be argued for as what we call a thought form.

GL: Yes, I was reading some Eisenstein the other day on the relationship between montage and architecture, architecture being the most kind of consistent in how he understood film to work. I think the text is actually called Montage and Architecture, and really it’s interesting how he marries something that I think is, generally, segregated because they are understood either as actual physical forms or in terms of conceptual impetus and not the dialectical relation between them. That relationship between the montage idea and the essay form, like you say, can perhaps work, if the work itself seems intact, if it fights its own argument, because it has an autonomy, because it’s strong as an object. Perhaps, in that way, that’s what makes it similar to something like architecture, because this can really do something very strong or resistive, have a presence.

The Otolith Group’s Turner Prize Exhibition is on at Tate Britain, London until 3 January 2011. The Otolith Group are also showing as part of the 29th São Paulo Biennial, 25 September – 12 December 2010, ‘There is Always a Cup of Sea to Sail In’, Sao Paolo, Brazil. Also Manifesta 8, Murcia, Spain until 9th January 2011 and with forthcoming Tour of Mumbai / Delhi/ Kolkatta in December and solo show at MACBA, Barcelona opening in February 2011.

Gil Leung is a writer and curator based in London. She is Distribution Manager at LUX and editor of VERSUCH journal.