LUX opened on Shacklewell Lane, Dalston, in 2002 to continue and extend the work of its predecessors as an agency particularly based around the distribution and collection activities of the LFMC and LEA. Working through distribution, collection, exhibition, screening, professional artists support and education, LUX continues advocate for and support the practice and discourse of artists’ moving image in the UK. In the summer of 2016, LUX relocated to Waterlow Park, Highgate after 14 years in Hackney. In 2014 LUX also established LUX Scotland, a new agency for the support and promotion of artists working with the moving image in Scotland, more information about this at www.luxscotland.org.uk

Over the past 50 years LUX has worked with most artists who have worked with the moving image in the UK, these include amongst others: Ayo Akingbade, Ed Atkins, John Akomfrah, George Barber, Clio Barnard, Black Audio Film Collective, Ian Breakwell, Stuart Brisley, Duncan Campbell, Bonnie Camplin, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Adam Chodzko, Steve Claydon, Phil Collins, David Critchley, Nina Danino, Vivienne Dick, Cerith Wyn Evans, Shezad Dawood, Benedict Drew, Stephen Dwoskin, Luke Fowler, Ryan Gander, Beatrice Gibson, Peter Gidal, Dryden Goodwin, David Hall, Mona Hatoum, Emma Hart, Claire Hooper, Onyeka Igwe, Jaki Irvine, Derek Jarman, Isaac Julien, Sandra Lahire, David Lamelas, Torsten Lauschmann, Malcolm le Grice, Tina Keane, Patrick Keiller, Anja Kirschner, Andrew Kotting, Tamara Krikorian, Mark Leckey, Anthony McCall, Stuart Marshall, Simon Martin, John Maybury, Ursula Mayer, Rosalind Nashashibi, Grace Ndiritu, Annabel Nicolson, Uriel Orlow, The Otolith Group, Jayne Parker, Gail Pickering, Sally Potter, Morgan Quaintance, Elizabeth Price, Charlie Prodger, William Raban, James Richards, Lis Rhodes, Ben Rivers, Margaret Salmon, Carolee Schneemann, Lucy Skaer, John Smith, P. Staff, Corin Sworn, Stephen Sutcliffe, Grace Schwindt, Guy Sherwin, Alia Syed, Margaret Tait, Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, Jon Thomson & Alison Craighead, Edward Thomasson, Mark Titchner, Mark Aerial Waller, Mark Wallinger, Emily Wardill, Gillian Wearing, John Wood & Paul Harrison, Rehana Zaman, Andrea Luka Zimmerman and many more…

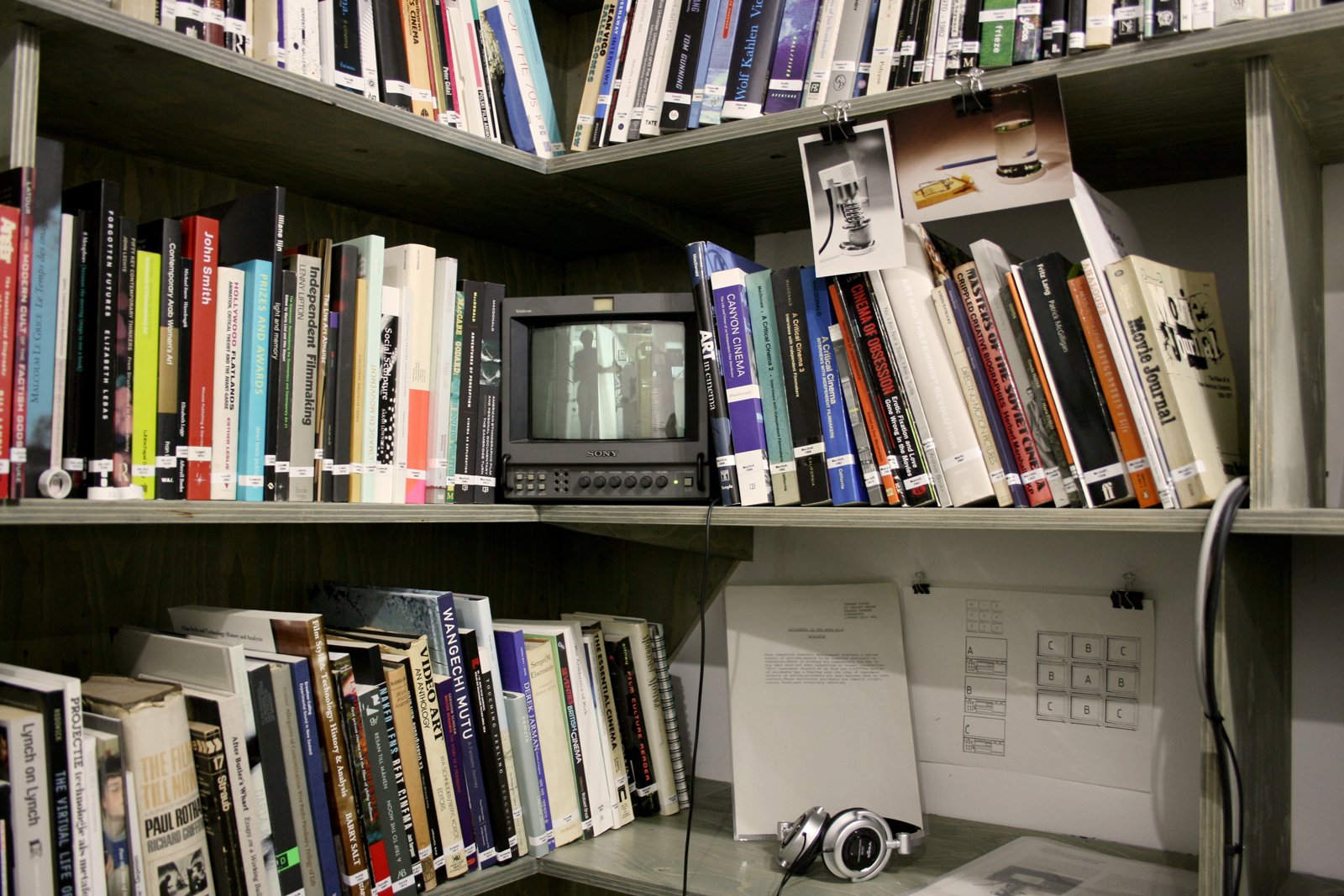

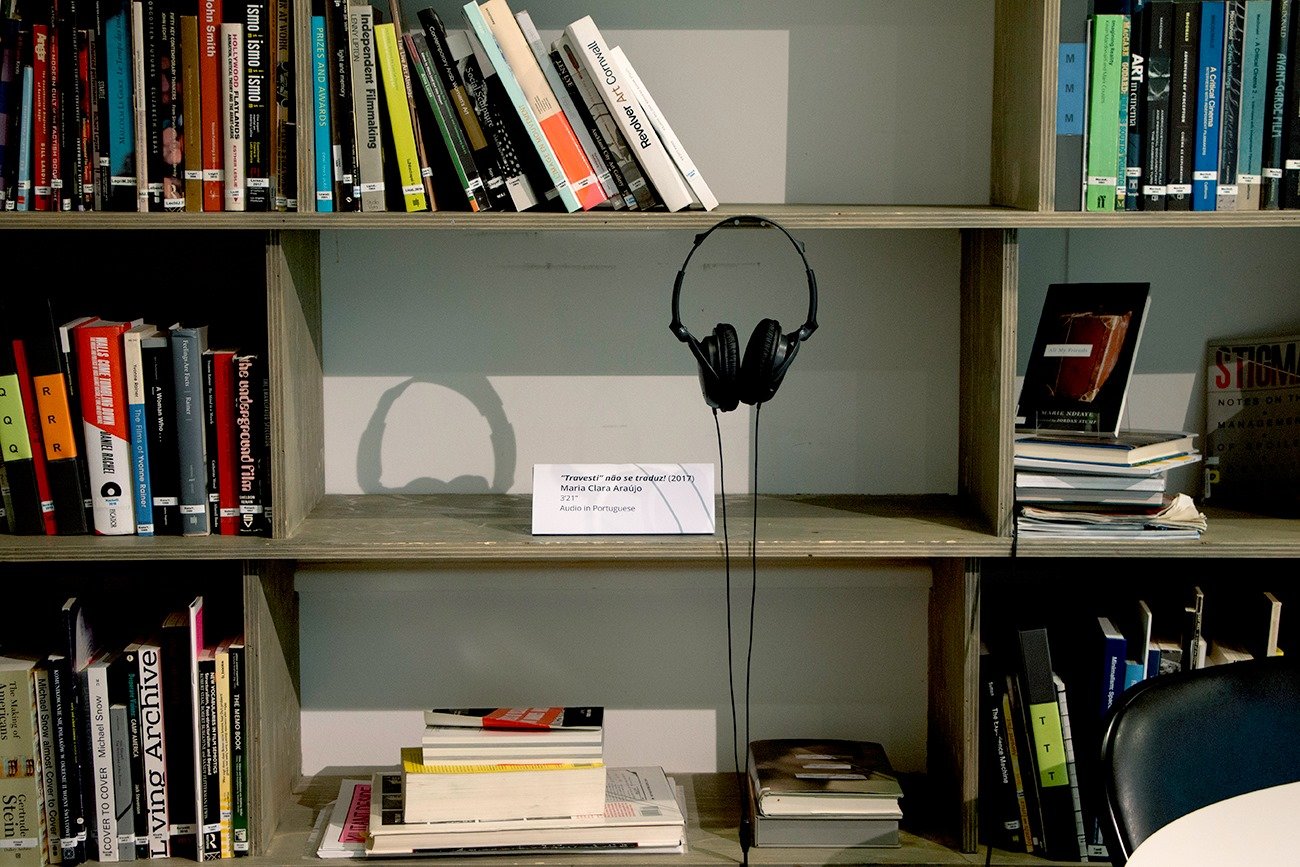

LUX Library London

LUX Library London

Further Reading

Reaching Audiences Distribution and Promotion of Alternative Moving Image Julia Knight and Peter Thomas, Intellect.

A History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain A History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain David Curtis, BFI

Shoot Shoot Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative 1966-1976 Mark Webber (ed), LUX