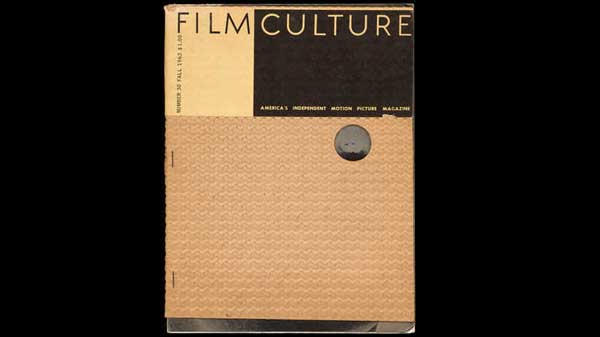

Imagine an eye – it looks out from an inch-wide hole stamped out of a piece of unusually corrugated cardboard on the cover of a magazine. A single eye looking through a hole has an unusual vantage point.

On the one hand it is immobile, its vision is restricted to a limited field, yet without the confusions of binocular vision, the view can be understood as clearer, more commanding, than the chaos of everyday sight. This is the organizing viewpoint of perspectival vision, which dominates lens-based representation. This authoritative visuality has been routinely criticized (in theories of painting, photography and the cinema) for putting limits on vision and for severing sight from the rest of the body. (1)

The magazine we are looking at, and is looking at us, is the special issue of the journal Film Culture published in 1963 dedicated to, and for the most part authored by, the young avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage.(2) It is his eye that peers through the hole – it is his eye we are invited to see through. For many of his audiences in the years since the issue was produced that disembodied eye sums up all that is uncomfortable about Brakhage’s position – it signifies his passionate advocacy of the sovereignty of the eye and in turn his ambivalence to the particularity of the body of which it is a part. At the time of the journal’s publication Brakhage had, by the age of thirty, completed over twenty-five experimental films – moving throughout the 1950s from wunderkind to statesman for the movement. He began writing the texts for the special issue of Film Culture, which became known as Metaphors on Vision, at the moment his filmmaking shifted from creating short cryptic and expressive narratives towards a greater interest in abstraction.

It has been rarely noted that the artist George Maciunas constructed the magazine cover’s metaphor for vision; his contemporaneous work was deeply opposed to the celebration of the sovereign eye and its spatial mastery that the design suggests, and looking at it further makes clear the kinds of questions Brakhage’s filmmaking was negotiating in the early 1960s. Maciunas was the leading light of Fluxus, an international network of artists producing small-scale multiple works and performances that characterized a real shift in artistic practice away from the idea that fine art was to be valued through vision alone. Caroline Jones has recently discussed the way in which the senses were ‘bureaucratized’ in Post-War American culture (particularly within the influential criticism of Clement Greenberg) with eyesight retaining its place at the apex of the sensorium, over the impurities of smell and touch.(3)

Around the top of the issue of Film Culture a printed strip of opaque paper advertised the availability of Fluxus works through mail order. The following year a reader could have purchased A-Yo’s Finger Box, the prototype of which was developed by Maciunas into a multiple work, where the viewer-participant’s role is one of poking a finger into a hole in order to feel an unknown object hidden within. Finger Box – like the Film Culture cover – isolates a body part, yet it is not the all-seeing eye but rather a forlorn finger. Fluxus, taking its lead from the historical avant-garde, played its part in what Martin Jay has described as an ongoing challenge to the ‘occularcentrism’ of traditional philosophical thought by developing a practice that drew attention to the body and its vicissitudes.(4) In his Fluxus Manifesto, published in the same year as Metaphors on Vision, Maciunas purloined dictionary definitions of the group’s name, one definition stands out for its emphasis on the bodily – Fluxus is ‘a flowing or fluid discharge from the bowels or other part.’(5) This turn to the body and away from the eye is a challenge to the image of the artist as a privileged visionary. Fluxus works like Finger Box turn the viewer into an active, haptic participant who is the only person capable of completing the work. In this way the formation of Fluxus marks the turn at that moment, catalyzed by the writing of Marcel Duchamp and the teaching of John Cage, towards seeing meaning as made in the work of art by its audience rather than created by its author. Maciunas’ practice is far from that of the vision of Brakhage that he initially seems to be presenting in his design, an image of a single filmmaker as an experimentalist visionary auteur.

Yet to understand Brakhage’s visuality in this way is to fundamentally misread what the filmmaker was attempting to articulate about the potential of the eye. Brakhage recognized the power of the eye – but wanted to take it further, make it do more. In his texts he recognized that the opposition between mind and body (an opposition that pivots around questions of vision) was a false division and that the eye worked in tandem with the rest of the senses. Brakhage’s films aimed to stimulate those other senses located across the body through vision. Maciunas’ textured cover, which stimulated touch as it was turned, opened to reveal an image of Brakhage’s whole face printed onto a sheet of semi-transparent paper. Here the printed body occludes transparency: this is as rich a metaphor for what the filmmaker has to say as the eye peering through the hole. This tension between the ocular and the bodily versions of vision, conjured by the turn of Maciunas’ page, is central to understanding the dialectical value of Brakhage’s filmmaking at the time of the magazine’s publication. These tensions are clearly laid out in the text and in his films, as techniques of superimposition lack of focus, and close-up shots of skin consistently ask the viewer to identify with the limits of vision and the heights of bodily sensation.

(1) See for example Jean-Louis Baudry, ‘Ideological Effects of the Basic Apparatus’ (1970), in Philip Rosen (ed.), Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), p. 292.

(2) Film Culture, 30, (Fall 1963)

(3) Caroline Jones, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

(4) Martin Jay, Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth Century French Thought, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

(5) The manifesto was published by Maciunas himself in 1963, as a single sheet, incorporating his own handwriting alongside purloined dictionary definitions.

James Boaden is a lecturer in the history of art at the University of York. He is currently working on a book about the circle of Stan Brakhage from 1950-1965. He has curated film screenings at BFI Southbank, Tate Modern, and La Virreina, Barcelona and has published essays in Art History, Oxford Art Journal, and Little Joe.