Stan Brakhage: It’s my problem, at the moment, that I am once again, or let’s say especially for the first time, trying to make a portrait of Jane. This is after years and years of Jane’s image being central to film after film after film. And this is weighted with the problem that every now and again Jane will say, well you’ve never gotten an image of me. So here I go for the first time – again.

Hollis Frampton: Why is it that he can’t make a portrait of you Jane.

Jane Brakhage: He just uses me.

Stan Brakhage: Oh, boy, now I’m in trouble! The whole women’s lib movement at this instant descends on me like a puddle of harpies!”

“Stan and Jane Brakhage (and Hollis Frampton) Talking”, Artforum, January 1973(1)

In the late 1960s Brakhage had squabbled with his main distributors at the Film Makers’ Coop and removed his work from circulation there. Although one doubts that the FMC kept him in any kind of financial security at any stage of his career, his decision to leave seems to have caused great financial anxiety. One way to both have his films shown and to earn money was to travel with his films and introduce them to audiences in art schools and universities. It is important to remember that at this time, in the USA, the university was a central intellectual node in the burgeoning national counterculture, and towards the end of the 1960s became a site for unrest. The formal nature of Brakhage’s work, and the unrelenting focus on his isolated domestic world became quickly contentious with the students sitting watching as the audiences for his work. Often they would ask whether the domestic focus didn’t marginalize ‘bigger’ issues, in short whether it was ethical to simply abandon the public sphere at a time of war. Brakhage’s clear response to those criticisms was 23rd Psalm Branch, which managed to combine his auteur style with the representation of current affairs.

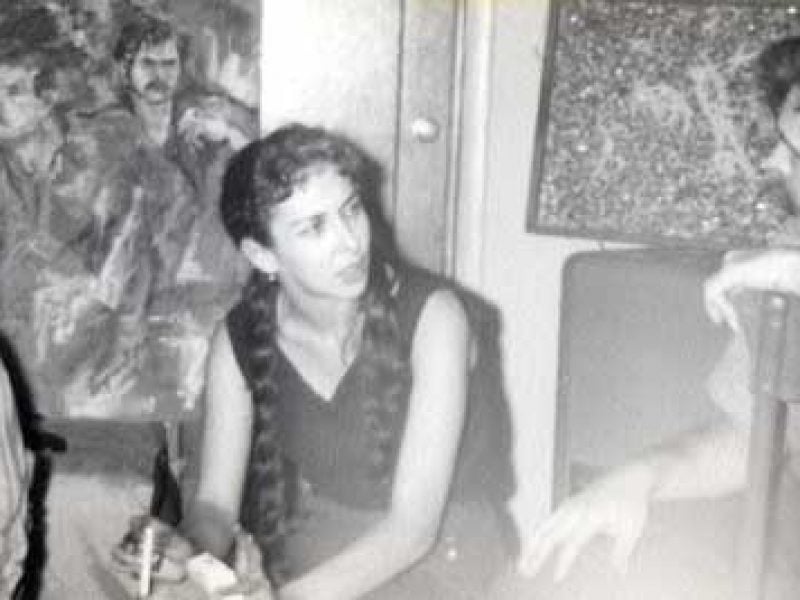

Later in the decade his critics were often feminists, who questioned the way in which domestic labour was conventionalized within the household shown on film. Many of Brakhage’s Songs – the 30 films he made on 8mm film from 1964 to 1969 – show his wife Jane taking on the main share of the labour of bringing up the couple’s five children. This labour often seemed obscured by the way in which Brakhage attempted to represent the autonomy and agency of his child protagonists (especially in the epic Scenes from Under Childhood, which he worked on from 1967 to 1970). Patricia Mellencamp has discussed the way in which the “hand delivery” of films on the university circuit resulted in the filmmakers’ account of their work after a screening often replacing any kind of critique of the film itself, and she demonstrates the way in which these appearances built up a boys-club of star players.(2) As a student in the early 1970s, the feminist filmmaker Barbara Hammer was a spectator at those types of screenings (and later in her film Audience (1981) went some way to dislodge their conventions). She recounts in her recent memoir that she drove Stan and Jane Brakhage from the airport when they visited San Francisco State University to screen their films as part of James Broughton’s class titled ‘Visionary Film’. Hammer writes, “I was fascinated with Jane. She was so interested in the world around her while Stan seemed caught up only in his ideas. She picked seed pods from trees and plants and told me she had written a lexicon of dog language.”(3) Jane Brakhage’s role in Stan Brakhage’s filmmaking at that time echoes the description Mellencamp gives for women in the field of avant-garde film in the 1960s and 1970s where they were more often than not “a sexual partner for the nomadic artist […] wife, great mother, business manager, and general caretaker”.(4) As a student Hammer was a sensitive viewer to this situation and was reluctant to place Jane Brakhage in the position of artist’s wife and instead was interested in her as an active agent in the making of the worldview of the films.

Several months after the screening of Brakhage’s films in San Francisco Hammer wrote to Jane Brakhage to find out if she would be willing to be the subject of her master’s thesis film, she wrote ‘”I have been intrigued with his [Stan’s] image of you and how different a woman’s would be”.(5) Hammer traveled to the couple’s isolated home in Lump Gulch, Gilpin County, Colorado in 1974, taking with her a 16mm camera, an open reel video camera and sound recording equipment.(6) A recording of Jane Brakhage’s voice recounting aspects of her daily routine and her perception of her own self-image plays over the top of both still and moving black and white images in the film Hammer made there. Brakhage discusses her relationship with the animals that surround the cabin in which she lives with her family, she tells of how she can read their attitude, and even understand the language of dogs. She talks about her role as a housewife as active and various before describing the physical sickness that followed almost a decade of child rearing. The photographs capture Brakhage at work weaving at her loom and interacting with the small menagerie of animals that lived with the family, there are also images of the children at play inside the gas-lit house. Stan Brakhage appears nowhere in Hammer’s film – the filmmaker recalls that he was probably away for the period of time in which it was made. In her proposal for the film Hammer wrote:

‘Jane is significant as a far reaching and sensitive humanist in her own right as attested by those who have met and talked with her. She is a thinker as well as a doer and a grand “feeler”, to use Jungian terms. She is independent, taking long donkey rides into the Rockies on her animal […] She is iconoclastic enough to live at 9,000 feet elevation in a ghost town and strong enough to be a direct descendent of our courageous pioneer foremothers.’(7)

Hammer clearly refigures Jane Brakhage from the role of muse to the position of active agent within the house, celebrating her daily rituals and her sensitivity to the world around her. The film does not attempt to record everyday life in the household, but rather attempts to record Jane Brakhage’s own reflections on that life. It is the sound that particularly marks Hammer’s film out from those made by Stan Brakhage – allowing Jane Brakhage a voice, and pointing to the inadequacies of the visual for representing subjective experience (paralleling the techniques of Yvonne Rainer’s contemporary film Lives of the Performers). Hammer’s best known works from the time – Dyketactics (1974), Women I Love (1976), and Multiple Orgasm (1976) – each significantly develop a visual vocabulary that Brakhage’s films had helped to make legible in the previous decade. However those films use a variety of techniques that question the primacy of the visual that Brakhage extolled in his writing, and in that sense they can be related strongly to the seemingly singular documentary technique used in Jane Brakhage.

(1) Reprinted in Robert Haller ed, The Brakhage Scrapbook: Collected Writings, (New Paltz, NY: Documentext, 1982), p. 180.

(2) Patricia Mellencamp, Indiscretions: Avant-Garde Film, Video & Feminism, (Bloomington: Indiana, 1990), p. 9.

(3) Barbara Hammer, Hammer! Making Movies out of Sex and Life, (New York: The Feminist Press, 2010), p. 66.

(4) Mellencamp, p. xi.

(5) Letter from Hammer to Jane Brakhage dated Oct 9 1973, Barbara Hammer Archive – I would like to thank Barbara Hammer for her generosity in allowing me access to her rich archival materials.

(6) Hammer also retains video footage from the visit, which includes interviews with Jane Brakhage’s parents and much of the unedited interview that provides the voiceover for the film.

(7) Barbara Hammer, ‘Master’s Creative Work Proposal’, December 1973 submitted to San Francisco State University. Barbara Hammer Archive.

James Boaden is a lecturer in the history of art at the University of York. He is currently working on a book about the circle of Stan Brakhage from 1950-1965. He has curated film screenings at BFI Southbank, Tate Modern, and La Virreina, Barcelona and has published essays in Art History, Oxford Art Journal, and Little Joe.