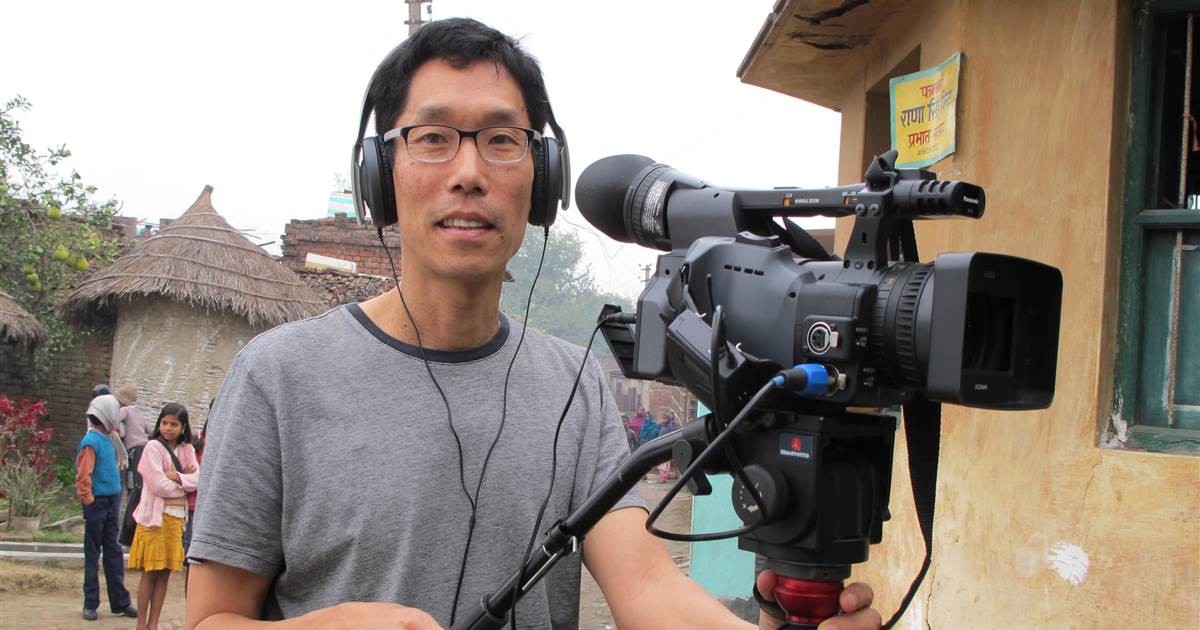

Richard Fung is a video artist, writer, theorist and retired academic who was born in Trinidad in 1954. After graduating from the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), he finished a BA and MA at the University of Toronto and worked in community video and television before initiating a video-based art practice. Fung is part of a generation of gay Canadian video artists who came of age in the context of gay liberation, the Toronto Bathhouse raids and the AIDS crisis, merging new technologies, art and activism to energetically explore the intersections of LGBT+ histories and cultures in video. Fung foregrounded the representation of Asian men in pornography while addressing further intersections of colonialism, immigration, racism, homophobia and AIDS and forged witty, personal and erudite forms of cultural activism with works like Orientations: Lesbian and Gay Asians (1984), Chinese Characters (1986) and Steam Clean (1990) and critical analysis with essays Looking For My Penis in How Do I Look? (Bay Press, 1991) and Shortcomings: Questions About Pornography As Pedagogy in Queer Looks (Routledge, 1993). Further to these works Fung has explored his Trinidadian roots, the Asian diaspora and the lives of LGBT+ people as the basis of what José E. Munñoz describes as an auto-ethnography of video. As a founder of Gay Asians of Toronto in 1980, as a queer video pioneer and a Professor at OCADU, Toronto Fung has helped shape queer Toronto and queer Canada for decades.

Watch Chinese Characters here as part of Picturing a Pandemic

Conal McStravick interviewed Richard in lockdown with his partner writer and activist Tim McCaskell in Morocco where they have been since earlier this year.

Richard: Tim and I have been in lockdown in Morocco since March 21st, in fact we didn’t know that lockdown had happened. The Moroccan government have banned people from moving from place to place and for the past two months there’s been a prohibition on people leaving their houses unless they are shopping for food, going for medicine or to perform essential services.

We’re in the countryside and so we can go for walks in the fields during the day. In addition during Ramadan, they have a curfew from seven at night till five in the morning. So we can go into the little town here which is about 20,000 people and use the bank or shop at the market.

The first lockdown deadline was April 20th and then they extended it to May 20th and only yesterday, they extended to June 10th. However, the province we’re in and about half of the provinces in Morocco have had no cases at all. So at this point, I think people are perhaps cynical or don’t take it so seriously here.

Conal: I was in Ireland, just after the lockdown because my father was dying and I went home to say goodbye and help with his care and whilst I was there he died, so I stayed to organise his wake and funeral and to support my Mum.

As my Dad was getting progressively more ill I was travelling back and forth a lot, so I was in Ireland for nearly a month in total and by the time I came back to London about five or six weeks ago I had seen lockdown in three countries.

Richard: Sorry to hear about your Dad. In London are you restricted on going out?

Conal: So the restrictions here were to ‘stay at home,’ since updated to ‘stay alert.’ Previously you could leave for essentials like food shopping, going to the chemist or to go care for other people, unless you were a key worker in which case you were still expected to work.

Up until last week, you were only meant to leave the house for up to one hour exercise once a day but this is now unlimited, however, you’re still expected to work at home if you can. It’s also recommended that you only meet with one other person each day and that you still shouldn’t mix households, but confusingly the guidance varies throughout the UK.

Just to talk briefly about Picturing A Pandemic and the place of Chinese Characters, your 1986 video work within this, I’ve been developing this project recently through research, proposals, writing, workshops and a little teaching to reflect on questions of intersectionality with regard to parallel and overlapping moving image archives, particularly artist’s moving image which I suppose you would say have a broadly queer feminist, decolonial and post-’68 cultural and political drift with regard to these images as ways of staging crises and liberations and therefore as images of survival on screen.

Furthermore, since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic and the global lockdown, how it might be possible to think about these archives and these artist’s images in ways that consider collective and embodied histories, cultures and practices as tools and strategies. Namely how the women’s, women’s health, LGBTQIA, crip and decolonial moving image archives might inform one another and at the same time pose critical examinations of past crises and liberations as modes of and maps for survival in the context of the challenges presented by the current pandemic.

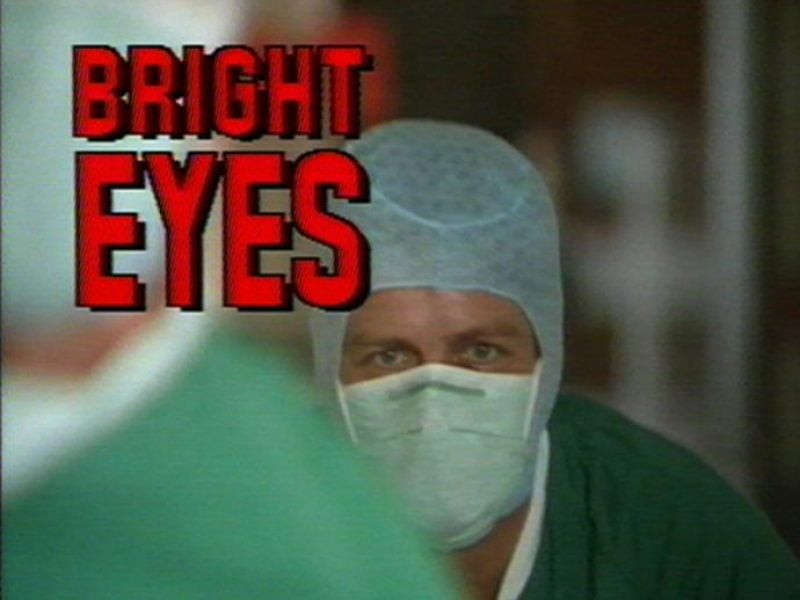

I suggested to Benjamin Cook, LUX Director that perhaps we could start Picturing A Pandemic with Bright Eyes by your friend and peer the late Stuart Marshall, as I’d recently watched Bright Eyes and clips from Stuart’s various AIDS activist works with SLG, a senior LGBT+ group. They themselves said how prescient these works seemed, having lived through the period and as those now most vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of moving out of the AIDS archive and opening out an intergenerational and intersectional conversation around LGBTQIA identities and decolonial critique, I felt it would be prescient to show Chinese Characters as part of Picturing A Pandemic, and to talk to you as a way to open up what I think of as a durational critique present within Chinese Characters and the subsequent works you have made, one which invites re-examination.

Richard: First of all, I would like to say that I met Stuart Marshall, very early on in my career, when his thinking, and in particular his thinking about the politics of images and his concern with the question of colonialism and race in artistic and critical discourse, impressed me.

In Canada, there was a degree of envy many of us has as we looked towards Channel 4

and the opportunities that were given to artists with bigger budgets to reach wider audiences. Those of us who were working in a more artisanal way in Canada took a lot of inspiration from what was going on in Britain at that time. I had my own last gasp of that with Dirty Laundry (1996).

Conal: So to briefly summarise Chinese Characters, this is a 1986 artist’s video that examines the representation of Asian men in North American porn, namely the absence of and desexualisation of Asian gay male sexuality in porn. It does so through a first-person narrative of the artist’s (your) experience and that of peers, staging these narratives by using actors (including yourself) in ways that re-stage and interact with the porn archive.

This includes theatricalised interview sequences and archival sequences from Joe Gage porn films, where, in one memorable sequence, one Asian actor solicits the caucasian porn actor on-screen to explore and act out fantasies and reflect on the ambivalence of searching for positive images of Asian sexuality, whilst being stereotyped or racialised in one’s everyday life.

Actors perform characters and stereotypes in theatrical sets and in costumes that combine ‘Oriental,’ 1980s metropolitan hipster and gay subcultural looks. This is enhanced with a framing narrative of Chinese mythology and chapters that are split up into geographical categories that speak to the dominant othering of Chinese heritage and identities in the Western, colonial present and of ways therefore to decolonise desire.

I suppose we could go into this more in a moment but I’ve been re-reading two essays that you contributed to the essay collections How Do I Look? and Queer Looks, titled ‘Looking For My Penis’ (Fung; 1991) and ‘Shortcomings: questions about pornography as pedagogy…’ (Fung; 1994) written within several years of Chinese Characters which records the journey that you went on as a video artist and a thinker in light of this work up to and including the Safer Sex Short Steam Clean (1990).

Especially how your readings of that work started to change and develop in conversation with other video and filmmakers and as a consequence of the various audiences that the work was being shown to. Is that fair to say?

Richard: Yeah, it’s been a very long time since I’ve looked at the Queer Looks article in particular, but it’s fair to say that one of the things that I’ve tried to do is to keep critically revisiting any position that I’ve taken and to be self aware of the implications in doing so.

Conal: I suppose it would be useful for you to describe some of the motives that you had when you were making Chinese Characters. I think you used the rather wonderful term ‘meta-pornography’, to describe Chinese Characters in Shortcomings.

Richard: Now, in terms of Chinese Characters, of the things I was thinking about at that time, one was a particular feminist critique of pornography. Because within the Canadian context, there were people like Mariana Valverde and Lisa Steele, who had an anti-censorship critique of pornography, as well as the more dominant voices on pornography in the gay movement at that time.

The other thing that occurred to me was that in the process it was often assumed that both the people who are represented on the screen and the people critiquing those images were white. So one of the things that I wanted to do was to bring in this other kind of critique of pornography, one that came from racialized people.

At the time I was organizing with Gay Asians Toronto (a Toronto-based organisation for gay men of Asian heritage founded by Richard in 1980). We had a different kind of critique. We suggested that while on one hand these images were some of the few that validated our sexual desire, on the other hand, simultaneously, these images denied us from feeling desirable.

In the Canadian context, it was very much white dominated. I think it’s important to signal right now that I’m drawing on my partner Tim McCaskell’s work on the way in which Toronto of that period of the 1980s was different to today as one of the most multicultural cities in the entire world, where over 50% of the population is non-white. This was a Toronto in which I could go into a gay bar and see maybe one other black or Asian person.

It’s hard for younger people to imagine Toronto that way and I’ve heard ahistorical arguments around racism at that time, as the ‘community’ demographic was so very different. In fact, Orientations: Lesbian and Gay Asians (1984) my first professional video documentary, two years before that, includes shots of the Gay Pride March. I think that video includes pretty much every person of colour who went by, it might itself give a false impression of how diverse those marches were back then. It’s documentary as a certain kind of false evidence, right?

That brings me to the other question which was dominating my thinking at that time which was the question of voice. So as you rightly pointed out, using first-person narratives, talking about Trinidad and also using different faces because I think two things were going on. One of them is a little joke about Asians looking alike, right? In fact, there are a few people who could not tell that there were different people acting, when we all looked very different!

Conal: In the video!? Oh my goodness!

Richard: Yes! So there is that little joke but also I had just come out of doing an undergraduate degree in film studies where I had studied with Kay Armatage. Armatage had been one of the major programmers at the Toronto International Film Festival and someone who was very key in bringing feminist and black British voices to TIFF at that time.

So I was very interested in those kinds of questions, the idea of whose voices are added and how to represent that, which is ordered by biography, or the autobiographical content represented. I think with a lot of the early work I was trying to say something but at the same instance to create the conditions for its own critique, or even its own undermining.

I was thinking through ways to make a, ‘serious intervention,’ but also, to modify it somehow.

In terms of the ‘meta-pornography’ or the use of pornography, I had read an article and I suspect now it was by a white gay man who was self-flagellating about gay pornography and how terrible it was, etc. etc. I did not want to have Chinese Characters subsumed into that anti- pornography approach to the critique of pornography, which is why I have explicit sex in the video.

Conal: Not to be conflated with the anti-porn brigade!

Richard: Right. What often happens is that you end up with these kind of binary positions, (of sex-positve or anti-porn) or simply defending really tacky pornography. I wanted to say that I could have a critique of the kind of depictions of pornography without falling into the critique that all sexual representations are bad.

Conal: Yes. Just to put this into some context, at the time, you’re making parallel video works dealing with the experience of the Asian diaspora, primarily the history of your own family in Trinidad and you’re deepening an exploration of the intersection of race and LGBT+ culture and politics in the second decade of gay liberation in Canada.

This is happening with the enhanced role that video has in Canada and in Toronto in particular, working with a lot of fellow artists, activists and video makers in particular, who were active in that scene. Looking at your work of that time I see a lot of names of people that I know were active in art and activism.

Tim, your partner, who was active in the leading anglophone AIDS activist organisation in Canada, AIDS Action Now!, has consistently featured in your work. Your friend and fellow video maker John Greyson and various other Vtape artists feature too. (Vtape is an atist-led video distributor co-founded in Toronto by artists Lisa Steele, Susan Britton, Rodney Werden, Clive Robertson and Colin Campbell in 1980).

In terms of production most of your videos at this time were made through video co-ops.

In some senses, were these works collectively produced? And as a community, was that ethos embedded in the politics of Toronto in the 1980s and 90s? I suppose I’m interested in how these things were made, as well as how this wider context figures in the work.

Richard: Now, there are two kinds of overlapping communities here.

I’ll start with the community on screen and since you mentioned Trinidad, I’d say that one of the things I think that is specific perhaps to the way that I produce work whether written or in the video as an ‘Asian’ is my formation in the Caribbean, since I came to Canada already with a kind of anti-racist critique that developed in the black power movement of Trinidad.

A lot of the anti racist discourse among Asians in relation to porn was that they were feeling somehow excluded from a mainstream of images in pornography and I wanted to propose perhaps another kind of erotic attachment or possibilities, which was an Asian-Black relationship which was often absent from that political discussion.

So one of the things about Chinese Characters and you know, the video quality is so poor at this point, I’m not sure one recognizes- is that in the scene towards the end, the late Lloyd Wong is making out with a black man. Doug Stewart is from Jamaica and was and is one of the major forces of black gay organizing in Toronto. Zami, the organization he co-founded, was a very close partner with Gay Asians Toronto and so there’s that activist kind of relationship.

Conal: I recently saw Our Dance of Revolution, in the BFI Flare selection, which is a documentary about the black gay and lesbian scene of Toronto of the 1970s, 80s and 90s and they talk about Zami, the house where many of the featured activists lived and organised, the work of Black CAP (Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention) which Doug co-founded and this is expressed in continuity with present organisations like Black Lives Matter. It’s clear to see there were many overlaps here.

Richard: Yeah. So Philip, the Director, actually used clips from Orientations (1984) in that documentary…

So Zami, Doug’s home was the house that produced Sister Vision Press, the black and feminist of colour publishing press and Lloyd Wong who is the young man making out with Doug became active in the arts magazine Fuse, which was founded by Vtape co-founder Lisa Steele, and where John Grayson worked. I myself later joined the editorial collective.

(Founded as Centrefold in Calgary in 1976 before re-locating to Toronto in 1978 and changing it’s name to Fuse in 1980, the magazine continued until 2013. (During this time the editorial had a keen focus on feminist, ‘lesbian and gay’ and ‘Third World’ issues).

So the Toronto art scene at that time was relatively small. There were a lot of people who were involved in what might be called the progressive scene at that time: the women’s movement, the LGBT+ movement or the lesbian and gay movement as it was then, as well as these sorts of activities in the artist-run centres. It was a very promiscuous scene, and, in some ways literally.

Conal: I believe you were using video co-operatives like Trinity Square Video?

Richard: Most of my work was produced with Charles Street Video, one of two video producing co-ops. The music was by Glenn Schellneberg who worked with John Greyson and is now a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto.

Conal: I’d like to shift our focus from motives, the context, themes and production to the content of Chinese Characters. I love the opening quote which comes from Confucius, which says: ‘Food and sex are human nature,’ and the way in which it’s chaptered by the cardinal points to acknowledge how geographical, categorical difference as a colonial legacy is coded into our cultures and histories.

In particular in the essay Looking For My Penis, you refer back to Frantz Fanon and a prior Caribbean decolonial critique of dominant white cultures and histories, one which hypersexualises blackness in a way that by the same colonial logic places whiteness on a spectrum of intellectual, physical and sexual prowess between blackness and asianness, amounting to a countervailing de-sexualisation of Asians that in your critique echoes in contemporary race-based psychologies, social Darwinism and the sexual representation of Asian men in porn.

You use this example to make a powerful point which I think still resonates, that within these discourses and indeed in our capitalist economies the persistence of a rationale where someone’s physical and intellectual capacities and by extension their sexual capacities are coded in our cultures continues to have material consequences in terms of how one can be educated, how one can find work, how one is desired or valued and indeed how one survives. This of course comes back to the theme of survival for this series of online screenings. That years of austerity and now the COVID-19 pandemic draws our attention to the urgent need to address who is most adversely affected by the politics of the pandemic, of austerity and who therefore is struggling to survive.

In the UK there has been increasing analysis and growing public awareness of the disproportionate number of BAME people affected by COVID-19, including infection rates due to health, living environment, working environments and risks at work. As a consequence this reveals not just who does what in our societies but the demographics of who performs the most risk on the basis of their race or ethnicity in our societies. The disproportionate number of people of colour in high-risk jobs becomes another way that coloniality is re-expressed in the present and this applies in the pandemic and in general.

Richard: To come back and think about Chinese Characters, because I haven’t seen it for a while, you’re reminding me of certain things and why I might have done those things… For example the use of the cardinal points as inter-titles and I think an additional title that says ‘down there’ as well… One of the issues that I’ve been grappling with since then -certainly a word I would not have used at the time- is essentialism.

Intersectionality has entered our vocabulary but I’m not sure it’s always seriously applied.

I find that what is now referred to as queer of colour critique is not always as anti-essenitlaist as it should be. I remember being struck by a passage by Kobena Mercer -and I hope I’m not misquoting him- that the problem with white supremacy is not white people, per se, but a white subject position.

At the same time I was reading something else today by a group of self-defined Asian leftists in relation to the anti-Asian racism that flared up as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, citing the racist legacies of ‘yellow peril.’ Additionally this goes onto to examine China’s treatment of African students and residents and anti-blackness within China.

This is something that has been a pre-occupation of mine because the ‘model minority myth,’ that is perhaps more prevalent in North America than in Britain has been attractive for many people of Asian descent because it has allowed us to negotiate white supremacy in a particular way. I think one of the things you’ve got with BAME people in Britain or BIPOC as we say, is how those terms put everybody of colour in the same boat when these communities experience racism in different, ways particularly with regard to class. This is also true with regard to class, gender and sexuality.

I saw Stuart Marshall trying to work this stuff through, as well as thinking about how these questions figure in representation. Like at the end of Bright Eyes when he filmed Michael Callen re-reading his 1983 speech on AIDS originally made to the New York Congressional Delegation adjacent to the cruising ground at Hampstead Heath, London. It was so brilliant. I was lucky early on in my career to meet people like Stuart, Isaac Julien, Kobena Mercer or Trinh T. Minh-ha. All of those attendant issues around intersectionality are things that I was thinking back then and even more now.

Conal: I’m interested that you speak about the work of Isaac Julien and in your essays you note the work of Pratibha Parmar and Sunil Gupta and the contrasting visibility of Asian artists who are engaging in a similar mode of critique in the UK at that time. Can you maybe describe what that meant at the time. Was there collaboration going on and if at all how did you support one another?

Richard: I don’t know that there was that much collaboration. I think the interesting thing is that these connections were not always made in Canada so much as through New York and Los Angeles, with LGBT film festivals or events like How Do I Look? as meeting places. (How Do I Look? was a conference convened by Bad-Object-Choices a gay and lesbian reading group founded in 1987, that took place at Anthology Film Archives, NYC, October 21st– 22nd, 1989, and later published as a book.) This put people in physical contact and as someone who has put up a festival and who works a lot with film festivals I see a problem with this slippage onto online viewing into an atomisation of public space into private space.

Just returning to what you mentioned earlier regarding risk, despite this utopian idea that we can all be at home, we can each be at our computers, this only throws into relief who’s actually going to be doing your shopping, cleaning your home, taking care of your sick relatives -or yourself- and therefore putting themselves at risk.

Himani Bannerji long ago pointed out a critique of the contradictions of technological convenience in terms of the erasure of public space for South Asian women given the added roles they assumed as moving image moved into the private sphere when Indian cinemas in Toronto closed.

We used to go together from time to time to watch Indian films in Gerrard St, which is an Indian neighbourhood of Toronto. Previously women would get a break from the routine of having to cook for their families when then they would go watch a movie together and maybe go for a meal or to the sweet shop.

But by contrast, when things moved to video, those same women instead of having a break would have to cook for more people, so often friends of her husband’s and the wider family who would come to the house to watch videos. So the switch from video actually served to confine women even more and increase their work load.

So that critique extends to the move from cinemas to video and the way that video is moving to online with platforms like Netflix etc. Where we never have to leave our homes to go to a video store. I am so ambivalent about what these seeming conveniences mean for social interaction and social engagement, where in the past people would come together to watch a film.

I have written elsewhere of the importance of film festivals for marginalized communities like LGBT communities in which individuals may not be able to even recognize each other, they may identify by type or mis-identify others as belonging to that same community, but when they come to a festival or they’re in the same room, those sites, those geographies are places in which those identities become confirmed and constituted.

Conal: There’s an essay by Ian White called Foyer where he talks about the primary space of the cinema not being the auditorium but the foyer, where people meet before and after the screening.

Richard: Yeah, absolutely. In terms of LGBT people, not everybody is visible, many people are stealth, right? So for gay men, at least, it’s historically those physical sites like bars, washrooms, bathhouses or cinemas, which of course are disappearing, in which the community can really constitute itself . Grindr doesn’t lend itself to building a movement.

In any case we don’t have LGBT+ activists as much as lobbyists now. So often lawyers or well connected people make delegations, or you may sign a petition, but that petition again is disembodied. So this lack of embodiment, I think, is affecting movements and communities very, very strongly.

Conal: Just to set aside for one moment the differences in how we are mediated or dis-embodied through our online presence, or through digital intimacies, I suppose one of the things I’m interested in is the specificity of video and the role that video has offered in being a form of activism with regard to other parallel forms of activism like treatment activism in the context of the AIDS crisis.

In as much as you talk about pornography as pedagogy, a videotape had this capacity as an activist and a pedagogical tool. It was something that could be handed person to person and indeed any given artwork or activist work could be shown diversely and widely.

I suppose it would be interesting for me to hear you reflect on how you think video activism or video per se changed the capacities of political activism in the context of the changing relationship between culture and politics at this particular time and the changes in technology since.

Richard: You mentioned sexuality and I think that video, actually, in terms of pornography has made images much more mobile. I spent thirteen years of my life in a gay commune and one of our older members, George Smith, was one of the major strategists and thinkers in the gay movement in Toronto.

George had a 16mm copy of a gay porn classic whose name I can’t remember. You’d have to have access to and know how to set-up a projector, speakers and all this apparatus to see it. He also had a selection of the Joe Gage classics, which I think are brilliant in representing gay American geographies and there was a huge difference in how these could be played and handed from person to person. VHS made those images really, really mobile.

Something I’ve reflected on a lot, is that one of the potentials of video was its reproducibility, but of course we also know how that utopian possibility was undermined by living in a capitalist society in which people had to earn a living.

So therefore, you had in some ways to restrict the mobility of those images through distributors, for example like Vtape who would charge for it. You have the possibilities of new technologies, but then you are living in a place with a particular economic system that requires that the technology will not live up to its fullest potential.

Conal: By contrast, with the internet, which I suppose had it’s own utopian early years and is now somewhat haunted one way or another by it’s own unfulfilled potential as a digital commons, this technology has evidently aided and abetted with global capital to become not only highly commodified, not only something that’s changed how images are distributed, but has significantly changed global societies and econmomies, or geopolitics per se, and, in the process has become infinitely more powerful than anyone could have imagined. It’s worth reflecting on the role of moving images in these economies.

Richard: As somebody who taught video until very recently, it’s interesting for me to observe the way that once young artists, maybe three generations younger than myself, produce a video there’s an assumption that immediately upload it online for free viewing. So this potentially creates an unsustainable situation for the artist or it only becomes sustainable through the branding of the individual, rather than the work itself, or through other means of sustaining a livelihood.

Conal: Absolutely. Indeed at the beginning of the lockdown it felt felt like the neoliberal order that underpinned this was collapsing in a matter of days. It’s another instance where the cultural and political status quo is being challenged and yet as much as you shared your ambivalence about the contradictions of what’s lost as people meet less in public I suppose like you I share a suspicion of the rationale behind rethinking what organizations or institutions can do, and by extension the artists commissioned by them, simply by taking their work online and perhaps further inadvertently atomising public space in ways that you’ve so thoughtfully mentioned.

Before we finish do you think you could maybe talk a little bit about Steam Clean, a work about bathhouse cruising you made in 1990 and the way in which that particular work attempted to put into action some of the ideas that you had that developed out of making Chinese Characters?

Perhaps, I can briefly frame that by saying that Steam Clean was one of the Safer Sex Shorts produced by Gregg Bordowitz and Jean Carolmusto, the producers of the GMHC Living With AIDS TV series for Gay Men’s Health Crisis (the AIDS activist organisation founded in New York in 1981). By contrast with the other shorts, which were made with identified at-risk groups you authored the work by yourself as a consequence of being an Asian video artist who had already made work about pornography and the pornographic representation of Asian men.

In Steam Clean a young man of East Asian heritage cruises the bathhouse and as he looks into different booths he encounters different reactions, indifference or hostility, until he meets the friendly gaze of a young man of South Asian heritage. The two men practice safe sex with condoms and in the essay Shortcomings you talk about the importance of having the East Asian actor actively cruise and then ‘top’ as a kind of representation wholly absent from North American porn.

Richard: I think in some ways, Steam Clean is a development of or an addendum to Chinese Characters, where instead of the Asian-Black erotic relationship of Chinese Characters, I have an ‘intra-Asian’ or East Asian-South Asian one, and again that’s something else I’ve written about.

Having moved from Trinidad where the largest single ethnic group are from the Indian subcontinent, and then having gone to high school in Ireland, with close relations to Britain, where Asian commonly refers to South Asian and then living in Canada, where one would say Asian to mean Eastern or Southeast Asian, I’ve always been interested in these kinds of geographical essentialisms.

Or the way that race categories are seen on the one hand to be self-evident, but on the other hand, are very, very contextual. Because I had been asked to make something for ‘Asian’ communities, that was something that I wanted to explore. I knew that in the American context at that time, there was little thought for South Asians in gay representation and that’s one of the reasons why I included Richard, the South Asian actor in Steam Clean, (who’s actually Trinidadian).

Similar to the way that I wanted to celebrate the sexually explicit image in Chinese Characters, in Steam Clean I wanted to celebrate the site of the bathhouse, which in the U.S. context was blamed for spreading HIV. In the Canadian context, there was a different kind of approach in terms of public health which saw these places as sites of possible pedagogy. Seeing that people were going there to have sex, instead of saying: ‘No, you can’t have sex,’ the Canadian approach was to keep the site open and to use it to for safer sex education. Safe injection sites operate on similar principles.

Conal: It’s also worth mentioning that in the Canadian context of the 1980s, the bathhouse as an activist site had an added association because of the 1981 Toronto Bathhouse Raids, when the Toronto Police raided four bathhouses and arrested nearly three hundred men, the largest number in peace time. This was a moment that re-defined gay liberation in Canada and prompted protests against and resistance to police violence, surveillance and intimidation, or more broadly institutional homophobia and homophobic social attitudes, which in turn catalysed the development of AIDS activism in Canada.

Richard: Oh, absolutely, yeah. You’re reminding me of this, but of course, the bathhouse raids would have been another context too. In Toronto that is our Stonewall, but personally speaking I was going more to the bath house in that later period.

I became fascinated by these types of heterotopias, you know, places in which when people shed their clothes, to some extent, with the exception of race or body type, etc., one sheds certain kinds of class privileges. Not that they became completely invisible, but there was a certain way in which, when everybody’s wearing a towel, somebody who may hold power because they’re a judge, a doctor or a financier, compared with someone who may be 21, has no job, but has a great body, sees that power shift.

How these power imbalances come back to the body and how these communities are structured differently was really fascinating. I had the pleasure of going to a couple of bathhouses in the states like in Chicago, or New York at the end of that famous time when for instance Bette Midler would sing at The Continental. I never went to the Continental but I remember I went to a bath house in Chicago at the time I went to the second Third World Lesbian and Gay Conference in Chicago where there was a huge dance hall in the middle and all these men dancing to disco in towels!

Conal: Sounds truly fantastic.

Richard: That was the last gasp of that culture, which I really missed, though in which I never fully participated as I think I was probably too shy to have sex with anyone anyway!

Conal: It’s important to acknowledge as you have that these were social spaces and pedagogical spaces as well as places where people could have sex or where public sex happened. I think it’s also worth saying that the representations of these kinds of spaces in your videos and those of your peers very much pushed back against the conservative censorship laws against pornography in Ontario throughout these years, so it was a kind of auto-critique in a way. Was your work ever censored or removed from exhibition as such?

Richard: Yeah, I mean, I was part of that anti-censorship movement with people like John Greyson but do you mean Chinese Characters or Steam Clean?

Conal: Either/ or…

Richard: Oh, Chinese Characters had a brief national scandal. It was bought by the National Gallery of Canada and was exhibited in the opening exhibition of the new National Gallery in Ottawa. I think someone went to the gallery saw the show and complained, articles and opinion pieces were written in the newspapers and there were calls to have it removed but the Director at the time Shirley Thompson was an amazing woman who just stood firm and said: ‘No, we’re not getting rid of this!’ And it therefore never came to censorship because the gallery refused to back down.

Conal: What a fantastic tale and as much as I hate to bring our conversation to a conclusion I think the survival and endurance of your work is a very suitable way to end, Richard. This has been a splendid conversation and it’s been so valuable to the project to discuss Chinese Characters and to expand on the themes, content and production of your works at this particular moment. Thank you so very much.