The road made to walk on Carnival day

Constable I don’t want to talk, but I got to say

– From The Road (1963), by the Lord Kitchener

In May 2021 I attended an exhibition, a group show of work by Black British women and non-binary artists, at a gallery in central London. It was my first time visiting a gallery—indeed, any public cultural space—since the first lockdown had been announced, just over a year before. Among the pieces on display were several moving-image works, including Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical (2019) by Rhea Storr, an exploration of the Carnival celebrations in the Bahamas, known as Junkanoo, as a site of Afrofuturistic performance and cultural resistance that lies beyond the traditional coordinates of Afrofuturism, located within a particular African American experience.

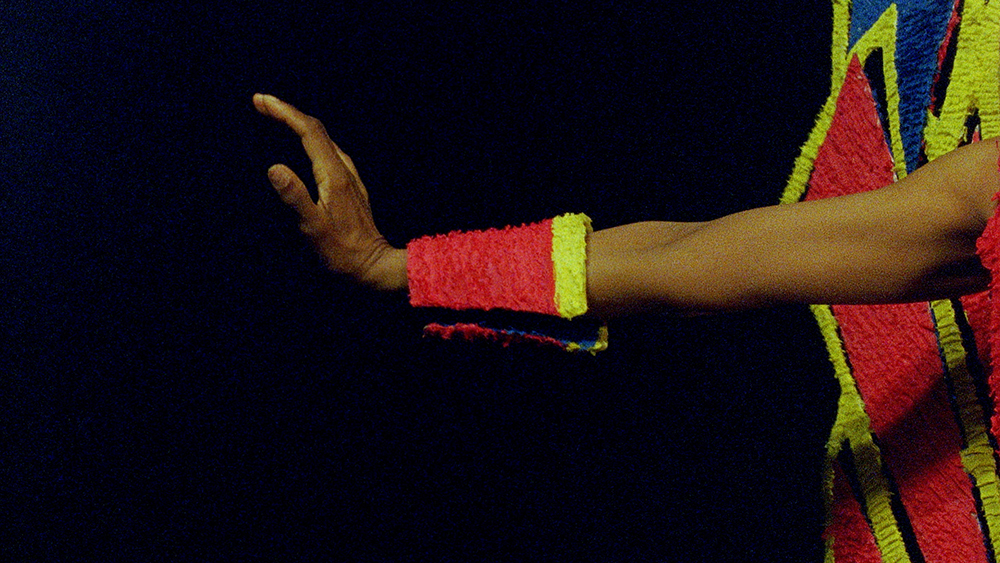

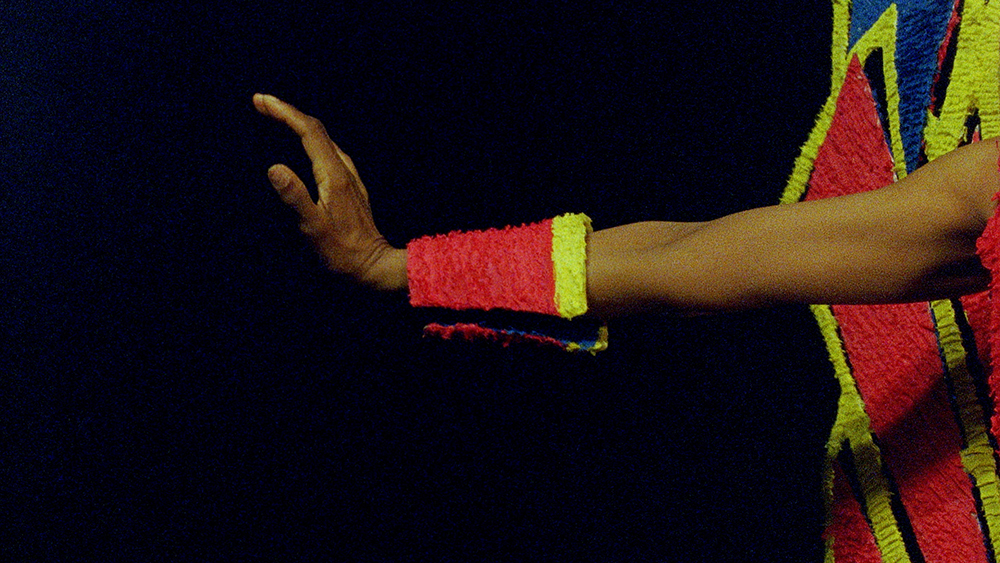

I had seen Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical several times before and was, in fact, in the process of curating it in a shorts programme as part of an upcoming film festival. Yet I’d not had the opportunity to see it projected onto a big screen—in this instance, one large wall of the gallery. The by-now familiar glitchy mix of 16mm and digital footage showing Junkanoo preparations and celebrations, of colourfully costumed groups parading in joyful formation through the streets of Nassau to the accompaniment of live brass bands, compelling voiceover narration and testimony interweaving on the soundtrack with a layer of “spacey” samples and a separate bass-heavy score beneath, and on-screen text declaring SPACE AIN’T THE PLACE. THE IMAGINATION OF THE BLACK RADICAL IS HERE. deployed like a series of perfectly timed detonations all came together to assert themselves anew on my senses, and, overcome, I began to cry.

Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical, Rhea Storr, 2019

It would be easy, too easy, to ascribe my reaction to this viewing of Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical to the admittedly stultifying experience of almost fourteen months of the enforced watching of films on my laptop. There was that, but more was happening here. There was the reminder as I looked at the crowds of mostly Black people lining the parade route and within the Junkanoo bands that the previous summer the streets of Notting Hill in London and those of other cities in Britain had been absent the usual gatherings of people, Black people, Carnival being the occasion when and where the Black presence in this country is most directly visible and asserted. (A state of affairs that was to repeat itself the following summer as the pandemic, loop-like, reimposed the many privations of the year before.)

And there was another, salient reminder, which is that over the last several years Rhea Storr has been building an impressive body of moving-image work, anchored in the defiant materiality of analogue film, and proceeding outwards from her own layered identity as a mixed-race woman, of English and Caribbean (specifically, Bahamian) heritage, who is from rural Yorkshire. At the centre, chronologically and otherwise, of this practice is a series of key works that you could call her Carnival Trilogy: three films, of which Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical is the most recent, that investigate the art and idioms of Carnival as both celebration and protest—celebration as protest.

There is an inescapable paradox at the heart of these films. Carnival, specifically the Caribbean Carnival from which the Carnivals in Britain are descended, with its roots in African-Caribbean plantation slavery, has traditionally hinged upon ideas of transience and impermanence, of fleetingness. Carnival is cyclical, seasonal in nature. It takes place once a year, over a few short days; all of the months of intensive labour that go into its production, from the creation of the costumes that the participants wear to the composition of the music that they perform to on the streets is intended for that year’s edition of the Carnival and that year only (the licence to occupy the streets, as the Lord Kitchener observes in his classic calypso, similarly for a limited period but no less important for all that). No costume, however elaborate, or no song, however catchy, is to be used again.

Junkanoo Talk, Rhea Storr, 2017

This is very much the point, or a point of Carnival, a popular form of street theatre that also partakes of other arts; not unlike cinema, a renaissance, collective art. Rhea Storr’s analogue films, while not directly invested in problematising the notion of Carnival’s transience, by their very nature pass ironic comment on the idea of Carnival as merely colour and movement, gyrating bodies in skimpy costumes. Storr plays with these ideas in Junkanoo Talk (2017), a provocative deconstruction of the visual and sonic languages of Carnival celebration. The film begins by quoting James Baldwin on his duty as a writer vis-à-vis his life experiences, an epigraph that could stand for the filmmaker’s own attitude towards Carnival: “It is really quite impossible to be affirmative about anything which one refuses to question—one is doomed to remain inarticulate about anything which one hasn’t by an act of imagination made one’s own.” Almost forensic in its micro-to-macro focus, and in its use of repetition to examine costume, performance, and the human body, Junkanoo Talk still yet refuses to fully frame that (non-white, female) body, abstracting it to create an opacity meant to subvert a traditionally exploitative gaze, as well as simplistic and dismissive readings of Carnival’s complicated politics.

Storr enacts a reversal of sorts in A Protest, a Celebration, a Mixed Message (2018), the most directly autobiographical film of the Carnival Trilogy. It pivots on a pair of seeming dualities/dichotomies. The first is between the urban and the rural, as seen in the Leeds West Indian Carnival and the surrounding Yorkshire countryside. The second is between Black and white, seen in the mixed-race and costumed body of Storr herself, which comes to occupy the frame in full, the author firmly holding her camera’s gaze; a validation of her right, not just as a non-white but also a mixed-race woman, a Yorkshire woman at that, to take up public space, to celebrate and to protest, in both urban and rural settings.

A Protest, a Celebration, a Mixed Message, Rhea Storr, 2018

More recently, Storr has interrogated her own interest in celluloid, and furthered her concern with investigating the exploitative/exoticising gaze upon performing Black and mixed-race women’s bodies in Madness Remixed (2020). A found-footage work based on the iconic figure of Josephine Baker, the film makes two sets of productive associations: between the fetishisation of Baker’s body and the filmmaker’s own analogue fetish, and between Baker’s infamous banana skirt and the work of Black labourers on banana plantations, in the Caribbean and elsewhere in the Global South.

Through a Shimmering Prism, We Made a Way (2021) is Storr’s newest film. The poetry of the title may have something of Jonas Mekas about it, but it actually echoes the name of a book by Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. This polyphonic work, her longest, is Storr’s most considered meditation on the Black diaspora and collective identity—the Door of No Return is the point in Senegal through which millions of Africans passed on their way to the Americas to be enslaved. Shot both in London and Nassau on undifferentiated black-and-white Super 8mm film, the film further suggests diasporic connectivity and immediacy through a quietly audacious editing strategy that collapses space and time. Here is there and there is here, with all the benefits and complications that entails. Storr’s camera bears witness in both places to public squares, traditional Carnival parade routes now empty due to the pandemic. But they will be full again. As one of the three women who make up the “We” of the film’s title says in counterpointing voiceover: “They dictate the ground, we dictate our presence.” The road made to walk on Carnival day.

Jonathan Ali is a film programmer and curator. Born and raised in Trinidad, he now lives in London.