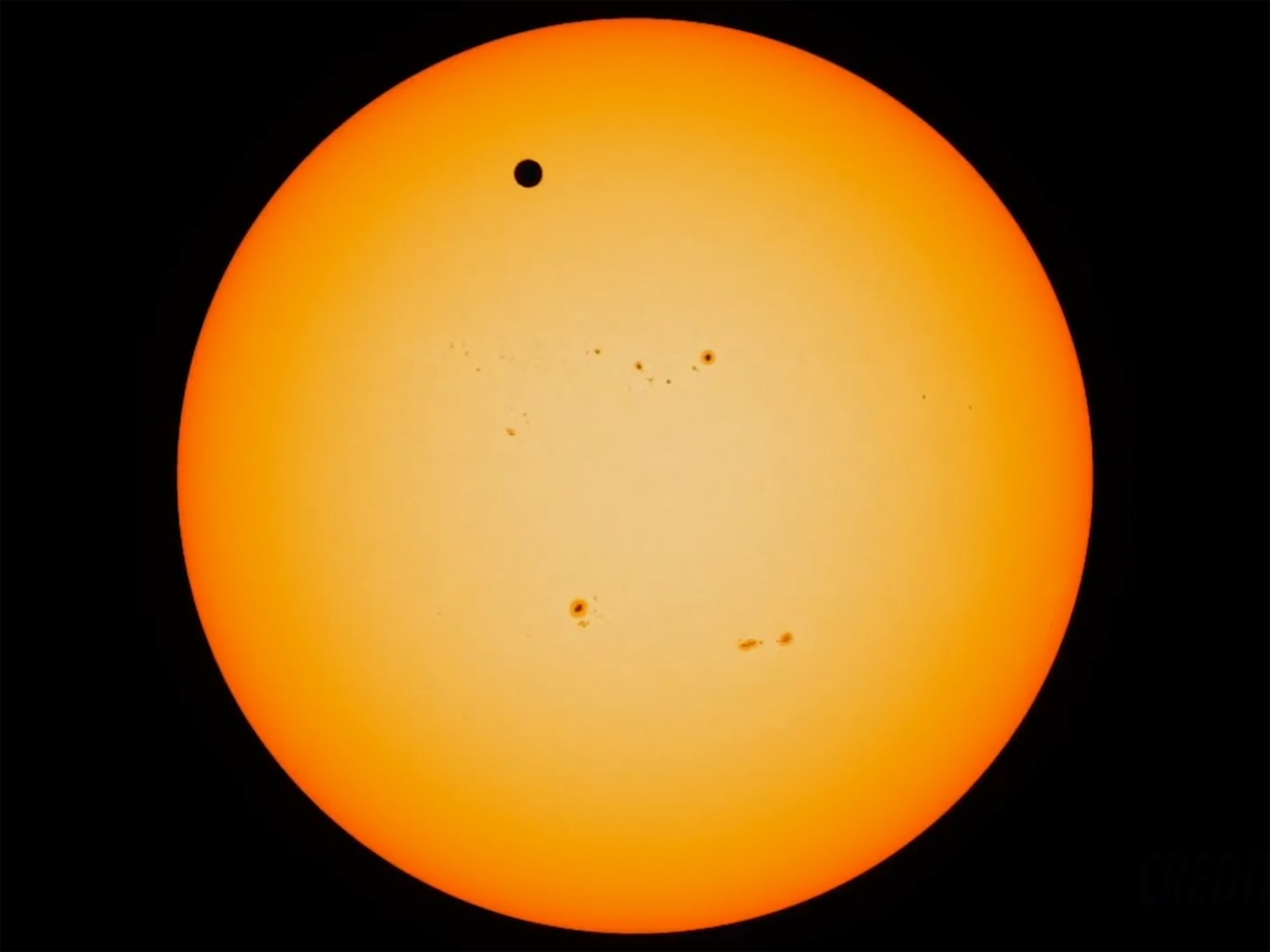

I still dream about the shade of yellow in P. Staff’s On Venus, the yellow of radioactive piss, corrosive light, the color of jaundice, as much the sun as the moon. Wallace Stevens called yellow the “first color,” but for Staff it is the last, the final color at the end of the world, too late, post doom, now what. A more romantic artist might balloon this into a cathartic break, a crack in the world that everything falls through. The primary feeling of On Venus, though, which was on view at Serpentine Galleries November 2019 – February 2020, was that the yellow light was awake, breathing, something that held you. I walked through it and became infested, but gently. It soaked me like a liquid, warm and calm. I had the impression that if I were to slice my wrists open, a glowing yellow blood would trickle out, matching the color the light had made of my skin. I didn’t want to stay long in the dark room at the center of the gallery—which showed a 13-minute video of the various animal brutalities (snakes cut open with scissors, a dying chicken’s eye staring flatly into the camera) that motor our society’s agricultural and medical industrial complexes—because I didn’t need to, the images in there followed me out. I was irradiated by them. Staff has said On Venus “is about how to live with violence, continuous ambient violence all around us,” and I think the liquid light that glared through it, violent but soft, still sheathes me, a warning, and a bath, and a sky, and—. Alexander Theroux wrote of yellow: “It is the color of butter, arsenic, sponges, candlelight, starving lawns, translucent amber, and cathode transmission-emitters in electrical chassis wiring. It represents wisdom, illumination,… the hue of confessors,… ripening grain, eternity, and the gates of heaven.” Maybe I felt a special recognition in finding that Staff had drenched their show in yellow. It’s my favorite color: Because it can be so many different things—toxicity and illness and gold and honey—and still be called a pastel. It’s the color that threatens acid rain despite, or because of, its softness. Yellow is the most versatile of all colors, which can tilt it toward vagueness, unlink it from meaning—this is why it’s so cool. Unlike red or blue or purple or green, yellow has no dominant allegiances (it’s not the color of blood or Mary or royalty or envy), only disguises, mutations. I once made an entire show about the color yellow, during a period of three months in which I wore only yellow (a feat for a goth). The witch I was working with at the time told me to visualize that I was inhaling yellow light, that a beam of it was shooting out of my third eye. She wanted me to heal. But not too hard, not too fast.

When I walked into On Venus last year, stepping out of a cold London night in November, I said, “of course” out loud as Staff’s yellow slithered into me and started to hum. Yellow’s power is slippery: in Staff’s work it was not a big fist pounding a table, but a hand sliding around your neck and pulling you in. On the surface, it was the color of Venus, her burning sulfur, but this asphyxiation quickly became political. It was the air we all breathe that is also suffocating, quickly for some, slowly for others. Yellow also appears in Staff’s 2017 work, Weed Killer, as part of its vivid palette—ultramarine blue, cerulean, vermillion red—created through high-definition thermal imagery. The irradiation of Weed Killer is one of contamination, also slow and seeping and permanent: the film is propelled by actress Debra Soshoux reciting a monologue from Catherine Lord’s memoir The Summer of Her Baldness, which describes the annihilating effects of chemotherapy on the body. She begins by noting it’s “not quite right” to say that she feels like shit or has the flu: “The flu is like something is borrowing nourishment from your body. You don’t want to make the loan but you can. This is different. Something has broken into your body with murder on its mind.” Yet she needs the chemotherapy, paradoxically, in order to live. Over the course of Weed Killer, this intruder breaches and penetrates and plunders her body without mercy, and then it coils up and sleeps there, home. I think of the pharmakon: the poison that is also the cure. I wonder if the pharmakon is inherent to the body itself—that the body gets depleted simply by doing what it is meant to do, that pain rushes into your joints after dancing, that your teeth get chipped from chewing, that seeing and looking and watching weakens your eyes. Sometimes I think that the history of the world is the history of trying to cope with this thing called the body.

Weed Killer, P. Staff, 2017

In interviews Staff strategizes Venus, “a sister planet to Earth that is completely inhospitable,” as a metaphor (metonym?) to describe a primary alienation that “the world around me is normal but things are absolutely not okay.” About the conceptual framework, they called On Venus “a parallel form of life, a parallel space of not quite being alive, not quite being dead, a sister planet, a sister reality.” This idea, throbbing like an artery, animates all of Staff’s work: it’s the premise that dysphoria is an ontological condition. It’s like their yellow: it’s not blazing and loud, but oozing, sinking, it snuck into my dreams. It’s the suggestion that dislocation, rather than being an inciting event, is simply the default, because to be located—by what, and for whom—is a rare privilege, afforded only a few who’ve conformed to a world not made for most of us. Staff has called it a lens: “If my body is the prime mediator between some sense of myself and the outer world, then it’s an inherently dysphoric lens.” In this quote (from an interview with Claude Adjil), Staff is speaking specifically about gender dysphoria, but the next sentences expand:

It could also be like living in a nation state that’s actively murdering, bombing, slaughtering others, elsewhere. It could also exist in relation to being a ‘free’ person knowing that there are ever more imprisoned people in this country.

The “also”s here are what catch me, braid me into an atmosphere that I recognize—I could add to this list ad infinitum. So could you. It’s the weather of our world, a climate we cannot control, we can only hope to cope with it, we can bring an umbrella if it looks like rain but we cannot stop ourselves from getting wet. In an interview with CAConrad, Staff said of On Venus: “I try to use the idea of being on venus as a way to describe a slow but perpetual or consistent state of being, a sort of pushing through this liquid, a sort of shorthand to or for describing parallel forms of life, dispossessed living, or ulterior states of near-death, non life, non death.” In other interviews, they repeat these three phrases—near-death, non life, non death—and I think that such states, rather than being bloodied or rotted or putrefied, are flavescent: clear, cautionary, well-lit.

P and I first met one winter in Minneapolis, when we were both residents with FD13. We stayed in a place that was called “The Cloud House” because of its all-white interior and frosted windows. I remember waking up my first morning there and smelling P’s perfume in the air. At FD13, Staff began work that would become the 2018 film Bathing, which depicts a lone dancer in an empty warehouse, moving in and out of a shallow basin of water. The dancer stumbles and lurches, sometimes bent over and growling like a dog, under fluorescent tube lamps. There is the occasional flash of an image of oil, the U.S. border patrol, a dog playing at night, but the palette of the dancer is soft, pale, her cheeks flushed pink. The choreographic language of drunkenness hints at questions about cleanliness, as the water becomes more and more stagnant, eventually to be pissed in, and despite the dancer’s thrashing and flailing, she is somnambulant, this is not rage or lunacy, this is just some evening somewhere.

Bathing, P. Staff, 2018

In astrology, the asteroid Chiron is said to represent one’s greatest wound, a wound that will never heal. The only respite from Chiron is that one might heal others through the knowledge the wound has given. In Ancient Greek mythology, one of the stories finds the immortal centaur Chiron pierced by a poisoned arrow, but he cannot die because of his immortality, so he willingly takes the place of Prometheus, who is being punished for stealing from the gods, chained to a rock, his liver eaten every night by an eagle. Prometheus has his own wound that will never heal—he and Chiron are sisters. With his sacrifice, Chiron is granted reprieve from his pain and allowed to enter the underworld; in some endings, his body dissolves into stars to become a constellation. I tell my astrology clients this story, so I can speak about healing and sacrifice and fate, but I also tell them that the definition of the word “kairos” in Greek is merely “weather.” The Chiron in your natal chart will show the wound of your life that will never heal, but like the weather, it is your background, your atmosphere, the air you breathe, you can lean against it, its rhythm, you can bring an umbrella. In some clients, this mitigates the shock of being told that your greatest wound will never heal. In others, though, hearing about Chiron is validating—I knew something was wrong this whole time! I imagine that if I were to tell P. Staff about their Chiron they’d already know about it, they’d probably laugh and shrug. Of course.

Perhaps the recognition of yellow that zapped me in On Venus is because I understand gender dysphoria as someone who is genderqueer, or how I’m imbricated as a disabled person into the capitalist medical-industrial complex, or perhaps it’s because I’m a citizen of a country who proclaims itself to be the greatest in the world, while it disappears people from the streets of its cities, locks children in cages, and supports the swell of wealth among billionaires while its people starve and suffer and die during a pandemic. This list could go on. It is merely the weather of our world, of our time. Chrome yellow is the color that can be seen at the farthest distance on earth. Subtitles and captions are yellow because, over the course of becoming blind, yellow is the last color you can see.

In Ancient Greek, the word “kairos” had a different meaning: it referred to a kind of time. Rather than chronic time, kaironic time was cyclical; something like the right moment; a unit of fate. Unlike chronic time, it cannot be measured, it has to arrive when the time is right. How this shifted over the centuries to mean the weather is something I wondered about while moving through On Venus. As I’ve revisited Staff’s work to write this text, yellow has crept into my life again: last night I made dal with red lentils (which turn yellow when cooked) and turmeric, I painted my nails gold, I read the news that Beirut is in a state of emergency after two explosions wounded more than five thousand people, but the hospitals, already over-capacity with COVID-19 patients, had to treat them on the sidewalk. I watch the death toll rise with Jeff Bezos’ income. I think of the first color that is also the last. The color of illness and saints. Fate that is simply the weather.

Johanna Hedva is a Korean-American writer, artist, musician, and astrologer, who was raised in Los Angeles by a family of witches, and now lives in LA and Berlin. Their new book, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, a collection of a decade of work, was released on September 2. Their first novel, On Hell, was published in 2018. Hedva’s work has been shown in Berlin at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Klosterruine, and Institute of Cultural Inquiry; at The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; Performance Space New York; and the Museum of Contemporary Art on the Moon. Their album, Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, will be released in November.