The question I am asked more than any other is ‘how do works get into the LUX Collection?’. This is a critical question in LUX’s history, relating to the very foundational principles of our founder organisation, the London Filmmakers Co-operative (LFMC), and something we continue to discuss and reflect on as an organisation to this day.

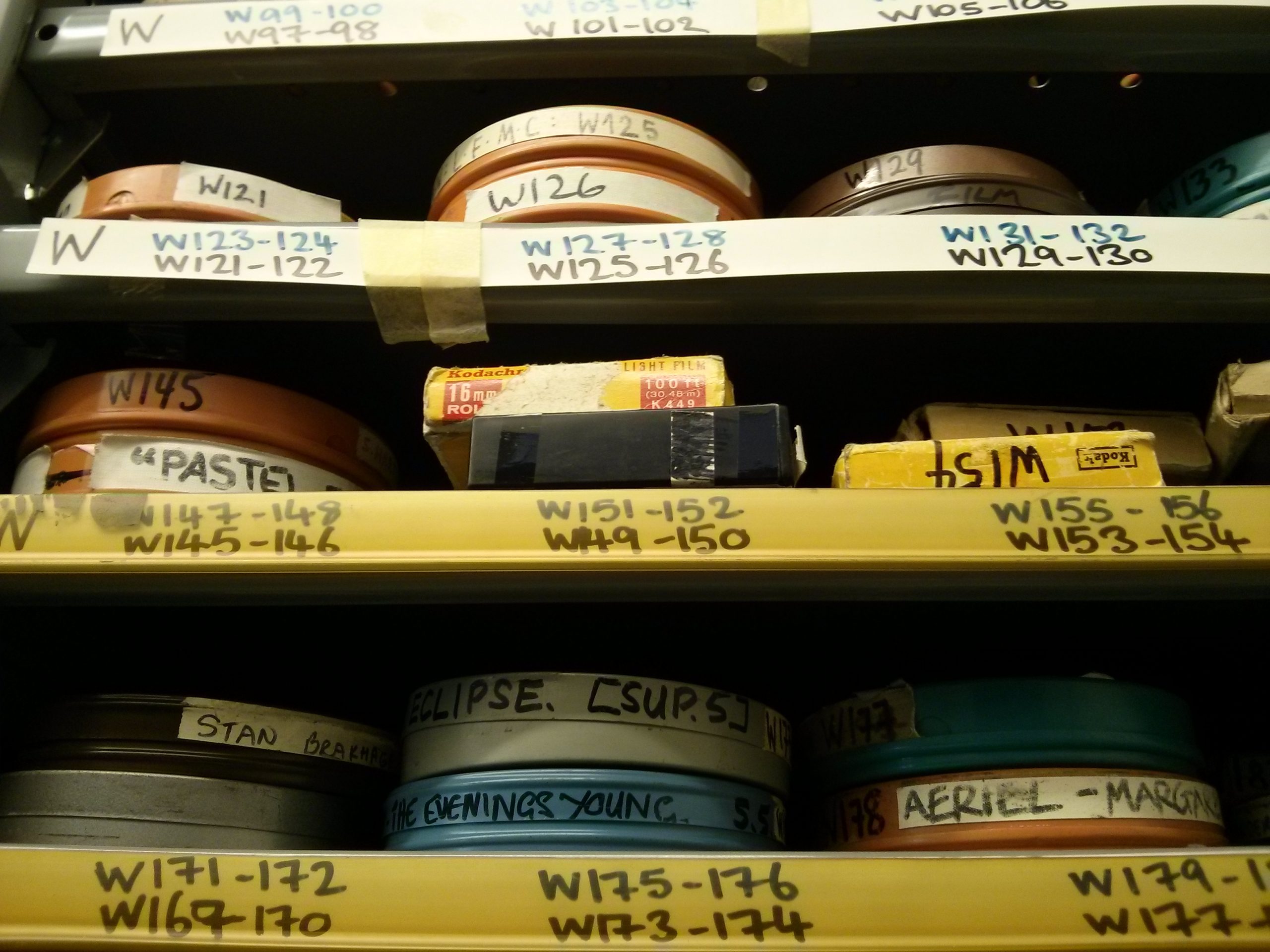

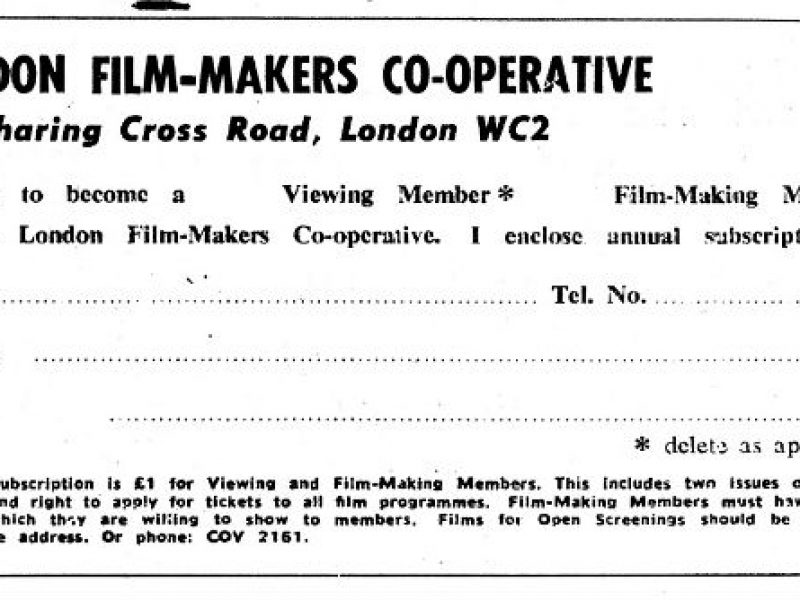

As a co-operative, the LFMC was committed to an open access policy of acquiring work, whereby any filmmaker could deposit a film in the collection and thus become a member. This democracy was balanced with a principle of non-promotion whereby no work would be promoted above any other. Filmmakers would simply provide a catalogue text, the films would sit on the shelf until asked for and the distribution organisers would simply administer with the assumption that the filmmaker would do the promotional work themselves. This system allowed for the collection to develop in sometimes weird and wonderful ways with no guiding principles beyond who was drawn into the gravity of the organisation. They may have shown their work at the LFMC, used the laboratory, been an international filmmaker passing through town or were friends/students of existing members. Of course, in the 1960s and 70s there was relatively little indigenous artists’ filmmaking in the UK, so the collection was relatively small and manageable. In 1976, our other founder organisation, London Video Arts (LVA), was established with similar principles in terms of building an open-access collection. Like film, at that time video was very much in its latency so there was not a huge amount of work being produced. However, unlike the LFMC, LVA was not a co-operative, thus it did not have the same principles of democratic non-promotion. Also, because it lacked its own exhibition space, proactive promotion and advocacy for the then newly defined ‘video art’ was a key activity for the organisation, with the open-access policy really set by funder demands.

Fast forward to the present day and things have changed significantly. As far as I am aware, the idea of open-access submissions to the collection stopped in both organisations sometime in the early 1990s (see Julia Knight & Peter Thomas’ excellent book Reaching Audiences, Distribution of Alternative Moving Image for a detailed history). For some, this was seen as a betrayal of the founding principles inspired by a democratic desire to resist the perceived competitive hierarchies and gatekeeping of the art world. I always assume this change was born of rationalism, that artists’ film and video had grown exponentially and there was now so much more of it. Realistically, this was more than the organisations could effectively manage, as the collections were already becoming large, unwieldy and difficult to navigate. As the collections gained more visibility and a de facto status as the only significant collection of artists’ moving image work in the UK, this also raised the important question of how representative they were. Was it really enough to rely on the gravity of the organisation to build a collection? How about all the artists who did not have any connection to it? It was important to develop a more proactive system that could be mindful of the limits of the collection and actively address major ellipses of both artists and works.

The echoes of open-access remained in place as the organisations moved to a system of open-submission, that is that if work could not be submitted directly into the collection it could at least be submitted to the organisation(s) (as LFMC and LVA/LEA merged in 1999 as the LUX Centre then finally LUX) for consideration. Every 3 months the organisation would have an open call for submissions for distribution, and every 3 months we would receive 100+ works to consider. This was a hugely unsatisfying experience as we were both overwhelmed and unable to give each work the consideration it needed. Ultimately, we ended up rejecting a huge amount of work on this basis, which felt both in bad faith in terms of the principles of openness and ineffective in terms of really understanding the intentionality and context of the works. With this in mind, we stopped having open submissions for distribution acquisitions and instead established a rotating panel of internal and external advisors to scout for and propose artists who we would then consider in quarterly meetings. Our external advisors have, so far, always been: an artist who is already represented in the collection and an external curator, who both serve for one year. Advisors and LUX staff bring proposals to the group to consider and circulate links and information in advance, which is then discussed at the advisory meeting. The obvious first criteria for consideration is that someone on the panel should know about the artist and be enthusiastic about their work. We would never pretend that subjectivity does not play a part in this process. That, of course, raises the immediate question of how LUX staff or advisors know about an artist’s work? It is possible to send us information about shows and screenings, as we are constantly working proactively to discover new work. Every month, we also organise free one-on-one artists’ sessions where you can meet LUX staff and discuss your work with them.

In terms of our criteria now, we are looking to represent the breadth and diversity of artists’ moving image practice in the UK both historically and contemporaneously. We are looking for artists who have a body of moving image work as part of their practice, and have received a degree of critical attention and peer recognition for their work. We are looking for work that is also ‘distributable’; by that we mean work that is not over-reliant on specific contexts (physical and/or cultural) for its legibility. Finally, we are looking for work that fits within the narrative of the collection (again a rather subjective definition), and this includes historical works which for whatever reason did not enter the collection at an earlier point. We usually automatically distribute new works by artists we have an active working relationship with already, although if this relationship has lapsed, as with some older works in the collection, then we will revisit this through the acquisitions panel.

Historically, the collection was international as it was formed in a time when works were less mobile. These days, we focus mainly on UK work and signpost to our international sister distributors (there are a number of national distributors in other countries many of which also distribute UK work). We do distribute a small selection of international contemporary artists who work predominately in the moving image and have a close affinity with the other works in the collection and LUX’s wider work. Ultimately, though our resources are limited, each new artist in the collection is a new relationship, and to be in good faith about our ability to work effectively with them means we have to make difficult choices and are unable to be as open to new work as we’d like (to put this in context, a commercial gallery might represent the work of 10-20 artists, LUX currently represents the work of about 1500). It is important to note that distribution is not by any means the only way we work with artists, and nor is our other work limited to artists and works already in the collection.

As I said at the beginning the acquisitions process is always evolving, shaped by the ideas of the people currently involved and the ever-changing demands of representing the wider culture of artists’ moving image production in the UK.

Benjamin Cook, LUX Director

December 2018