A note: I first saw Idrish (ইদ্রিস) as part of the programming team of Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival (BFMAF) where we programmed it for the 2021 edition. Some of the contextual information and excerpts of conversation found below come from discussion with the filmmakers and programmers during this time, particularly this recorded conversation with BFMAF 2021 programmer Alice Miller.

I have been trying different ways to open this essay about Idrish (ইদ্রিস). Each direction I write it in seems to tip into description, history, biography. The openings I write sometimes take me closer to what the film is about, but further away from what it asks me to do.

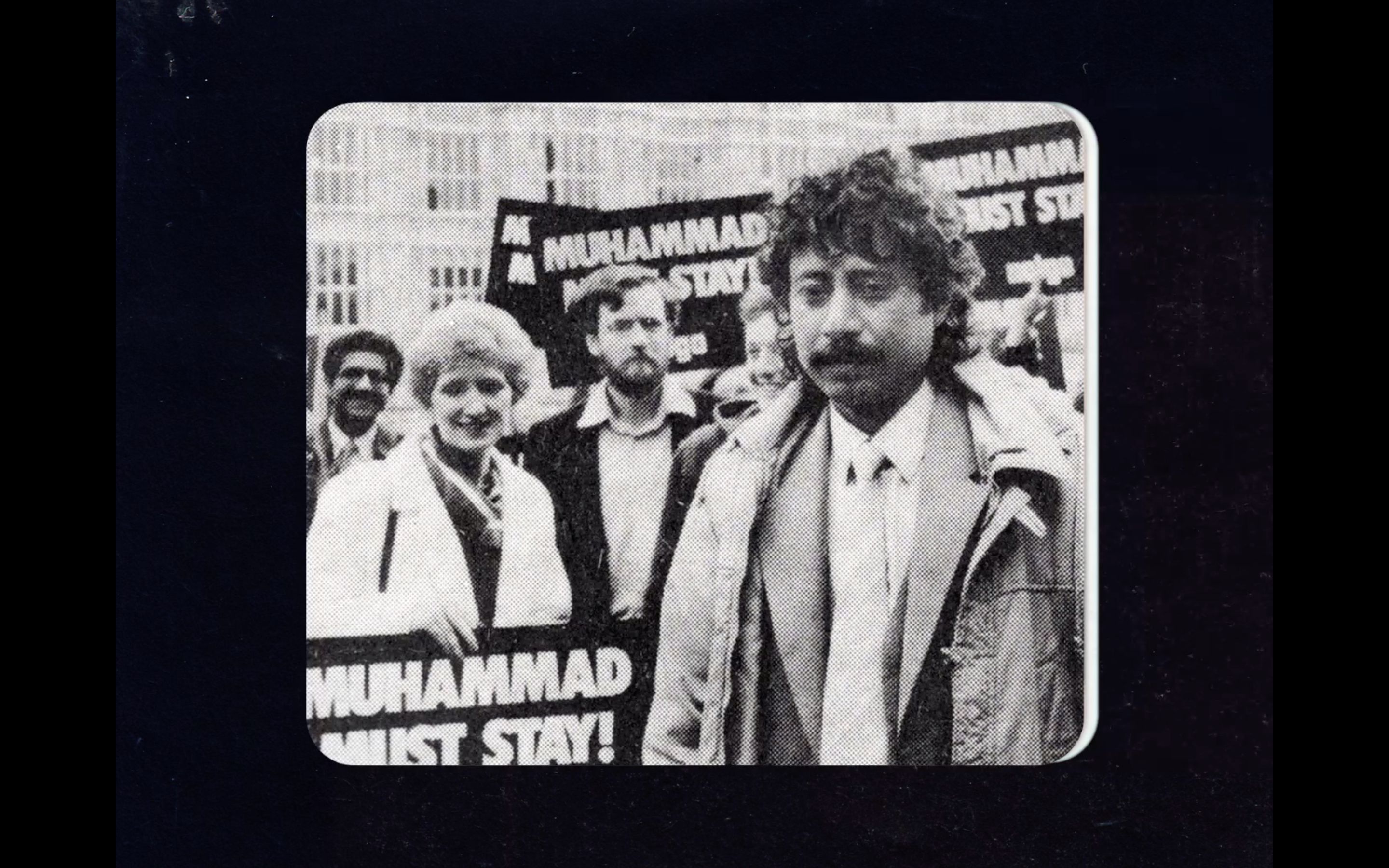

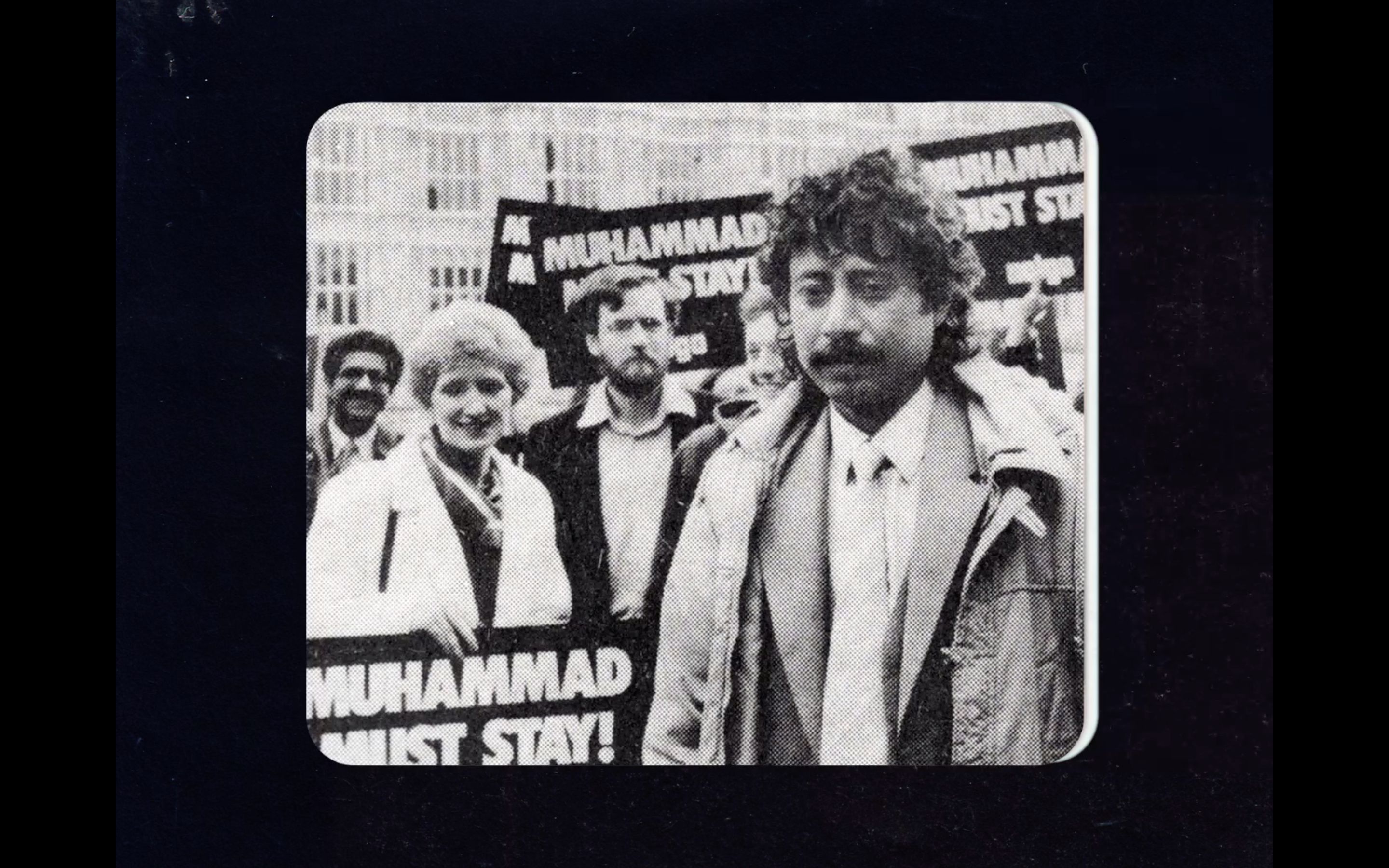

Idrish (ইদ্রিস) is about a moment in Birmingham when trade union, anti-deportation and anti-racist organising against racist immigration policy in the post war period assembled around the anti-deportation fight of one man. I want to say that these things are brought to life through a collage of image, story, sound but also through relation. I want to say that the film is rooted in a friendship instigated when Muhammad Idrish and Adam Lewis Jacob met through Lewis Jacob’s research into the Birmingham Trade Union Resource Centre archives, which had preserved some films Idrish had made in the 80s and 90s and further deepened when Idrish asked him to make a film about his story and Lewis Jacob invited sound designer Claude Nouk to collaborate on it. The film is forged through a collective assembly of causes and stories, in the past and in the present. Idrish’s deportation and the campaign NALGO Trade Union developed around it is central to it, but through the filmmaking collaboration – and of course because of the ongoing unresolved issue of the UK’s hostile immigration policies – other synergies emerge. Just after joining the collaboration the UK government attempted to deport Nouk. And one day as the film is almost complete, just outside Lewis Jacob’s home on Kenmure Street in Glasgow hundreds of protesters gradually gather throughout the day and surround a Home Office van attempting to deport an immigrant family that lives on the street. Through these connections across generation, time and experience a warm and intimate portrait of Muhamad Idrish’s life of political activism becomes a film in movement and about movements, interested less in one chronology but rather multiples, reaching outward from mere biography, or portrait, towards the idea of Idrish as a rallying cry, that gathered different people around a shared desire to change what they saw as broken in the world.

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

The film begins in 1921, 1983 and 2020. Scenes from Lewis Jacob and Idrish’s 2020 trip to Bangladesh are overlaid with a recitation of Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Bidrohi (The Rebel / “বিদ্রোহী”) a revolutionary Bengali poem from 1921. Kazi Nazrul Islam is part of a lineage of Bengali radical activism, a fierce opponent of the British, a young man who, like Idrish, was moved by witnessing injustice to raise his voice in anger. As a young boy, Idrish often heard his uncles recite this poem, learning the cadence, emotion and rhythm of its words long before he understood their meaning. Through this recitation we get a sense of both the pain but also the catharsis of coming to know, the moment of political education when we metabolise a lesson Idrish will dedicate his life to passing on to others facing state violence — “you are not one”.

Just as this revoicing invites us to think beyond the individual story of Idrish, its propulsive timbre invites us to enter the film through bodily memory, vibration and affect of voice, rather than simple chronology. Nouk’s sound design is introduced here as a form of memory work. Taking sounds that were actually present such as the chants and the percussive beat of people’s feet marching on the ground, Nouk builds the aural atmosphere of the film with an attentiveness that reminds me of Audre Lorde’s essay Poetry is not a Luxury (1985) specifically the line “There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.” Reassembling and remixing archival sounds, the aural landscape is undoubtedly rousing and activating, a call, but it is also a form of loving echo — a direct inversion of the state indifference that is at the root of the sounds in the archive.

The story of Idrish’s journey to the UK and his journey to activism is in one narrative, a story of responsiveness to another kind of call — that of post war ‘welcome’ offered by the UK to its ‘commonwealth’ ‘citizens’. As a young student, Muhammad Idrish was drawn by that call, travelling to the UK on a British Council scholarship to attend Bristol Polytechnic and later work for Dr Barnados.

Believing in the generosity of this call, gathered by its invitation, he built a life, fell in love and married an English woman, subsequently applying for ‘indefinite leave’. For two drawn out years immigration authorities scrutinised his life and his relationship, assessing his suitability to stay. After the breakdown of his marriage, those same authorities moved now with speed to threaten him with deportation, certain that his marriage — despite domestic divorce law which specified couples must live apart for two years and be assessed by a judge or magistrate before a marriage could be deemed to be ended — was in fact over, in effect forcing its ending.

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

The film turns these state methods to exclude and divide — the collapsing of the parameters of civic and social bonds, and conditional expansion of borders and time — designed to weary, isolate, and obscure justice into another practice. Through the acts of solidarity recorded by the film, and in the collaboration between Lewis Jacob, Nouk and Idrish, past, present and future are collapsed in productive, transformative ways, opening up the possibility of thinking beyond the visual and aural borders around objects and scenes and situations and archives that we see throughout the film.

In the voice of the younger Idrish who retells his experience of marriage breakdown and then deportation is both pain and conviction. Hearing both in his voice makes me think of Gargi Battacharya’s recent writing on heartbreak and its connection to revolutionary consciousness. After I watch the film, I listen to the voice of Idrish in conversation with Nouk and Lewis Jacob last summer. In it Idrish brings to life Battacharya’s idea that “the brokenheartedness of revolutionary consciousness requires a redirection towards the collective.”

“You suddenly realise how powerful it is, all these people shouting your name or protesting on behalf of you, or what is happening to you, that was very powerful, it made me the man I became later on. If somebody else can do it for you, then you have a duty to do it for others. That message came to me through that sound that I heard on the march.”

This is what I meant when I called Nouk’s sound design a form of memory work. I don’t mean to romanticise filmmaking and what it can do, and I don’t mean to weary the word collaboration. But I want to record what I see to be the practice of solidarity that I feel in the work and in Nouk’s words when he talks about the curiosity and questioning that led to the mixing of sounds in the film:

“is this going to do justice to those moments? is this overstepping? is this muting? so I think when using some of the archival sounds that was my hope that we could keep the truth where the truth needs to be.”

In this comment about the truth and its placement, I think about self-determination and the ways that that can be enabled collectively.

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

Idrish (ইদ্রিস), Adam Lewis Jacob, 2021

At the centre of Idrish (ইদ্রিস) is a tapestry stitched by Idrish’s mother depicting scenes from her life. Made over three years, it is stitched by her own hands, recreating scenes from her own memory, with threads chosen by her, woven in the directions she chooses. The image of the tapestry works on many levels, allowing us to read the film in many directions, pulling the threads in different directions.

Like the different threads in the tapestry, in the film different images pull in different directions depending on who has made them, found them, and showed them. BBC newsreels obscures the racist underpinnings of immigration law and racist media coverage with plummy voice overs insisting that civilised and ‘liberal’ Britain remains committed to its duty to its ‘commonwealth’. In contrast films made in community, such as those made by TURC and NALGO directly address the camera in full and frank terms outlining the emotional stakes, the personal stories as well as the political goal of organising and lifting up the voices of those on the receiving end of duplicitous immigration policy.

The possibilities opened up by the form of self narrativisation in this tapestry is further amplified by Lewis Jacob’s animation. Through this technique, parts of the tapestry break free and overlay on other parts of Idrish’s life, the life that his family who still live in Bangladesh were never able to see but over which the imprint of his past will forever dance. In this dancing is an evocation of the non linearity of time as it is experienced and remembered as opposed to how it is narrativized as well as a denial of colonial ideas of assimilation and a resistance to tired tropes of ‘loss’ of identity.

Lewis Jacob has said that his approach to animation is in part rooted in a commitment to deploying the labour of attention that animation requires towards something transformative:

“Animation comes from a Fordist process, a pretty terrible way of making people work, all sat at a desk drawing cell after cell and if they are just drawing Cinderella then its self perpetuating a machine that eats itself, but if you can take animation outside of that system, put it into a new system and a new way of doing it then that can be radical and that’s why I find animation so interesting, because it represents part of something that needs to be destroyed in some ways, but it also kind of gives you the solution.”

This manual drawing and animating of the detail of a larger image like the butterfly on a tapestry or a piece of ephemera like a sticker, feels like a visual articulation of the radical act of deep listening, to truly seeing and being seen. In Lewis Jacob’s description of the labour of animation is also an insight into the quieter work of solidarity, organising and mutual aid, everyday acts done in the service of a shared goal rather than an isolated existence, small acts amplified by their repetition in the collective.

Through the labour of solidarity things can be said louder, meaning can move and travel. When a butterfly unfurls from a tapestry and moves onto the newspaper reporting on Idrish’s struggle, it seems to say, “we are here because you were there.”

As typography unfixes itself from static posters, flashing to the beat of many feet and many voices, it says definitively:

HERE TO STAY HERE TO FIGHT.

Jemma Desai is based in London. Her practice engages with film programming through research, writing, performance, as well as informally organised settings for deep study. She is currently a practice based PhD candidate at Central School of Speech and Drama thinking through the liberatory possibilities in cultural production through ideas of abolitionist praxis. You can find more about her work here.

Here to stay Here to fight is commissioned to accompany Adam Lewis Jacob’s exhibition Idrish (ইদ্রিস) at LUX (26 March – 30 April 2022).