For Memory (Marc Karlin, 1986) is a film and television programme about remembering.

It is concerned with a specific kind of social recall, which one might express (in crude terms) as that of ‘the people’ as opposed to that of ‘the establishment’. Marc Karlin, the director, had previously been a key figure in the Berwick Street Film Collective, whose films were avant-garde celluloid tributes to a class and its struggles: the Catholic Irish in Ireland Behind the Wire (1974), working women and mothers in Nightcleaners (1975) and 36-77 (1978). For Memory was a quite different project. Made by Karlin as a solo director, it is essayistic in form, and rather than focussing on a single ‘cause’, it fuses a vast array of different sources under a single but broad concept: the notion of popular memory, and the need to preserve it.

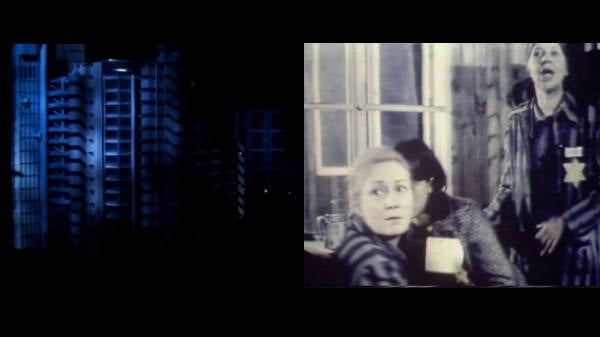

For Memory was a labour of love and fury. It was first conceived in reaction to an American dramatized television series, Holocaust (NBC, 1978), starring Meryl Streep and James Woods. The series appears to have filled Karlin with horror. Certainly, some element of this recoil was to do with his mixed background (Jewish-Russian and raised in France and the UK), but it was also much more broadly with television’s whole tendency towards amnesia, or – rather – its incessant replacement of real memories with fictional ones, its urge to dramatise and narritivise. The deadly lava of television’s ‘flow’ was, it seemed, swamping the saddest moment in recent human history.i

Karlin’s epic struggle to produce and distribute the film began in around 1977, when he was offered the chance to make a television programme for the BBC in co-production with the BFI.ii He snapped up the offer, but his progress writing the film was arduous, with extended re-writes, re-conceptualisations and attempts to wrestle his broad conceptual concerns into a manageable format. In one draft, Karlin attempted to frame it as a love story in which a man and a woman ponder over the meaning of memory. In another draft, the film was to begin with a clip from Fahrenheit 451 (1966, dir. François Truffaut) – a scene set in a dystopian future in which books are burnt and memories erased. For Memory was finished by 1982, but the BBC apparently finding it too unconventional, shelved it, before finally broadcasting it in 1986.iii

For Memory was, in its final edit, structured as a long series of profiles, interlinked with panning shots of a corporate cityscape and an epistolary voiceover:

‘A traveller once wrote: In our dreams of future cities, what troubles us the most is what we most desire: namely, to be free of the tyranny of memory; to be self-sufficient, without sense of past or future.’

The film opens with 10 minutes of interviews with two military men who were commissioned to film the horrors of Belsen in 1945. It goes on through a patchwork of episodes linked thematically to ‘memory’: interviews with elderly people suffering from amnesia or dementia in a care home; children learning Elizabethan history at a stately home; a presentation by local historian, Cliff Williams, ‘keeper of labour memories’ at the mining village of Clay Cross, Derbyshire (which in the mid 1980s would become a site of the Miner’s Strike); a long series of clips from old movies and newsreels; footage shot at a commemoration for the Levellers executed by Cromwell at Burford in 1649, with a clip of E.P Thompson delivering a speech at a Workers Education Association meeting;iv and, finally, an elderly muralist, Charlie Goodman, recalling his involvement in the 1936 anti-fascist Battle of Cable Street.

I would venture to say that almost every film that Karlin produced after For Memory emerged from the complex and sometimes contradictory research that he attempted to squeeze into this film-essay. For example, at the time of his death in 1999, Karlin was working on a film called Milton (The Man Who Read Paradise Lost Once too Often) (1999). In one of the draft texts of For Memory, Karlin writes about Milton as the poet of the forgotten English revolution – the film would be ‘a vision and criticism of the appropriation and concealment of Milton in our culture’. Like Paradise Lost, Karlin’s own film would be a journey that would explore space, rather than time.v Indeed, the notion of popular memory occupies Karlin from this point onwards, notably in his extraordinary series of films for Channel 4 on the Nicaraguan revolution and its aftermaths.vi

Furthermore, this was the first film that utilised the rostrum-style dolly filming technique perfected by Jonathan Collinson (now Jonathan Bloom) – a cinematographer whose stamp can be seen on a whole swathe of British independent film, from Riddles of the Sphinx to Song of the Shirt and even Handsworth Songs.vii The technique essentially involves a camera weaving through, and often pausing on objects or photographs, an artificially lit studio filled with large vignettes. In For Memory, Collinson/Bloom’s camera drifts past architect’s models of a ‘future city’ – in fact, the architect’s models for Richard Roger’s post-modern edifice for Lloyd’s of London, which Karlin had managed to borrow for the shoot.

The rostrum technique is, perhaps, an exercise in remediation and distanciation. Certainly, the sci-fi connotations of the ‘city of the future’ recall this, albeit in literary or allegorical form, in which a ‘traveller’ messages us from the future. Yet there is also something about the manner in which these dioramas are presented that suggests a museum display. As a ‘museal’ optics, these vignettes recall Adorno’s essay ‘Valéry-Proust Museum’, a text cited by Karlin in one of his research papers for the film, in which the German theorist examines Valéry and Proust’s very different attitudes towards the museum.viii According to Adorno, Valéry was an elitist for whom the museum was a ‘mausoleum’ that ‘testify to the neutralisation of culture’, while for Proust, the museum was a place in which to discover and immerse oneself in experience. Surprisingly, Adorno – that supposedly hoary old elitist – sides repeatedly with the impish Proust against the puritanical Valéry.

These rostrum scenes reveal a deep ambivalence in Karlin’s thinking. He is understandably disturbed – outraged – by NBC’s Holocaust. Yet, he senses that this is an attitude that is somewhat elitist. In For Memory, Karlin (as narrator) speaks these lines:

For some, ill-prepared to deal with the transformation of a sacred memory into a fictional melodrama, the images of Holocaust were a desecration… but for others, these new reminders were the best that could be done to save these memories from the threat of oblivion…

How else might we remember, except through icons and monuments?ix In a time of amnesia, is melodrama a form that we might reluctantly accept as the vessel for memories that might otherwise slip from us? For Memory is both an examination of the problem and an attempt to find a solution, through the patchwork of essayistic rumination, talking head interviews and appropriated footage. It would be a project that would occupy Karlin for the rest of his life.

Colin Perry is an art writer and editor. He has written for a number of publications including Art Monthly and Frieze, and is the Reviews Editor of the Moving Image Review & Art Journal.

iThe reference here is to Raymond William’s famous analysis of televisual flow. See: Williams, R. (2003) Television: Technology and Cultural Form. 3rd edition. Routledge. Karlin had also written the following notes: ‘History as the contradiction of television’s flow. And yet retained within it. How does TV contradict the purpose of the historian.’

iiFor more on For Memory, see: http://spiritofmarckarlin.com/2012/05/08/picture-this-presents-marc-karlin-for-memory-1982-qa/

iii‘Puzzled by a project which refused to conform to the expected etiquette of programmes, the BBC consigned its screening to an anonymous afternoon slot.’ John Wyver, Thursday 28 January 1999. Available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/obituary-marc-karlin-1076691.html The programme was finally transmitted on 31 March 1986.

ivThe clip was used by Luke Fowler in his film The Poor Stockinger, the Luddite Cropper and the Deluded Followers of Joanna Southcott (2012)

vThere were also a number of promising suggestions that were not followed up on: interviews with Stephen Spender, and the historians Eric Hobsbawn and Christopher Hill.

viThese are: Scenes For A Revolution (1991), Nicaragua: Changes (1985), Nicaragua: Nicaragua In Their Time (1985), Nicaragua: The Making Of A Nation (1985), Nicaragua: Voyages (1985).

viiCollinson/Bloom was employed on numerous avant-garde or independent films. He did not work directly on Handsworth Songs, but his camerawork is said to have inspired it (interview with Jonathan Bloom, 8 October 2013).

viiiKarlin himself references this text in his notes for For Memory. See ‘Valéry Proust Museum’ in Adorno, T. W. (1986) Prisms. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT. pp. 173–186.

ixIndeed, Karlin wanted his films to operate like ‘monuments or tombstones’. See: Karlin, M. et al. (1980) Problems of Independent Cinema. Screen. [Online] 21 (4). p. 26.