Jenny Chamarette: Thank you so much for meeting with me, Evan. I was so pleased to be at the launch of the DWOSKINO commissions at the London Short Film Festival in January, and to get to the premiere of UNDERCURRENT 528. And thank you for being there as well, to share your thoughts on the process and the film’s relationships and Dwoskin’s work – it was great to have your presence in person. It’s a real pleasure to be interviewing you. I’ve just been absorbing your work, watching some of the LUX’s catalogue and listening to your voice and sound. As I was watching UNDERCURRENT 528, I noticed the resonance of your voice, and it felt like a caller, or a summoner into the space of the rest of the film. Could you tell me a bit more about how that relates to your practice as an energy worker and of course, an artist and how it links to the timbre and resonance of your voice in the film and your work more generally?

Evan Ifekoya: There are a lot of different questions in that and different layers to unpack, but what I will say is that, as an artist, as an energy practitioner, as a facilitator, I see myself as somebody who holds space for different kinds of things. Often, I think about it as a kind of world building, holding space for a way of imagining another kind of possibility, another way for being and existing in the world. And that manifests through my film work. You’ll have seen how I’ve moved through different kinds of practices, but it’s often about either inserting myself into the frame, and a particular kind of role, re-imagining who I could be, or who people like me could be. And then, as I started to disappear from the frame, it was again about recontextualising and reconfiguring certain kinds of archives and histories and thinking about what would it mean to speculate and reimagine them from the present. In relation to installations I create, it’s very much about transforming an environment and again opening up the possibility for another way of inhabiting space and time.

And I would say that’s all from a desire to bring a new way of being and existing into existence. My voice has become a real vehicle for anchoring that in, because, as I mentioned, I’ve tried to find ways to become, or to continue to be a presence in the work, but be more of a disembodied presence. So it’d be less about my physicality and about something more energetic or on the level of the aura. I think that’s also perhaps where what you mentioned about the timbre and the resonance of the voices, that contributes to creating a different kind of space and time. So rather than the voice feeling like it’s coming from the present, it might feel like it’s coming from somewhere out of space and time or out of space entirely. Or maybe at the same time, it might feel like it’s more of an interior voice, that’s reverberating and echoing through the chambers of one’s mind. It’s about holding a space for me, and the sound and the voice as a way of creating a container for that space that I’m trying to hold. The narrative voice at the beginning is very much about opening up that portal, and guiding that portal into existence.

JC: What it’s connecting to for me is the heritage of Black speculative fiction writing and poetry that connects to Sylvia Wynter and Octavia Butler. That kind of heritage of space creating and space holding, and thinking and being otherwise.

EI: They’re both big influences on my work – Sylvia Wynter is mentioned directly in the film – but Octavia Butler as well. I had the privilege in 2018 of getting to spend time at her [Butler’s] archives in Los Angeles, and that was a transformative moment for me. It was just before RITUAL WITHOUT BELIEF, the solo show I did in 2018. That was very formative, getting to spend time with [Butler’s archive], because I’d already been reading her novels, her works of fiction, but to then also be able to read her journals, her diaries… The way that she wrote to herself, the way that she was about speaking certain things into existence through writing, through the word, is something that continues to be an impact on the way that I work, and the way that I practice, and the role that voice and voicing plays in my work.

JC: Yeah, voicing is bringing into being. That makes a lot of sense. How incredible to have worked with and in her archives!

EI: Oh, yeah. I do feel very lucky.

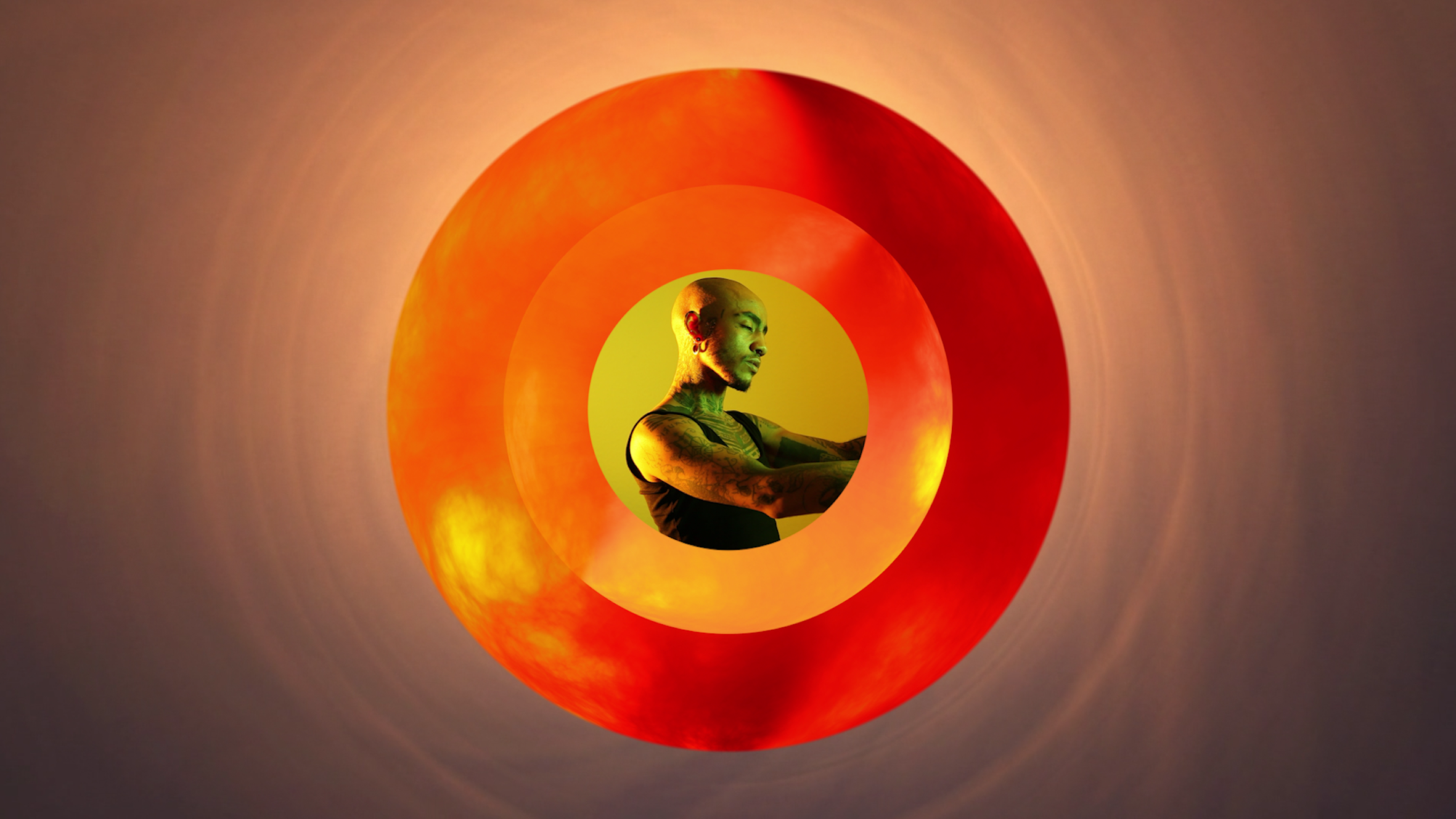

Undercurrent 528, Evan Ifekoya, 2022

JC: Oh, wow. I’m going to link to our next question in a very ungraceful way, and shift the context slightly, from voice to sound, and soundscape. And I know that after the LSFF screening you mentioned sound and soundscapes that the composers Gavin Bryars and Ron Giessen, designed for Steven Dwoskin’s films in the 60s and 70s. And we’ve mentioned Sylvia Wynter, but I’m going to drop her back into this question, too. In the opening to the film, you mention her as you said before, as a key thinker of the space and spirituality of drumming and sound. And you also worked with the drummer to develop those improvisatory rhythms in UNDERCURRENT 528. We started with a question of many layers and there’s also many layered thinking of sound to this one, too. I was wondering if you could speak a little more to that.

EI: Again, I’ve been very fortunate in that I was able to access a text of Sylvia Wynter’s called Black Metamorphosis, which she never published, but is definitely a Zeitgeist text, in that a lot of artists, filmmakers, musicians have referenced that text in one way or another. I was really lucky, through a reading group I was part of at a university I was teaching at, to get my hands on the full manuscript, and it really is a beautiful and dense and very rich text. In the first section, the first 100 or so pages in the manuscript (because it’s about 800 or so pages long!) she’s talking about the role of Carnival and ritual in the lives of Black diasporic subjects. She’s talking about dance and music as a way of connecting to one’s ancestral heritage, and one’s lineage.

Of course, that resonates for me, where sound and dance has been such a big part of my life and practice in so many ways. I also run a sound system [the Turner Prize-shortlisted collective Black Obsidian Sound System who also made a public statement outlining the inconsistencies of the Prize and its awarding bodies, particularly towards BPOC and queer artists and cultural workers] – that’s another project that I do. The way that she [Wynter] talks about the radical potential of dance, of the drum as well, was something that resonated for me. And I pick up in the film, I quote where she’s talking about the drum as an enabling mechanism of consciousness reversal: a way of transforming or reconfiguring one’s mental landscape, but also on an energetic level beyond the physical. She doesn’t necessarily use words like healing, but it has a kind of transformative potential.

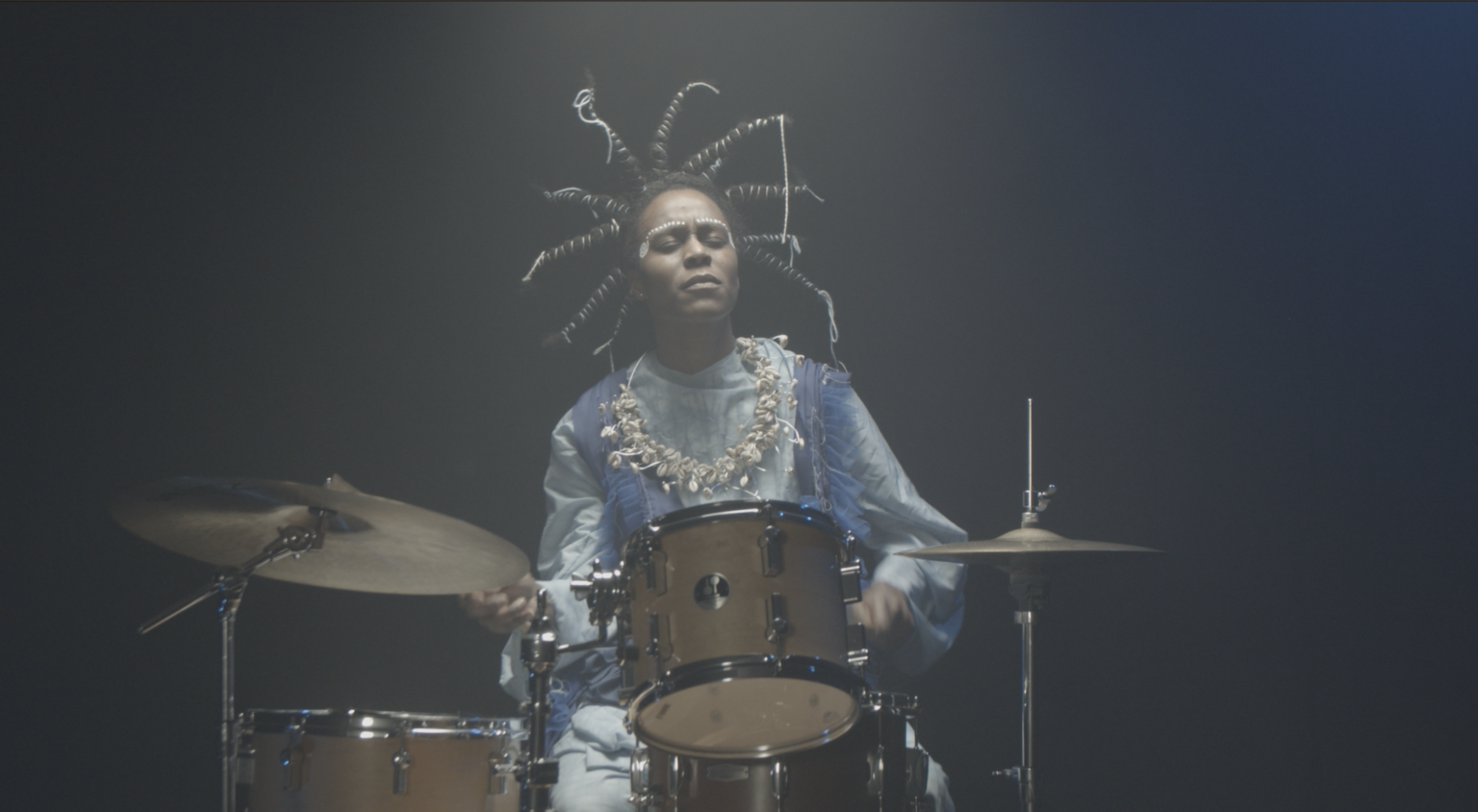

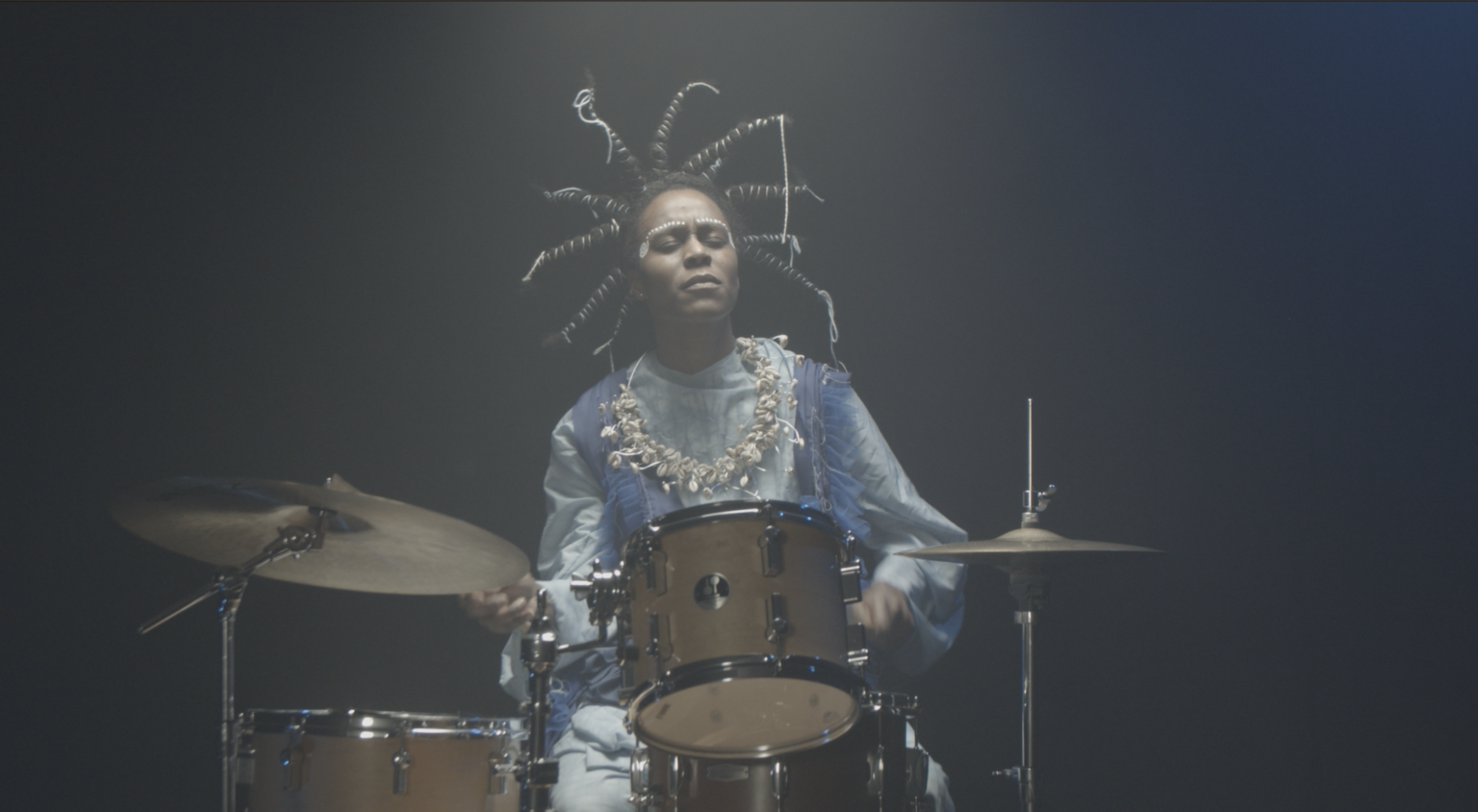

With the film, which is also part of a larger body of research I’m looking into about the role of the drum, I wanted the drummer and the role of the drummer to be a very significant one within the film. It was great to connect with Remi [Graves], the drummer, and I shared with them some of this research and thinking. You’re right – we were in the studio, we had a drum kit, and they started playing, and what I was really interested in was observing and witnessing the journey that Remi went on in their own exploration with the drum, and the connection that they have with that instrument. It was that I was wanting to pursue and journey with. There are some beautiful moments in the work where you see them reach a crescendo, where you see them reach moments of tiredness, which can only come from really giving it your all. I was interested in going with that, and journeying with that. And then, from there, that becoming the building blocks for the score, which I worked on with a techno producer called Tygapaw.

JC: I think you’ve collaborated with Tygapaw previously in some of your work?

EI: I actually haven’t. Tygapaw has done some stuff with B.O.S.S, with the sound system I’m part of. But I often do work with musicians and sound people in my work. This is the first time they’ve done a score for me.

JC: My mistake! It sounds like you’ve drawn in new collaborative partners, as well as established ones in the process of making this work, as part of that wider work.

EI: Yeah, that was important to me. because the film was made during the moment we’re in, in the middle of a global pandemic. And actually, the connection came from a place of getting a lot of nourishment from listening to Tygapaw’s mixes. They make a lot of DJ mixes that they post on their SoundCloud and it was at a point where clubs weren’t open. I was doing a lot of my raving at home, and they were just somebody I was tuning into a lot and getting a lot of joy from. So I did just – and, you know, Dion [McKenzie] Tygapaw is based in New York, we’ve never actually met IRL – but of course, we have mutual connections, because we are within a network of creatives within the Western context. So it was easy enough for me to reach out to them, but it was very much from a place of just being like, hey, you know, what you do brings me a lot of joy, can some of that joy become part of this work?

Undercurrent 528, Evan Ifekoya, 2022

JC: A place of making space for joy. So necessary, and so much a part of the heritage of work of Black musicians, poets, writers, speculative fiction writers, as we’ve already mentioned. And the way that you’ve just explained the witnessing of Remi’s journey through their connection with the drum and the instrument and the drumming, and their body in relation to that practice, has helped to connect something in my mind to the relationship between you as the artist, filmmaker, space holder, and Remi as the drummer and the breath-work workshop that we also see in UNDERCURRENT 528. I feel like you’ve just built that bridge for me in a different way: that part of the connection is not just the relationship of sound in one space to sound in another but the journeying of both. Thank you for that. That’s just deepened my sense of enquiry.

At the start of UNDERCURRENT 528 you explain in voiceover how the network of connections in the film are set up. And we’ve just been talking a little about what is both a very present and material network and a speculative and future oriented network, as well as deeply connected to the past, to ancestors, to individuals in your life, and more. You explain in the voiceover at the start of the film, how the connections are set up, making space for breath-work workshops for queer, trans and non-binary people of colour, that form part of your wider collaborative network. And those sections in the film that capture the workshop speak to me about what I would describe as the intuitive and internal erotics and the healing sensuality of breath. However, the space of the camera feels both participatory, but also careful about who and how the participants are held in the frame. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about framing, and participation?

EI: There’s an ongoing concern for me around the slipperiness of documentation and liveness. With the work, there are these different layers, because the workshop is unfolding – the workshop was happening in real time. It was constructed, in that a friend of mine is a tantric breath-work facilitator. With them I created a workshop, and then we invited people into my community to participate. Some of them took part in person. And the workshop takes place in my home – I live in a live-work space. So yes, it was also an unfolding in my home, which also felt like a connection to Dwoskin, who did film a lot of his works within or around his home environment. There’s the fact that [the workshop is] being filmed as it’s happening, but then you also have the participants who are taking part over Zoom. So we had that, the double screen, but the workshops happening simultaneously. I went into it thinking, okay, we’re exploring Tantra, which is very much about exploring sensuality, through the breath, through the body. But then I wanted to think, okay, these are subjects, these are people who are used to a gaze, which previously or at other times might be exploitative. And I was coming into it very mindful of that, to not want to in any way hinder or impact their experience. They did go into it knowing it would be filmed, but I also did say that I would be very mindful about how and what was filmed.

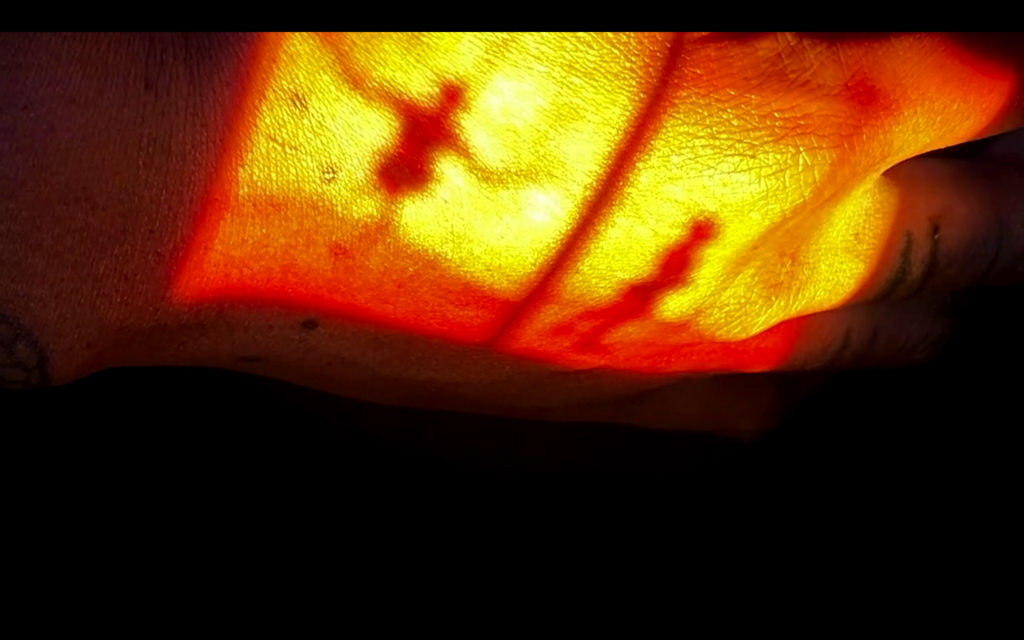

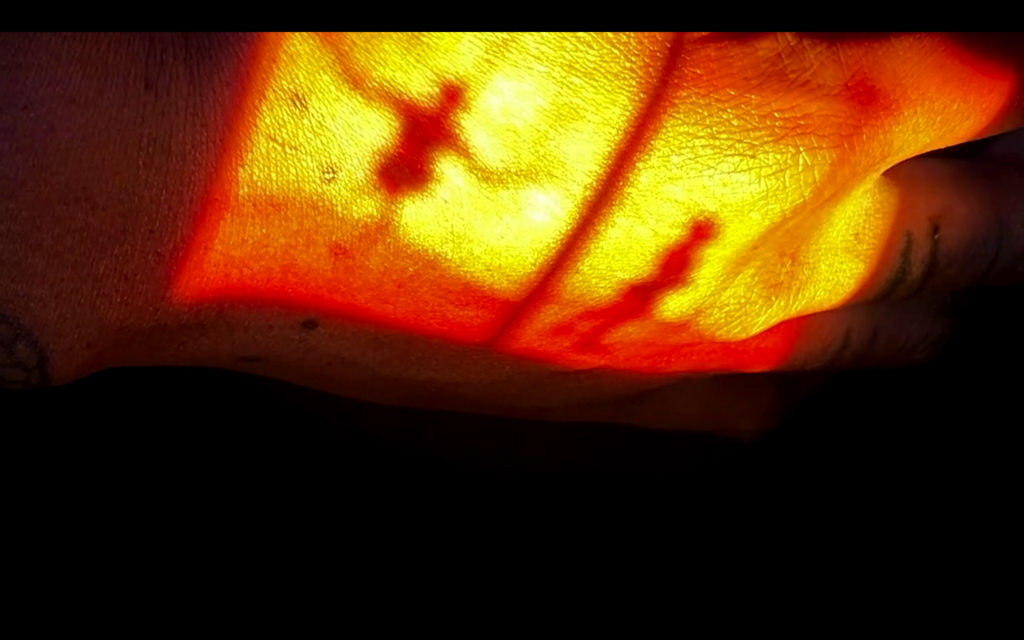

It was great as well to work with Rufai Ajala who was the director of photography, who is also an intimacy coordinator for film and production. They also brought that knowledge and understanding. And there are these moments in the film, and techniques where the lens flares and the image becomes obscured, and this was all happening live and in the moment – those weren’t post production effects. That was because we came into it thinking, okay, how do we ensure that the people who are involved don’t feel compromised, or that they’re on display for salacious reasons or for the pleasure of somebody or something outside of themselves. I didn’t want to do anything that could jeopardise the pleasure that they felt they could bring into the room and have in that moment in time. And I guess that was about how we framed the invitation to the people who participated, and the knowledge that Ru brought to being the camera person, being the person who was the eye of the camera for that sequence.

Undercurrent 528, Evan Ifekoya, 2022

JC: The way that you’re speaking about care and sensitivity and attunement to the participants, and what remains visible, and what is not disclosed within quite an intimate space: that’s really fascinating to me. It chimes with some of the thoughts I’ve had about Dwoskin’s later films, his very late films, especially where his mobility was extremely constricted, so the spaces where he could film were very limited, but also that he was still wanting to explore questions of desire. He was foregrounding himself later in his career, I think, partly because of wanting visibility for a disabled body, for his disabled body. He wanted that to be part of the frame. So it feels like your and his practices are related inquiries. They’re not the same. But they are kind of enmeshed in an ethics of care. That would be the way that I’d think about it. And speaking about Dwoskin helps me to circle back to the last question, which is about the films that most spoke to you as you were developing the commission. Now I know you mentioned [at the LSFF screening] BALLET BLACK (1986), Dwoskin’s documentary about the Ballet Nègres, the first Black dance company in Europe, founded by Jamaican dancers, Berto Pasuka and Richie Riley as being a cornerstone for the ways you responded to Dwoskin’s work. And I was wondering if you could tell me a bit more about that, about the influence, either of content or form or inspiration, or maybe something about archival thinking, about that relationship between BALLET BLACK and UNDERCURRENT 528?

EI: There were definitely a few of his works that influenced the work, but I would say on multiple levels, BALLET BLACK did. It became a way for me of really structuring the treatment of the film. I guess something that’s not always visible in my work is that I often do have to create a structure or a framework to work from because of how much is either more improvised or poetic. With BALLET BLACK I was really struck by these three specific roles or protagonists within the film. There’s the reoccurring image of the drummer, the reoccurring images of dancers, and the interweaving of them workshopping and rehearsing. So again, there’s the live moment that’s unfolding, and then there’s the performative moments and more studio-based moments that are weaving in and out. They then became my anchors within the film: the Dancer, the Drummer and the Workshop, which are very much the key elements in the film. And the fact that there’s a narrative voice [in BALLET BLACK] and I did start with a narrator, and there are these moments of working with what seems like archival footage, which, again, is another way of me to insert myself into the frame. And so very much on a visual aesthetic level, and also the way that the dancers were filmed, the way that certain kinds of body parts were highlighted [in BALLET BLACK] I definitely thought about those things in relation to the dancer [in UNDERCURRENT 528]. I definitely got a sense watching the film about certain features that Dwoskin found desirable, that Dwoskin took pleasure in seeing, and there’s something in that, that I wanted to echo in relation to the shots with the dancer.

JC: There was a screening of Dwoskin’s early film TIMES FOR (1971) at the BFI on Tuesday [1 February 2022]. And that film is very much focused on what you might think of now as quite standard frameworks of visual pleasure, and visual unpleasure, and unpleasuring what might be conceived to be visual pleasure in 1970. And it sounds to me that some of the aspects of visual pleasure that you’re exploring are a completely different sort of pleasure and pleasuring and joy, that is emerging from your focus on body parts and movements. On pleasure as connectedness perhaps rather than as disconnectedness, pleasure as intimacy.

EI: Definitely. Yeah, it’s definitely a way of getting closer, but also about an invitation to get closer to me and my, and the lens through which I look as well. Definitely an invitation.

JC: Yeah, it feels like it’s a double invitation: an invitation between you and the dancer, an invitation between the viewer, and you, and the dancer.

EI: Exactly

JC: Which feels like a beautifully queer model of the filmic gaze. I love it. And it’s been really enlightening for me to hear more about your process. At the moment in my mind, I’m rewatching UNDERCURRENT 528, re-seeing it through different frames. Also, with an invitation to take more pleasure, which is such a delightful invitation.

EI: Yes, exactly, always!

JC: Especially in our current times. Thank you so much. This has been such a pleasure.