The appearance of moving image is guaranteed by the fidelity of the screen, that “medium of variation” defined by a collection of contingencies; the mode and ratio of projection, the saturation of light and colour, the distance between the lens of the projector and illuminated projection surface.

Gilles Deleuze enigmatically claims that “the cinema does not just present images, it surrounds them with a world”. Given the influence of Henri Bergson on his analysis of cinema, as set out in Cinema 1and Cinema 2, this implied ‘world’ invariably alludes to the specific temporalities of film, the duration of the flickering celluloid frame, the subjectivising affects of projection speed, and the illusion of image-movement across the surface of the screen. But where “anything can be used as a screen, the body of a protagonist or even the bodies of the spectators”, and therefore “anything can replace the film stock, in a virtual film, which now only goes on in the head, behind the pupils”, Deleuze’s general understanding of cinema can also be considered to transcend the mere presentation of images to also describe and incorporate the ephemeral framework of cinema, as guided by the conditioning principles of the screen.

Falling under the remit of ‘expanded cinema’, but exceeding fundamental concerns with the materiality of film, the French ‘projectionist’ Pierre Leguillon notably stages performative slide lectures and film screenings that explore the reproducibility of the image, in both moving and static forms, via the ‘variable medium’ of the screen. Dedicating his mobile moving-image project La Promesse de l’Écran(The Promise of the Screen) to the task of highlighting the “peripheral aspects of cinema”, Leguillon’s experimental manipulation of screening formats emphasises not only how the ‘world’ around the presentation of moving-image can be drawn out through myriad configurations of the screen, but also how this staging in turn can produce unique sites of aesthetic encounter, where “sharing an image together can be a moment that you cannot reproduce”.

Romantic in title and itinerant in nature, La Promesse de l’Écran functions as a cinematic troubadour. Starting out in Paris before travelling for a season through Bordeaux, and stopping off in individual venues across Europe, this diverse programme of projection, installation and performance stimulates a critical reappraisal of overlooked cinematic phenomena. Taking the regular, reliable format of a monthly film club, initiated by Leguillon in November 2007, and historically coinciding with the election of Sarkozy as French president, La Promesse de l’Écran evokes the spirit of a renegade speakeasy; comprising an anachronistic hybrid projection room composed of a 4:3 ratio screen invariably installed in each venue in front of a small wine bar. Screenings are privileged before serving time, with Leguillon presiding over a curated programme of artists’ film and video before the removal of the screen and opening of the bar: perhaps a strategic ruse to retain a captive audience? – As Leguillon himself says, “the more you stay, the more you can see”.

Site-specificity is an integral aspect of Leguillon’s conception of La Promesse…, as he explains: “I work on what surrounds the work, the artwork, the museums, the situation, I always prefer to be on the margin than the centre”; a statement which is paradigmatic of his penchant for ‘marginality’ through the curation of reflexive screening programmes. One iteration dedicated to painter Josef Albers exemplified the geometry of the screen through a combination of moving-image and found objects, in which Leguillon projected Albers’ famous Homage to the Square series, a triumphant demonstration of the power of colour alone, alongside a display of LP covers designed by Albers during the 1960s and John Baldessari’s Six Colourful Inside Jobs (1971). Footage of Baldessari imitating a household handyman redecorating interior spaces in primary colours offered a performative continuation of Albers’ canvases, accentuating the actual/virtual dimensions of the screen, while also reflecting the unusual domestic context of the screening.

Following versions of La Promesse… went further to invoke the screen as a permeable structure through delivering, as Deleuze describes, the formation of an image with “two sides, actual and virtual”, as seen in Cecil Bas’ sculptural interventions installed across the projection space. Here translucent canvases, which imitate the glossy texture of painted squares applied to adjacent walls, hang from the ceiling, simultaneously reflecting the interior features of the space, whilst the visual imagery of projected video works play across their surfaces.

Leguillon’s preoccupation with cinema ‘credits’, the preface and appendix of film, was also explored in his slide carousel lectures, and was additionally addressed in his Saul Bass/Sacha Guitry: Title Sequences screening programme. Here two short films consisting solely of motion picture title sequences by Bass and Guitry respectively were elevated from marginal preface pieces to main cinematic features; Bass’ signature graphic credits, iconic short-form animations in their own right, dynamically contrasted with the comic introductory sequence by Guitry, in which twenty different actors are seen performing the role of one character, but none of whom continue to feature in the proceeding film. Implementing a specific curatorial agenda, La Promesse de l’Écran pushes latent cinematic conventions firmly into the centre of the screen.

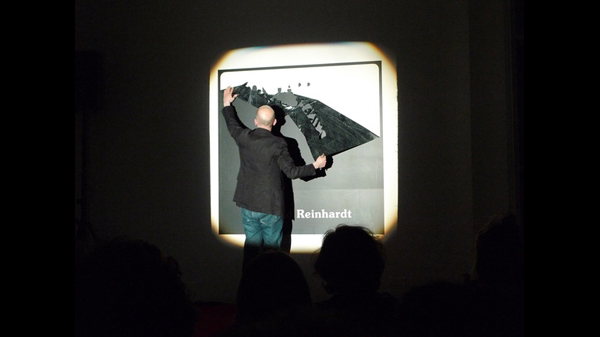

Significantly, Leguillon’s preference for a 4:3 ratio projection screen, a format typically used for data presentation, connects La Promesse…with his small-scale photographic slide presentations for which found celluloid images are reconfigured into specific carousel sequences, to interrogate, through the composition and presentation of the image, the subjective fabrication and dissemination of historical narratives via authoritative formats, most recently staged for a UK audience in Non-Happening after Ad Reinhardt by Pierre Leguillon, with Seth Siegelaub at Raven Row, London in 2011. The autonomous pop-up staging of La Promesse de l’Ecranalso echoes the portability of Leguillon’s slide show screening models, both flexible in their production as “like a sentence you can change the words very easily”, allowing for adding or removing slides at the very last minute before a lecture or performance.

The intention for Leguillon is never to look for or recuperate a ‘lost’ original, but rather express the gap between generations of imagery across both static and moving-image formats. Considering its emphasis on modes of representation, discourses surrounding the ‘reproduced’ image undoubtedly emerge as a key point for discussion here, and inevitably invite associations with the politics of representation, as set out in Walter Benjamin’s Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In it Benjamin states, mechanical reproduction of a work of art, such as the Leguillon’s light-based projections “represent something new”, certainly in terms of the manufacture and distribution of the image, but also in the wider arena of his artistic practice, wherein the artist also attempts to think beyond celluloid to print by finding a “way to project without a projector” in his ‘silent screenings’. Here the Leguillon rejects illusory projection in favour of material presentation of the image, successively unfolding large printed posters under a spotlight in performance.

Nevertheless, even for Benjamin, “the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be”. Above this remains Leguillon’s performative objective, working the grain of technology and in the face of obsolescence threatening celluloid film and photography to make the image present through the unique dialectic of the screen and original temporality of the event. As such, the phenomenon of the ‘screen’ in La Promesse de l’Écranpromises the potential to transcend its material structure, it is the primer for psychic projection, the “brain of the screen”, a virtual veil onto which illusions of presence and consciousness are inscribed.

Amy Budd is LUX writer in residence for October 2012, she is a writer and researcher based in Norwich. Since graduating from Goldsmiths with an MA in Contemporary Art Theory in 2009 she has been a regular contributor to the online magazine This Is Tomorrow, and has featured writing in the periodicals n.paradoxa and Kaleidoscope. She is currently working as a Research Assistant for Norwich University College of the Arts, and is the steering committee chair of OUTPOST Gallery, Norwich.