The following interview took place on the 20th of October 2010, at Jean-Marie Straub’s home in Paris, three months before the start of what is currently designated as the “Egyptian Revolution”. While the outcome of this uprising is not yet known, the film Trop Tôt, Trop Tard as well as this conversation have now gained quite a different dimension, and seem, above all, timely. This interview is being published to coincide with a screening of Trop Tôt, Trop Tard, at Tate Modern on 12 February 2011, on the 19th day of the Egyptian uprising. Unable to go to Egypt to exhibit the ongoing work Il n’y a plus rien that research around Trop Tôt, Trop Tard was part of, the event was organised with some urgency, as a way of foreseeing the present.

Céline Condorelli: I only have three questions for you.

Jean-Marie Straub: That’s very good, because I don’t have anything to say about this film.

Celine Condorelli: I am really wondering how to address a country like Egypt, and speak of a city like Alexandria, or of the situation following the Egyptian revolution. What is the appropriate position? The film Trop Tôt, Trop Tard is very clear in these terms, explicitly locating where it looks and speaks from, or reads from. My three questions are all about this, about positioning. So Trop Tôt, Trop Tard was made in 1981, and I know you had been filming in Sicily, just beforehand. How did you get to Egypt, why choose sites of Egyptian rebellion in the second part of the film, following the French revolution. Why Egypt, why the Egyptian revolutions?

Jean-Marie Straub: It was purely by chance, just like everything that happens in this domain. It is a chance encounter. We went to Egypt the first time in 1973 or ‘72, I do not remember, for Moise and Aaron. Because while Moise and Aaron is an old project, of 1958, we wanted to shoot it, not in Egypt, but halfway somewhere, possibly in Italy, without knowing where exactly. In the end we shot a part in an amphitheatre in Massa d’Albe in the Abruzzi, and the last part a little more south. We went to Egypt in order to understand life there, and to bring back some objects, not many, a jug… a camel saddle, stupidly… Coming back to Rome afterwards of course we had a lot of unanswered questions, what is happening in this country, how did it get to this, after the coming of Napoleon and before… One day we were just hanging out in a bookshop not far from us on the other side of the bridge, and there we found a book, in which we found informations, which is the one from these two gentlemen.

CC: Mahmoud Hussein.

JMS: And that’s when we had that idea. And of course the film does not have anything to do with what they wrote, with everything they say, and all the facts they mention; because they had not seen what they talked about. While writers say things and give information, they are not interested in geography, in topography, in places etc… and we went to check those informations’ topography, the geography of the thing. That is all. The same thing happened to us with Fortini / Cani. There is a sentence in Fortini / Cani in which he says: “I consigli comunali delle Apuane rifiutano il ricorso in grazia, dopo il comune di Marzabotto” [The municipal councils of the Apuane (where twenty three years ago Reder and his helpers killed hundreds of people) oppose the petition for reprieve, after the municipality of Marzabotto]. That was all. The writers do know the facts as they put them down on paper, but they hadn’t seen most of the places… when they saw the first screening of the film at the French cinematheque here in Paris, one of them was crying, for his country, when he saw his country. We just went and filmed things they did not know. We went a first time to see all these places from north to south, from Alexandria to Assouan, and then we went back to shoot, a year or six months later, I can’t remember. That is all.

CC: Why did you decide to place this in relationship with the French revolution? Was it first Egypt and then France, or the opposite… which way did the film come about?

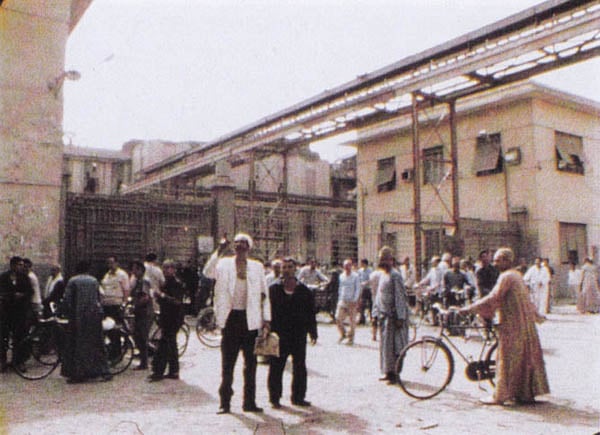

JMS: It consists in doing a diptych, that is all. To compare places that in France look deserted with places that in Egypt are full of life and people. It is only a contrast. What there is in this from an ideological point of view, I don’t know. But of course 1789, that Danièle speaks about in the beginning [of the film] is beforehand. You need to limit yourself in life, especially in matters of aesthetics; you cannot do everything at the same time. Nasser’s revolution caused the authors to leave Egypt, but they first had to spend I don’t know how much time in one of Mr. Nasser’s concentration camps, before leaving for France. I think they spent two years in there. There. But you do see at the end of the film a news edit, and you see Nasser himself speaking and saying: “Good people, blow off your lights, it is cold, it is snowing, and go home quietly, stay there, we are going to take care of you”. You see him in the film and even Neguib, sitting on a hospital bed shortly before he died, and taking the phone from his bedside table… you do see them. And you also see several glimpses of what you call Nasser’s revolution. The end of the film is Nasser, even though we do not make anything glorious out of it.

CC: This was a question in relationship to positioning, as I already mentioned earlier. Knowing what position to speak from is a difficult thing in the Egyptian context.

JMS: This is exactly what fascinated us when we read this book, and the preface in particular. That’s where we found some information at last, on something that seemed nebulous to us on our return from Egypt, like a fog. We said to ourselves, it just isn’t possible, how could they … did they never rebel, and what happened?

CC: And you clearly chose to place yourselves in relationship to these revolts. Did you go to Alexandria in 1981, when you were filming? Had you already decided not to film there?

JMS: We’d been there a year earlier. We had already been in 1973; we went three times before going back a fourth to film all this mess. We went twice for another film, and then we went back, and then went back again to find the locations, the villages on which there were informations given by the two Egyptian writers, and at this point we went back six months or a year later to film. We didn’t decide, it was their (Mahmoud Hussein) text that did. They placed themselves later, after the Alexandria riots, because they wanted to speak about something that lead to Nasser.

CC: How was this translated to how you placed yourselves in the filming? There is a lot of consideration in the distance of each scene, between the camera moving or staying still, with the fact that people do not seem to be disturbed by its presence… How does one choose the appropriate position for the camera?

JMS: That is the least one can do when filming…. You need to go there and walk around. Walk around a place or a village three times, and find the right topographic, strategic point. In a way that one may be able to see something, but without destroying the mystery of what one sees… but this isn’t specific to this film, this is the case in all our films.

CC: Especially the topographic point, I really recognised this in the film Sicilia!

JMS: That is what cinema is. The writer gives informations that he puts down on paper, that come out of archives. The same thing happened to Engels, who started from Kautsky’s text, and said to him “you didn’t understand anything”, and enumerates all these facts. All the facts he refers to become the list of grievances of the French revolution. So we went to the archives here in Paris, and we got the lists. We had two big piles, carefully tied with ribbons, that barely anyone had ever opened… We unwrapped them cautiously, and checked the facts. And then went from the North of France to the South, to see where all this happened, where it had taken place. What was left of it. And what is left of it? Nothing, there is nothing left. The topography, nothing else.

CC: But does the topography speak, can it have a voice?

JMS: Well cinema is, or should be, the art of space. Even though a film exists only if that space is able to become time. But the basic work is space. As Mallarme said: “Nothing will take place, but the place.”

CC: The film is also very clear in the relationship between text and image. Mahmoud Hussein’s text seems to be the context, the large context, that names sites but doesn’t necessarily have an immediate relationship with them, it remains at an abstract level of politics. But the images, the landscape itself appears as a character in the film – more than the text itself, although the latter is present as a voice. This relationship with the voice over… you specifically asked the writers to read it themselves?

JMS: Yes, one of the two reads the text; he reads it in French and as he speaks very good English, also reads it in English. Danièle reads the other text. What you saw was a French version?

CC: Yes, it was.

JMS: They (Mahmoud Hussein) always refused to have the film shown in Egypt.

CC: Do you know why? It was not possible to find their book in Egypt, no one I spoke to had even heard of it.

JMS: Because they didn’t want it to be, that is all. And they are not known in Egypt because they left, they went on exile, and Egyptians do not want to know them, that’s all. They were incarcerated in a camp there for two years after all.

CC: Yes but there is nevertheless a strong history of opposition in Egypt. There are nevertheless people who followed the history of Marxism Maoism for example.

JMS: Official ideology in Egypt is very respecting, and we are talking about two characters that are not respectable.

CC: Yes but still, they have been deleted a bit, deleted from Egyptian history. Could you explain me the relationship between text and images? Between what one sees and what one hears?

JMS: I cannot explain that to you. That’s the film. That’s the least one can do when making a film. People do not do this anymore, or hardly, and this is a decadence, that’s all.

CC: You mean that people do not work on this relation anymore? This creates a specific distance, because the images are immediate, one is very close.

JMS: I do not like the word distance much, because everyone thinks the word distance comes from Brecht. Distanciation (in French), Brecht never spoke of distanciation. He spoke of Verfremdung, which means strange, it is completely different. The French always translated that with distanciation, and the English are even worse, they translate it with alienation.

CC: How would you translate it? Making uncanny?

JMS: The operation that consists in making things strange.

CC: Estrangement then.

JMS: But this film is really about this, the French part as well as the Egyptian part, by it not being fictional, and yet the fiction becoming reality. There is an element of fiction, but it comes from the place itself. When you see a donkey passing by chance, and of course this only happened for one take, pulled with a rope by a man, with a woman sitting on it… of course this becomes mythological.

Things like this cannot be anticipated, and are the gift of chance. But of course you need to have enough time, margins, and space for things like that to occur. Which is to say you need to behave as a filmmaker and not a paratrooper. Filmmakers nowadays are paratroopers; they fall from the sky, and show something that they did not have time to see, film before seeing anything, and never look at anything before seeing, or look again at something after having seen it, so… If one was pretentious, one could call that… well, it is a bit like counter point. This one (pointing at the cat on the table) is called Neguib.

CC: (Looking at the cat) We were just talking about you! Is this the relationship in the film, knowing how to look, knowing how to wait to be able to see what one sees, in terms of what is too early or too late?

JMS: I hope so. I am pleased to hear you say it, that’s all, but I cannot add anything to this. And as I do not have anything to add to this, the film is there and that is all, and I hope it exists.

CC: It exists, and does exist today, proof is…

JMS: … That you are here (he lights his cigar again).

CC: And I am here on my return from Egypt, where I took the film with me. Coming back, I decided to come and speak with you.

JMS: Griffith said: “What modern movie lacks is the wind, the moving wind through the trees. ”

CC: Would you consider having the film shown in Egypt?

JMS: Yes, I would, but I do not travel anymore. I would like them to see it, that’s all. One must never take pity on intellectuals

Interview credits:

D.O.P. Sarah Beddington,

with thanks to Merel Cladder who first told me about the film.

Celine Condorelli works with art and architecture, combining a number of approaches from developing structures for ‘supporting’ to broader enquiries into forms of commonality and discursive sites. She is the author/editor of ‘Support Structures’ on Sternberg Press, 2009, and one of the founding directors of Eastside Projects, an artist-run exhibition space in Birmingham, UK. Current exhibitions include ‘Il n’y a plus rien’, first movement at Manifesta 8, Murcia (sept 2010- jan 2011), and Second Movement at A.C.A.F, Egypt (feb-march 2011).

www.celinecondorelli.eu

www.supportstructure.org

www.eastsideprojects.org

The artist Uriel Orlow, currently collaborating with Celine Condorelli, has also curated an online exhibition of three films by Egyptian artists related to the problem of the president