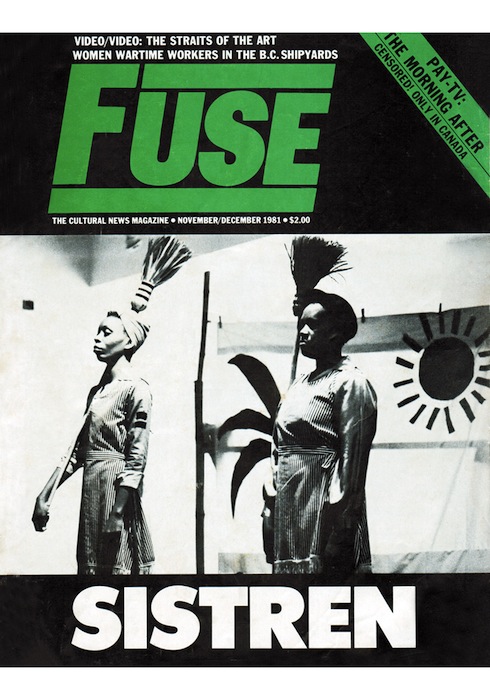

Sistren Theatre Collective, which means ‘sisterhood,’ was founded in 1977 in Kingston, Jamaica by working class women in the social, cultural and political context of Jamaica’s socialist experiment of the 1970s following the first decade of independence.

The founding members included Vivette Lewis, Cerene Stephenson, Lana Finikin, Afolashade (then Pauline Crawford), Beverley Hanson, Jasmine Smith, Lorna Burrell Haslam, Beverley Elliot, Jerline Todd, Lillian Foster, May Thompson, Rebecca Knowles and Barbara Gayle. Assisted by the actor and director Honor Ford-Smith, the Collective was forged through a government initiative to improve employment in Jamaica’s poorest communities. Plays like Downpression Get A Blow (1977), Bellywoman Bangarang (1978), Nana Yah (1980), QPH (1981) and Domestik (1982) along with community drama workshops, presaged the documentary Sweet Sugar Rage in 1985.

Sistren’s plays and workshops were a place to stage the histories and experiences of black Caribbean women at the intersection of patriarchal oppression, racism and social class, to promote education, employments rights, unionisation, reproductive rights and decolonisation. The Collective toured throughout the Caribbean, North America and the UK and parts of Europe. Sweet Sugar Rage sits alongside Miss Amy and Miss May (1990) and The Drums Keep Sounding (1995) as well as life histories, magazines and screen prints that further expanded the scope of their theatre, education and community activities.

Sweet Sugar Rage documents the themes and methods of Sistren’s workshops and theatre in the context of their wider efforts. This takes the testimony of women that worked in the sugar cane fields as the basis of drama workshops bringing rural and urban women into dialogue to address the exploitation of working class women’s labour and the patriarchal attitudes of employers and unions alike. Following the methods of Freire’s ‘conscientization’ and drawing on Caribbean storytelling and ceremonial traditions, we see the women collectively and performatively take charge of staging and re-staging ways to challenge the systems that oppress them and offers a methodology of learning together to effect social change.

In June 2020, Conal McStravick spoke to Sistren founders Honor Ford-Smith and Lana Finikin about the origins of the collective in Jamaica of the 1970s and 1980s. This reflected on the role of Sweet Sugar Rage in Sistren’s local and international activities at that time and what it means to look at this work in the present in light of Sistren’s historic activities and the shift from cultural work to community care in Sistren and in particular Lana’s ongoing work with GROOTS, Jamaica and other agencies to address women’s health, gender-based violence and the safety, health and welfare of communities and their survival during the ongoing state of emergency measures imposed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interview with Honor Ford-Smith, Toronto, Canada, June 2020

Conal: If I gathered correctly you studied drama before you started Sistren Collective?

Honor: Sistren were part of a whole social movement that existed in 1970s Jamaica, during a period of major social change. A lot of things happened in that time, including the opening of the Cultural Training Center in Kingston responding both to the need for training people in drama, but also for the need to address community based concerns through forms of education; that was how Sistren came about.

Sistren were one of a group of grassroots people who came to the school to ask for help to form their own organizations. There was a group of prisoners from the gun court, (a special court that deals with firearms convictions in the Jamaican justice system), there was a theatre started at Bellevue, the psychiatric hospital and there were the dub poets… All of them were connected to the school at that time.

Conal: I encountered Sweet Sugar Rage in 2008 through Cinenova, the feminist film and video distributor who sent preview copies of films and videos from the collection to Transmission Gallery, Glasgow where I worked as a committee member at that time.

Cinenova works were being screened at the invitation of the artist Kathryn Elkin, who curated an exhibition titled Moot Points on socially engaged practices and feminist historians, artists and activists were invited to screen works from the collection.

At about the same time I had learned about Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal’s pedagogical and theatrical methods, so I guess Sweet Sugar Rage struck a chord then and again recently as my thoughts were coming together of images of survival on screen.

There’s a great generosity in the work as a piece of documentary film making because the audience are invited into the theatrical methods of Sistren and a collective and embodied learning embedded in the work is shared. The learning shared in the workshops and the learning shared by the theatrical audience is shared with the video audience, and I guess that’s been something that’s really important to me in terms of my relationship with video and the potentials of video as a learning tool.

Several years ago I started a project responding to Stuart Marshall (who was screened in Parts 1 & 2) working from the context of his works and their production titled Learning In A Public Medium and I suppose some of the things I’ve learned from doing that project have entered into Picturing A Pandemic, namely thinking about images of survival on screen and thinking about ways that video or film technology and video has offered tools to people in terms of their various struggles.

I suppose I’m interested in what it means to look at this work at present in terms of what you were trying to achieve then and how those films, I think three in all, expanded the reach of Sistren.

Honor: There were several films and I think they increased our distribution more and our reach outside of Jamaica. The films were picked up and shown at a number of radical film festivals. So for example at the Cuban Film Festival and in Martinique, and so on.

The first was made by UWI students in the early days of Sistren Theatre Collective and I don’t know if that still exists. Then there were Sweet Sugar Rage (1985) and Miss Amy and Miss May (1990), which was a documentary produced by Sistren about the early Jamaican feminists Amy Bailey and May Farquharson, who were active in the struggle for political reform, and finally a third called The Drums Keep Sounding (1995) (on Louise Bennet-Coverley aka ‘Miss Lou’). I have no idea where you can get that or where it is right now because it wasn’t made by me and I don’t know who distributed it.

So for some reason Sweet Sugar Rage is having a bit of a renaissance. (I don’t know why because it was dormant for so long?) It was produced in 1984 while we were trying to expand our work beyond the stage. We had been doing these big productions, many of which toured all over the world, including to Britain. This was part of a moment that looked at what was happening not just among people making work for the stage, but also, to look at the work of working class women on the ground in Jamaica, at the same time that this was also the moment that neoliberalism was taking hold in Jamaica.

There had been a socialist experiment in the 1970s and that was totally undermined by the Americans, whose interference threw the country into conflict and chaos and then, the right wing came into power triumphantly in the 1980s. We were trying to struggle to survive in that context, by making theatre to keep the political vision of justice alive and to keep women’s voices before the public. So it was in that context that we were working with women in the sugarcane fields.

Our work tended to have three kinds of thrusts. The first was testimony, which you see very much in Sweet Sugar Rage. There’s a lot of testimony from the women about their conditions and from the basis of testimony, finding out from what they were experiencing. The second was ceremony, which you don’t see a lot of in Sweet Sugar Rage, but a lot of the other work draws on older rituals in order to structure the meaning or the way in which we tell the stories and summon people together. The third element is witness, people witnessing each other’s stories and then trying to make connections between their stories and the bigger picture of national and global needs.

Conal: In the 1981 Fuse magazine article you authored, you talk about the extent to which at the beginning there were practicalities that needed to be addressed namely how you would work as a collective to improve education and to address audiences. Obviously therefore Sistren had an enhanced role in terms of the education people could gain through participating (and the pedagogical role).

Honor: We are often linked with Boal, but the link was very tenuous… I mean we read his stuff and thought it was a good idea, but there’s a whole other long history. Certainly I would say that Freire was a major influence from the get-go, he was important.

Conal: …you mention Freire’s The Pedagogy of the Oppressed in this same article.

Honor: It was also the idea of critical consciousness or ‘conscientization’ that Freire had, which was the idea of using education as a way of help people to become more conscious of the world around them… It was a different moment as we didn’t have technology. We didn’t have a publishing house in the region and as the publishing houses were outside of the region it was expensive.

Conal: That makes a lot of sense in terms of the various attempts to use drama or to use theatre in different social contexts in which Sistren and the wider cultural scene was engaged in at this time. Was there an embedded working class theatre prior to this period?

Honor: Yes, there’s a long tradition. Well, first of all, because of British colonization, which proceeded through at least two big performative institutions. One was the church and the other was the theatre. I mean wherever they were the British always brought their theatres. The British conquered Jamaica in 1655 and within a few years they opened a theatre and touring companies came through the Caribbean. So an elite theatre was important in the colonial period.

There were spin offs from that both at the level of the church, with the long tradition of church concerts, which rapidly became creolised entertainment for ordinary Black people who were in the villages and popular vernacular concerts that developed as popular entertainments.

So by the time you get to the 20th century you have somebody like Marcus Garvey who had a worldwide movement, who is using theatre and performance more generally. Not just theatre, but performance of all kinds to teach his ideas. Garvey was staging massive parades in Harlem and in Jamaica, as well as the popular variety shows that he would stage. These were ways in which theatre, that was cheap to produce, was used as a medium through which people could become politicized and become more aware of their conditions.

Conal: I think this is particularly interesting in terms of some of the ideas that you explore in a recent lecture you gave on Sistren where and you talk retrospectively about the work of Sistren with regard to the work of the Jamaican playwright and theorist Sylvia Wynter’s ideas of decolonising black women’s bodies on the level of epistemologies and the Jamaican dancer and choreographer Rex Nettleford’s ideas of ‘cultural marronage,’ which allows for a blending and hybridity of indigenous and popular cultural forms with that of a Jamaican national theatre.

Honor: That is later on when I am looking back and trying to think about how to take forward the approach developed then. I was trying to think through the implications of what performance can do when working class people do theatre themselves.

It was done in many sites, in ‘friendly societies,’ or in villages festivals where that very often took the form of satirical comedies, with a moral conclusion. There were recitations and very specifically Jamaican traditions called ‘tea meetings’ in which people would do an item, there would be a chair, and the audience would pay money to hear the item again, (which was partly how people would raise money for the community). Then in Kingston, they had a tradition of ‘varieties’ (music hall) and concerts. Then later on by the time you get to my generation, you have popular music coming in, you have the popular music industry getting off the ground and that brings with it DJs and comedy and more commodified systems of entertainment developing side by side.

Rex Nettleford was on the intellectual side of the anti-colonial struggle, as part of the tradition of anti-colonial scholarship and he was trying to figure out how to tap into popular forms which exist, but also make that part of the anti-colonial tradition and to think how we could develop forms of education which might bring that forward. So individual members of Sistren would have experienced Rex’s influence through his educational policy which provided the conceptual frame that opened the doors of the college where I worked to grass roots groups. He was at that time the chairman of the Cultural Training Centre.

So just like I wouldn’t have known that Matthew Arnold or some of these British colonial figures would have had an important influence in the schools that I went to, as a child growing up in Jamaica, it still would have had an effect on my education. I didn’t know anything about Macaulay until I did my PhD, for instance, or how this (Macaulay’s memorandum on education in India) had an effect on the kinds of schools that were allowed to exist in the British Empire.

Rex Nettleford and Dennis Scott (Jamaican poet and playwright) were Jamaican artists and writers that very important for us at that moment, because they were trying to think through how you decolonize education in practice in the Caribbean – given what we had inherited, what had been resisted and all the contradictions that people lived in and through as a result. But there were also other influences, Freire as a scholar theorized educational praxis as part a broader social movement that involved a politics of fighting for particular changes in unequal societies. All the social movements of the moment were interconnected and although some of the women’s organizations had different emphases to others, we were all somehow connected through trying to make sense of how to decolonize, how to redistribute material wealth and how to think about gender in relation to class.

So there were three components and because race and class are so interconnected in the Caribbean and elsewhere it also necessarily had a racial element, though at the time We were not so good at developing a language for talking critically and broadly about race alongside these things at that time. That has come later. it was not articulated as it is now. It’s the kind of hindsight thinking that we can do now, when we’re trying to articulate and rethink what happened and reframe it. What was essential was that on the ground we were trying to create this popular language for doing education that was outside of a colonial terrain that had failed. To rethink that in dialogue with the social movements to make change.

The academic Gail Lewis, formerly of Brixton Black Women’s Group, said that the importance of Sistren was the fact of their existence, what was important was the fact that there were these women in the Caribbean who were doing this kind of work and how that had a big influence.

Conal: I think even a brief quotation such as this bears witness to the resonance of Sistren’s work for the Afro-Caribbean diaspora and in particular the black feminist community here in London, in the context of their own activisms and allied activisms of the 1980s as well as those of the present.

Thank you so much for this brief introduction to Sistren Theatre Collective, Honor.

It’s been fantastic to consider how at the present work from the archive can develop intersecting views on survival on screen that help us to think about tools for the wider context of the COVID-19 pandemic, in terms of how artists, performers and activists have worked in the past to shape the future.

Interview with Lana Finikin, Kingston, Jamaica, June 2020

Conal: I saw Sweet Sugar Rage about 11 or 12 years ago, when it made a big impression.

In terms of the online exhibition Picturing A Pandemic and the place of Sweet Sugar Rage within this, this is a project where in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic I’m seeking to bring together artist’s and activist’s images of survival on screen and when I started thinking about this project, Sweet Sugar Rage came to mind.

I’ll just repeat the thoughts I shared with Honor last night…

I think it’s a very powerful work, but I think it’s also a very generous work in terms of how it shares its theatrical processes, its learning and its politics with the audience and that’s imbued in the work of Sistren and the educational role that Sistren had as a theatre collective in terms of educating the performers and the audience, and by extension, the video audience, who watch Sweet Sugar Rage.

I’m interested in thinking about this in terms of the politics, the polemics and the culture of the time, as I’ve discussed with Honor, but also taking this up to the present and thinking about the education and community work Sistren and GROOTS Jamaica, the current advocacy and community organisation that you lead, are doing now in the context of Jamaica’s current social and political priorities.

Also given the renewed interest in decoloniality not least at the current moment in terms of the BLM protests that we’re seeing, but also in the context of COVID-19, what it means to look at a work like Sweet Sugar Rage at the present moment and what it means for Sistren as a collective in terms of your own history.

Lana: I see the coming together of Sistren as a collective within the Manley era, and in that context based on what is happening now, as similar to what used to happen in that period. The Jamaica Labour Party government that’s in power is like a replica of what was happening in the 1970s and 1980s. It’s just that now it’s more modern and they are using a modern way of dealing with inner city persons or rural persons.

For instance, since this government came to power they came in on a promise that they would cut crime and if we brought them in, we would be able to sleep with our doors and windows open and yet lately they have been using state of emergency powers as tools to deal with crime and violence.

The persons who are mostly affected and impacted are poor inner city young men and poor rural young men who are locked up for days or even months without any system in place that would allow JPs and lawyers to access them.

Conal: So, they’re not given legal representation, or they’re not charged with anything… It sounds reminiscent of the internment methods used through emergency powers during the 1970s in Northern Ireland when people could be arrested and placed in prison without charges or were even tortured.

Lana: They have not been charged and some detainees have died under the state of emergency system…

It’s a way of controlling the country to claim that they are controlling or holding down crime but what has happened is that the ones killing and causing mayhem will move from the parish where there is a state of emergency into another parish where there is not and when that gets too hot they keep on moving. So, it’s almost the entire country now under a state of emergency. It’s an all-island state of emergency they have put in place.

Conal: And when did this start? When did the state of emergency start?

Lana: Since the government came into power So it’s about three years now.

Conal: And how does this make daily life? Are there curfews and how do you negotiate that?

Lana: …And the curfew’s on top of it now… That’s to do with COVID-19. The curfews are at different sporadic moments, and when there’s a spike in the cases they’ll drop a curfew in that particular place, or, they will withdraw it and put on an all-island curfew.

So basically, what COVID has done with farming in particular impacts most upon women. Women are the ones who are feeling the impact because schools are not open and they’re doing online teaching. So there’s only one phone or one tablet to the household perhaps and one that the parents might already have to use for business.

There are a lot of other things happening for the farmers as well… For instance you know sugar is no longer pivotal in Jamaica… Sugar is now downsized and lots of persons have lost their jobs. And so a lot of these women who worked in sugar have turned to farming and so they can’t farm, or if they do farm they can’t sell their produce.

Firstly because of the curfew and secondly even if they can get their stuff from where they are to Coronation Market, the main market in Kingston, since yesterday part of this has burned down following shooting between police, soldiers and Tivoli Garden men. So, vendors might not have space to sell their produce.

Thirdly what the government has done and some local authorities, councillors and mayors and others have been working with farmers to do, is to set up farmers markets within their different parishes. But what is happening is that the goods are being sold at less than their market value and they are being told that they should be lucky to earn something instead of the produce being rotten and thrown away.

So those are the kind of issues that the farming fraternities are having, but more so women who are farmers. Rural women have been doubly impacted, because they have kids they have to stay at home and they can’t go to the farm and when they do go, they don’t have water to irrigate the produce that they’re producing, and other stuff like that.

The other issue is that persons used to be able to talk about these issues and call out the government on issues that they deem to be corrupt, or as not adhering to the constitution etc, but people are now too afraid.

The media who should be the third estate, who would make the government accountable, are no longer doing that. They are praising the government for everything that they’re doing and not doing proper investigative journalism, they’re just printing whatever press release comes to them.

The opposition party is trying to call them out but if they try to call them out, they are told, you used to do it too; it’s like Trump and Obama. If you call them out, they say: ‘…the People’s National Party used to do it too…,’ or, ‘…They were 18 years in power, they have not done anything and this government is now doing what needs to be done…’

At Sistren we have been working with a group of women from ten communities across Jamaica’s urban and rural states: Clarendon, St. Catherine, Kingston, St. Andrew, Manchester and St. Mary and others and they are frontline workers for us, because they’re the ones who are out there now, working with their local authorities working with the Ecology Development Council using a safety audit tool that we train them in.

They do safety audits of their community, so they are using the same tool to assess what is happening on the ground to grassroots woman, elderly women, children, and disabled women who are being abused because of now staying at home when the men can’t go out to do any hustling. They have to be at home and that is impacting on community groups.

Conal: Is this all happening online?

Lana: We set up a WhatsApp group with them. They will report what is happening, they will send pictures, they will call and let us know. They are doing a soup kitchen, they are doing masks, they are working with councillors and local authorities, giving out care packages which include food and sanitization to wipe and disinfect.

Conal: Are these groups that already have a working relationship with Sistren or did you identify them as groups that were more at risk?

Lana: Almost ten years we have been working with them. The ones working in rural areas will use the products they have and make packages and give it to elderly persons as well as young mothers and community women; farm produce, vegetables etc. And the ones who aren’t in Kingston and Portmore will get packages from their council and the municipality and give it to them in person. They also help the elderly to seek out their pension or take them to get their medication.

Conal: So, it’s leaning more towards a community care model than a cultural model?

Lana: Right, that kind of stuff basically, they are doing… just doing what it is that we have to do and trying to see how best we can cope in this situation. Because the government are out there using COVID-19 as a campaign tool.

So, for instance if the women are in our community and an MP is a member of the PNP, they might not be able to get resources from them. They will have to use their own money to purchase stuff for other people and at the same time for themselves, those are the kind of things that are happening.

Crime and violence are up and persons are being killed. In the last 24 hours I understand that about 20 persons have been killed in shootings etc. We have the state of emergency and a special operational zone where they claim that they’re going in and doing work with these communities. They say that people are moving away from scamming and that they fix up the community and give them a better living.

But the persons in the community are saying nothing is happening. That they come and they’re doing counselling every once in a while, but the lives of these persons have not changed and the community has not changed.

Conal: On multiple levels it sounds like a really extreme situation for a lot of people.

Lana: Right. There are persons who do not abide by the curfew laws because they do not trust the government.

For instance, in St Catherine, we got locked down for 20 persons (falling ill) in one of the call centres. (In early May reports circulated of a spike in Coronavirus in St. Catherine centring on Alorica, a call centre employer). But yet when we move up to 220 cases we will open back up, and people are saying what is going on?

People are questioning their conscience because the authorities are not telling the truth or as the cases are climbing, or even if they’re not doing testing, for instance, they’re opening the economy. Yet still, the tourists that are coming are not going to be quarantined, they’ll test them but the residents who are returning to the country have to be tested and quarantined for 14 days. What sense does that make?

Conal: There are similar arguments here in the UK and even for those who supported the Government in the last election there seems to be an erosion of trust, many people are getting very frustrated with the measures, which itself is a public health risk. From the start there have been a lot of very contradictory messages, double standards and u-turns, now most recently on schools re-opening and then not re-opening.

So, on one hand, the government are trying to relax the lockdown measures, and encouraging people to take exercise for as long as they like, go on day trips in England and in just over a week to open non-essential shops. On the other hand, they’re criticizing Black Lives Matter for protesting and although I agree with social distancing measures I think, well, what’s the main difference between people socially distancing on a beach with no masks, as widely reported, and people socially distancing with masks on a march, which is also widely reported? In practical terms how different is marching on a scale of risk to sitting surrounded on a beach? The notable difference from the government’s standpoint seems to be when people appear to question their authority…

So there are insidious ways that people are being told what to do in ways that are politically motivated in terms of how this fails to take into consideration the politics of who bears the greater risks of the pandemic, who is struggling under the racism pandemic and the risks they are forced to take to have their voices heard. This is made clearer by the fact, that when people go along with what the government wants them to do, leisure and shopping by contrast with protesting, we’re told that one’s okay and the other is really not.

Lana: It’s a similar thing in Jamaica, everybody’s afraid of going out and protesting because if you go to a protest you are seen as fighting against the government. If you put something on Facebook and call out the government and ask questions, you’re told that you are a PNP opposition supporter because you’re questioning things. If you ask any questions you are being trolled and called names.

Conal: Yes, so public debate is closing down. Can you foresee a role for culture at the current moment? I mean, there’s been a lot of discussion I suppose in the UK about the role that culture can have as a way of keeping people connected and as a way of challenging authority.

Lana: It can but it’s a challenge because one of the things that’s impacting any kind of theatre are things like Netflix. You yourself have to have the money because the private sector are not funding cultural activities anymore, because they’re into making money. At the bottom they say what can you do for us? If they look at what it is that you’re doing and they don’t like it or it’s not in line, or is speaking out against certain issues it doesn’t get funding.

It is you that sponsors costs for electricity, the costs for renting a venue know, the cost for doing the kind of cultural work that needs to get done. It’s very, very exorbitant. A lot of persons instead of doing theatre now what is happening is that a lot of practitioners are going into schools and teaching and getting students ready to enter the Jamaica Development Commission Festival that it is every year. Well, this year it won’t happen because of the COVID-19.

Conal: There’s a really odd thing has happened here because as a consequence of the financial crisis in the late 2000s, a lot of museums and galleries and cultural organizations lost funding and one way that they cut corners was to cut a lot of education and outreach work. And it’s now precisely this area of work, to say little about social and community work, that institutions are looking towards to try to keep their activities running whilst galleries museums and theatres remain closed. I can’t help but note a certain irony.

Just to briefly go back, when you look at Sistren materials from the 1980s and early 90s, what relationship do you have to that material now?

Lana: Which materials?

Conal: Well, I suppose Sweet Sugar Rage but also other documents of Sistren’s activities.

Lana: Well we had a fire in 2004 and a lot of our material, practically everything, burned up.

Conal: I didn’t know that, that’s a real shame! Do you have copies of the videos even? Do you have even have a copy of Sweet Sugar Rage?

Lana: No, we don’t, we were on a drive to try to get back certain stuff. I don’t know if Honor has gotten any of those? We got back some magazine that we used to produce, it’s now in the Library of Trinidad, Fort of Spain and the University of West Indies library and they’re online. That I have done; but that was a project by itself.

We’re trying to ascertain how we can get back copies of the stuff that we had and put that together. And as I said to somebody, it’s not wise to get back our own copies if we can get back up copies that we can can store somewhere so we can all have access to them.

Conal: For younger people and new audiences so they can research your activity as well.

Well, thank you so much, Lana, this has been such an enlightening conversation. I would like to re-express my solidarity with your work and all the extraordinary efforts you’re doing to help all the impacted communities during the emergency measures and the COVID-19 pandemic in Jamaica. It’s really inspiring work and I think it’s important for me and for the project to link up some of these recent events and such an inspirational and important history as that of Sistren with the screening of Sugar Sweet Rage.

So thank you so much for taking the time.

About Honor Ford-Smith

Honor Ford-Smith is Associate Professor in Cultural and Artistic Practices for Social and Environmental Justice, at the Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Canada. Her publications include 3 Jamaican Plays 1976-1986, Kingston, Paul Issa Publications; Lionheart Gal: Life Stories of Jamaican Women, (with Sistren) Kingston: University of the West Indies Press; and my mother’s last dance, an anthology of poems. Toronto: Sister Vision Press. Links to her current work can be found below

Research: Memory, Urban Violence and Performance

About Lana Louise Finikin

Through the creative arts and continuing advocacy work Lana Louise Finikin has led Sistren Theatre Collective for over 20 years. Since 1977, Sistren has used street theatre to promote discussion about community safety and grassroots organizing, highlighting gender-based violence, crime prevention and HIV/AIDS through community mobilising and development. This uses the creative arts as a tool for social change for the discussion and analysis of gender-based violence and to provide solutions through organisational networks. Lana has served as a project coordinator, coach trainer and facilitator for GROOTS Jamaica, emphasising safety in cities and communities through Local to Local Dialogues and implementing safety audits. Lana has a leading role in monitoring and reviewing progress and challenges in the implementation of global development policies and commitments such as the Beijing Platform for Action, the UN SDGS and the New Urban Agenda and in mainstreaming a gender perspective and women’s empowerment in UN activities through initiatives and programmes such as Safe Public Spaces for Women and For All and Safe Cities + 20: Public Space and Gender. In 2012 Lana was appointed to the Caribbean Civil Society organisations and networks Committee and received the autorun Otto Rene Castillo Award for Political Theatre from the Castillo Theatre in New York. Lana is Vice Chair of Huairou Commission Governing Board since 2018

Link to GROOTS Jamaica:

https://huairou.org/