Watching Sylvia Kristel slowly smoke a cigarette, I think of how little the Dutch actress and model has changed since the erotic films for which she was first known in the 1970s as Emmanuelle. Still the same gestures that I remember, and the same lean frame and inscrutable gaze. In Manon de Boer’s film portrait Sylvia Kristel – Paris (2003) the camera is equally inscrutable for the lack of drama in its fixed framing of Kristel’s distinctive face, where all movement is focused on the minimalism of her minutely shifting gaze and the movement of her hand to her mouth as she smokes. Kristel’s image (filmed in Los Angeles) bookends shots of Paris which accompany her voice as she remembers her time spent there, her remembrances carry, disembodied, over panning images of the city as a blur of buildings, aerial and close by. Whilst her image is separated from the recollections she voices, this is not to suggest that images of the actress are silent. Instead de Boer amplifies the sounds of her breathing, as she smokes without speaking, marking time with her act of remembering in inhalation and exhalation.

I recall how some of the first writing on cinema addressed the potential of the close up on an actor’s face to unlock previously unattainable depths of performative expression. How Bela Balazs in the 1920s wrote of the unique ‘microphysiognomy’ opened up by cinematic optics, which through its properties of magnification ‘seemed to penetrate to a strange new dimension of the soul’.’[1] De Boer’s use of the close up is also concerned with revelation, but it is the play of memory on Kristel’s image, rather than ‘the play of the features’[2] which transports the viewer. Instead of reverie, here de Boer is interested in how other resonances might be exposed in the fissures and gaps in cinema’s smooth sound/image suture: those which allude to its status as a time machine, registering cultural memory alongside the personal. In Kristel’s face, we read a complex history of the late Twentieth century’s libertarian impulses in the wake of ’68, where the figure of Emmanuelle expresses the tensions between sexual freedom and feminist critiques of pornography. Her image also evokes personal memories for de Boer of her own ‘70s childhood, when Kristel’s image was most prevalent in cinemas and on television screens. These entwined inscriptions of personal and cultural time animate Kristel’s image in Sylvia Kristel – Paris.

Viewed in the context of her work since, Sylvia Kristel – Paris offers a key to some of the concerns that continue to compel de Boer’s practice, apparent in the works now included in the LUX collection. Whilst the film’s aesthetics of portraiture might correspond to the formal brevity of Warholian screen tests, the film is less a study of cinematic iconography, and more intent on dismantling cinema’s image and sound hierarchies – in order to draw out different readings and versions of events. Sylvia Kristel – Paris results from several interviews between artist and actress over a two-year period, where the cities in which she lived provide a point of focus around which other narratives of her life both personal and private might circulate. The film comprises two interviews separated by a year and with the last played first. For de Boer: ‘Her stories refer to a collective memory of the seventies / eighties, on the other hand she always gives a different version, which reveals, in the differences, something of her as individual. What interested me most was the working of her memory.’[3] But in the manner of the unreliable witness, and in the gaps of forgetting as well as remembering, Kristel’s memories in de Boer’s film shape up a different reading of passing time from the singularity of a conventional biography or historical chronology. The actress’ iconic presence becomes incidental to the nuance and texture of history in which she is enmeshed, registering her as a presence and participant in the wider contemporaneity of 1970s culture and experience. The panning images of Paris which accompany Kristel’s remembrances interrupt the camera’s focus on her face, as if to signal quite literally, a movement from the particular to the collective, and to a history happening elsewhere alongside Kristel’s own. The actress provides the point of entry through which de Boer is able to address profound questions of itinerancy (as Kristel moves across cities and countries), celebrity, gender, family, loss and the culture of cinema itself.

Resonating Surfaces, Manon de Boer, 2005

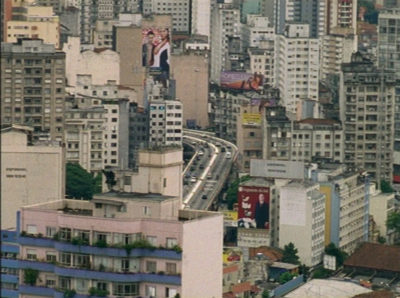

The use of portraiture as a form of historical evocation, and register of cultural time passing, is a recurring characteristic of de Boer’s work. In Resonating Surfaces (2005) Brazilian psychotherapist Suely Rolnik – Kristel’s similarly iconic contemporary – recalls her life in Sao Paulo at the time of dictatorship and her relationship with Deleuze as an émigré to 1970s Paris. Here, Rolnik’s arresting image, often in shadow, is juxtaposed by aerial images of Sao Paulo’s high rises: what Rolnik remembers as the ‘grey’ city which provides the accompanying – or competing – character of the film, and allows de Boer to access the enduring trauma of the Brazilian dictatorship through a remembrance as fragmented and elusive as Kristel’s. According to de Boer: ‘it’s about trauma and how a system of power, like the dictatorship in Brazil at the time, can cut off the access to the voice (her voice in the Portuguese language) and by this to vital energy.’[4] As with her portrait of Kristel, the complex correlation between singular experience and history’s wider currents and contingencies is delineated in the subtle correspondences and points of dissonance which de Boer orchestrates between image, voice and music: the timbre of Rolnik’s voice, resonant with the cadences of the Portuguese language; the instability of de Boer’s analogue film images, and the emotive pitch of female voices in song, those of Lulu and Marie from Alban Berg’s operas Lulu and Wojzzeck, which Deleuze had recommended to Rolnik as a way to understand her fractured past.

These two films form part of a trilogy which De Boer completed some six years later with her portrait of American percussionist Robyn Schulkowsky, in Think About Wood, Think About Metal (2011), and in which she further dismantles the synchronicities of cinematic image and sound, by conceiving the film’s organisation of image, sound and voice as ‘autonomous spaces which connect through rhythm and flow’.[5] The musician’s recollections of her friendships with Cage and Morton Feldman, her experience of Cologne’s music scene of the 1980s and the development of her music, are accompanied by images of a contemporary Cologne’s industrial margins in the traffic of trains and telegraph wires, and juxtaposed by close ups of the bowls, sheets of metal, gongs, hammers that make up her percussive repertoire. Unlike de Boer’s earlier portraits, it is the musician’s hands rather than her face which are pictured in close up, as if to offer a further expression of the ‘microphysiognomy’ which Balazs believed the film camera could reveal. As they strike and tap metal, the sinews of Schulkowsky’s fingers seem alive with an intensive mode of listening, attuned as much to resonances from her remembered past as to the vibrations emitted from her instruments. I’m reminded of the method of ‘deep listening’ which the composer Pauline Oliveros developed, defining it as ‘listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing.’[6] Advocated as a form of practice, and ‘a heightened state of awareness [that] connects to all that is there,’[7] Oliveros made a distinction between hearing and listening: seeing the former as happening involuntarily, whereas the latter ‘is a voluntary process that through training and experience produced culture.’[8]

I’m struck by the link that Oliveros makes between listening and culture, what she refers to as ‘directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action’. Whilst deep listening might indeed precipitate culture through new musical forms and communities for its makers and audiences, her words suggest that, on a more profound level, it is able to access the deeper resonances of time passing as history, culture and experience: heard perhaps in the musical timbre of Rolnik’s voice, or the thrum of Schulkowsky’s fingers on metal. De Boer’s films operate on this frequency of acoustic attentiveness. Think About Wood, Think About Metal also marks de Boer’s continuing exploration of how to represent the intimacy of musical performance, and the acute attunement that occurs between musician and instrument during the process. With the exception of Jayne Parker, few artists have sought to represent on film the complex process of interpretation and attention related to making and experiencing music. Works such as Presto, Perfect Sound (2006) and One, Two, Many (2016) are portraits of the absorption with which the violinist George van Dam and the flautist Michael Schmid respectively, approach their interpretations of Bartok or the strenuous exercise of circular breathing. At times in Presto, Perfect Sound, for example, it becomes difficult to separate musician from violin as they merge in a concentrated act of instrumentalization, magnified by the camera’s close gaze on the act of performance. And yet, for all this apparent symbiosis, the vibratory inflections and shifts in tension and pitch depicted on screen are not necessarily what is heard, but a collage made of five different recordings of the sonata, to which the image track was edited afterwards. This realignment is imperceptible to a viewer trained on expectations of a certain cinematic image/sound hierarchy, and yet it could be argued that a different rhythm and intensity is experienced through De Boer’s tacit process of editorial reversal.

Think About Wood, Think About Metal, Manon de Boer, 2011

As Schulkowsky and van Dam’s dancing fingers indicate, listening is portrayed as a performative and embodied action, not only for the musician but in the numerous portrayals of the listener which can be identified across de Boer’s films. Representations of listening, where they occur at all in cinema, are driven by narrative demands; an ear to a door to catch a secret, perhaps, or listening during an exchange of dialogue. For de Boer, as for Oliveros, listening is a more complex and embodied experience: reflective as well as responsive. As de Boer has said: “I find it fascinating to watch the face of someone who is reading, playing music or thinking, because these are often moments when people seem to forget their ‘social face’, being so concentrated on an interior activity; moments in which a mental space is reflected on the face – this surface between inside and outside.”[9] It is this portrayal of an intense concentration directed elsewhere that is common to many of the people depicted in de Boer’s films. As Oliveros’ concept intimates, listening is not only done with the ears, but with all actions of body and mind. Rather than passivity, de Boer’s subjects are lost in tasks connected to time as an unfolding mode of apprehension through listening, making, reading, remembering. Often there is a circular or repeated structure, where the performer in question reprises an action for the camera, or where the film-viewer is required to re-view a sequence similar but – as Sylvia Kristel – Paris has already shown – not the same. Dissonant (2010), for example, might be seen as a form of memory game, where the dancer Cynthia Loemij first listens intently to Eugène Ysaÿe’s Three Sonatas for Violin. Keeping in time with a score internalised through memory, she performs into the silent space of the rehearsal room. In the intensity of her movement the viewer witnesses a form of embodied listening, where the music is more powerfully evoked in its absence. The sounds of her performative exertions, which might usually be hidden beneath the non-diegetic sweep of the soundtrack in cinema, are made audible instead. Stripped back to the sounds in the room at the time of the film’s recording, the thud of Loemij’s feet, her breathing and the whirr and click of de Boer’s 16mm camera, assert an alternative musical score.

It could be argued that de Boer uses the film medium as a means of deep listening, eschewing the clockwork linearity of the analogue film camera’s mechanical functions, to repurpose it as a tuning fork to temporal frequencies less visible and audible. As Oliveros said: ‘Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, or one’s own thoughts as well as musical sounds.’[10] It’s a sensitivity to surroundings which de Boer explores in Two Times 4’33” (2008), probing a performance of John Cage’s famous composition, and marking its eponymous time frame in the panning movement of her camera, as she circles the performer at his silent piano. De Boer’s film is both a tribute to Cage’s far reaching ideas about sound and silence, at the same time that it enables her to continue to probe the fissures in film’s sound and image synchronicity. Cage’s concept of ‘polyattentiveness’, which ‘dissolves the difference between “art” and “life”’[11], might bear comparison to Oliveros’ deep listening for its attunement to the multi-sensory fields of sound and image on the periphery of a performance. The first movement of the film frames the pianist Jean-Luc Fafchamps in a mode as attentive as any of de Boer’s subjects, marking on a timer the intervals (at 1’40”, 2’23”and 30”) which feature on Cage’s score. Yet Fafchamps’ performance is accompanied by the incongruous sound of windswept trees and rain, an amplification of the sounds from a stormy day outside the windows of the Brussels studio where the performance takes place. In the second movement of the film, de Boer’s panning camera reveals the blustery landscape through the glass, along with the immobile audience of young musicians from The Performing Arts Research and Training Studios (PARTS) who are listening. In their varying postures or the direction of their gazes, de Boer explores again the figure of the listener – alive to the nuances of contingent sound, at the same time that they appear absorbed in their own introspections. Yet, the only sound that accompanies this collective portrait, and the stormy drama outside, is the punctuating strike of Fafchamps’ timer, already seen in the film’s first movement.

De Boer’s desire to prise apart the sound/image falsehood so central to cinematic verisimilitude could be seen as generated by curiosity rather than critique. How might different variations on synchronicity open out new potentials in the image? The beauty of Two Times 4’33” lies in how a simple switch in synch between what is seen and what is heard draws attention to the act of listening, alongside the sounds themselves.[12] Like all of de Boer’s films, Two Times 4’33” invites different forms of embodiment and participation in her subjects, and here in the viewer too. Finding ourselves mirrored in the silent listeners on screen, Two Times 4’33” elicits a level of sensitivity to sound and image relations rarely demanded in cinema, encouraging a mode of listening attentive enough to pick up the deeper reverberations of history and lived experience, alongside more local acoustic contingencies.

[1]Bela Balazs, Theory of the Film (Dennis Dobson Ltd: London) 1952, p65

[2]Ibid 64

[3]Manon de Boer, quoted in Narkevičius and De Boer meet during Film Festival in Rotterdam by Manon De Boer and Deimantas Narkevičius, 2004. Accessed August 15th 2020, http://janmot.com/text.php?id=14

[4]Manon de Boer, interview ….3 Newspaper Jan Mot, p127

[5]Ibid

[6]Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (to Practice Practice), 1999.p1 https://soundartarchive.net/articles/Oliveros-1999-Quantum_listening.pdf (accessed 10.09.2020)

[7]Ibid

[8]Ibid

[9]‘In Dialogue: Manon de Boer and Jayne Parker, Wed 7 Oct 2015’, LUX website: https://lux.org.uk/event/manon-de-boer-and-jayne-parker-in-dialogue (accessed 12.09.2020)

[10]Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (to Practice Practice), 1999.p1 https://soundartarchive.net/articles/Oliveros-1999-Quantum_listening.pdf (accessed 16.09.2020)

[11]Quoted in Henry M Sayre, The Object of Performance: The American Avant-Garde since 1970, University of Chicago, 1989, p106

[12]For a detailed and insightful analysis of Two Times 4’33”, see Eu Jin Chua, ‘The Film-work recomposed into nature: from art to noise in four minutes and thirty-three seconds,’ Moving Image Review and Art Journal (MIRAJ), Volume 1, Number 1, 23 January 2012, pp. 89-96, Intellect: Bristol.

Lucy Reynolds has lectured and published extensively, examining questions of the moving image, feminism, political space and collective practice through her writing, curating and art projects.

Her articles have appeared in a range of journals such as Afterall, Screen, Screendance, Art Agenda and Millennium Film Journal, and she has curated exhibitions and film programmes for a range of institutions nationally and internationally, from Tate and MUHKA, Antwerp to the ICA and the South London Gallery. She has contributed chapters to publications on moving image histories including David Curtis, Duncan White (eds) The Expanded Cinema Book, Afterall/Tate publications, 2010; Bridget Crone (ed) The Sensible Stage: Staging and the Moving Image, Picture This publications, Bristol, 2012 (2nd ed 2018); London Art Worlds: Mobile, Contingent and Ephemeral Networks, 1960-1980 (eds. Jo Applin, Catherine Spencer, Amy Tobin), Penn State University Press, 2018 and Other Cinemas: Politics, Culture and Experimental Film in the 1970s (eds. Sue Clayton and Laura Mulvey), IB Tauris, July 2017.

As an artist, her films and installations have been presented in galleries and cinemas internationally, and her ongoing sound work A Feminist Chorus has been heard at the Glasgow International Festival, the Wysing Arts Centre, the Showroom and The Grand Action cinema, Paris. She is editor of the anthology Women Artists, Feminism and the Moving Image, co-editor of Artists Moving Image in Britain since 1989. She is co-editor of the Moving Image Review and Art Journal (MIRAJ).