It’s 1991 in Vilnius, and an enthralled crowd is gazing on as a legless Lenin statue, swinging from a wire, swoops around in the air above them like an absurdly heavy ghost (and this is perhaps a good way of describing the dead leader’s presence at this point).

Filmed in Lukiškės Square on the day the statue was removed, footage of this event was widely was circulated across international news media, a dramatization of one of many symbolic endings to the Soviet Union. In Deimantas Narkevicius’s video Once in the XX Century (2004), Lenin’s ghost statue is reinstalled. Recutting the action in reverse, Narkevicius shows us a violently enthusiastic crowd cheering a statue as it is paraded on the back of a vehicle, and raised into the air to then swing uncannily into place, as Lenin is reunited with his legs in seamless fashion. And the crowd goes wild.

Once in the XX Century throws into relief the absurdity this scene as a potential event – the public barely ever gets as wild about installing authority as it does about dismantling it. But more deeply, the video also reveals a moment of breakage in the country’s history, mirrored in the ruin-image of a pair of calves and feet stranded on a plinth with no body or head. Moments of dramatic political violently break the future open, to reveal an unnervingly undefined limbo. However a violent break with the past such as this – when it is open season on the symbols of the powers just ousted – is also moment of groundless suspension.

Much of Narkevicius’s moving image work, which became his primary medium in the early 1990s following an early training in sculpture, focuses on this period of intellectual confusion following the breakup of the USSR, a moment in which the artist was formulating his own practice. A significant number of works pay close attention to the remnants of monumental sculptures from the Soviet era, dominated by an officially approved Social Realist aesthetic, registering (through superlative editing), the dampeners on creativity and expression in such conditions, whilst simultaneously acknowledging that the bargaining game that Eastern Europe was entering, trading personal freedoms for other losses and gains. Narkevicius suggests that clearing away the markers of recent events leaves little room for reflection. Denial is an understandable reaction to moments of revolution and political upheaval, but it is a trauma response, which precludes deeper critical analysis. “Everyone seemed to think that removing these objects would lead to immediate changes in society”, he has remarked. Yet such objects are carriers of history as much as they symbols of oppression.

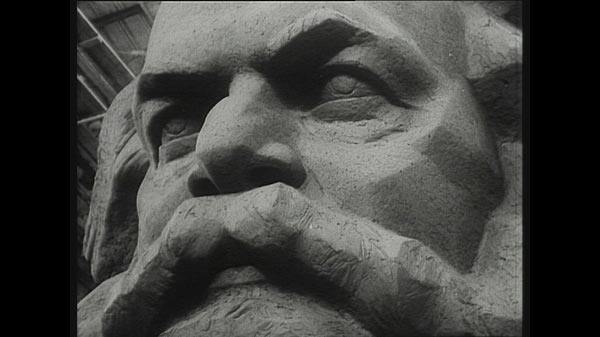

So Lithuania, like so many other states, lost an unwanted head. “Karl Marx has no need for legs or hands; his head says everything”, announces the sculptor Lew Kerbel in another work of Narkevicius, The Head (2007), entirely made using appropriated film from DDR public access television of 1960s and 70s. The central narrative follows Kerbel as he crafts the biggest head monument in the world – a giant head of Marx destined for Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz), which was unveiled in 1971, but intercut is footage of a general public doing everyday things – drinking water in the street, crossing the road, petting animals, and of children talking to camera about what they want to be when they grow up. How to freely make decisions or make art in such programmatic conditions, when ideologies shape aesthetics, which flow into public spaces and public life?

It is perhaps The Role of a Lifetime (2003) that most evocatively and thoughtfully ties together Narkevicius’s interests in the uncertainties at the heart of post-Soviet Lithuania with the implications of his own work in creating film and video. Commissioned by the UK-based organisation Art in Sacred Places, for a parish church in Brighton, this video features the voice of the radical British filmmaker Peter Watkins, known for his pioneering docudrama films Culloden (1964) and The War Game (1965), which both politicized and fictionalized the documentary form. As we hear Watkins reflect on the political and social beliefs that spur him to disrupt dogmatic forms of realism in cinema, the images on screen pan across a pencil-drawn, sylvan landscape populated by ruins of soviet monuments – statues of Lenin, Marx and so on. The sketches, made by Mindaugas Lukosaitis, depict Gruto Park, a kind of theme park to the Soviet era that exists in the south of Lithuania, which Watkins describes as either “a disaster”, or a place “to reflect on man’s unbelievable folly and inhumanity…and, sadly, the endless repetition of history.”

Watkins’s reflections on the genesis of his own work and his Leftist political beliefs are accompanied by amateur footage taken in Brighton where the video was to be shown – grandmothers and children playing with bubbles, a street market, walking the dog along the sea, the botanic gardens, and the buildings along the seafront. As in other works, here it is Narkevicius’s editing in of the quotidian and the unmonumental qualities of everyday life that complicate the material and bring it into dialogue with the misplaced authoritarianism of the dead monuments. Watkins’s attention to reinterpreting history and continually bringing it into dialogue with the present day – a resistance to pushing the past away out of sight and mind – is mirrored in the dystopic/utopic space of the sculpture park, neither alive, nor dead, but fully both. As rendered by Narkevicius the space represents the indigestible qualities of these objects, burdened by their role as icons of a past regime.

One of the important elements of Narkevicius’s work is its constant return to open, humane registers, in which political material is often seeing rested on protagonists who are both common people and curious individuals. Several of the artist’s subjects are disarming characters, which the artist draws out in various interview techniques. Early on in his career, inspired by fellow Lithuanian Jonas Mekas, the artist began a practice of conducting video interviews in order to construct his films, and yet in most cases the ‘straight’ Q&A is undercut by unusual collisions in relation to role-play. In the Dud Effect (2008), the artist’s subject is Evgeny Terentiev, a former Russian officer who served at a military base in Lithuania, which was the home to R-12 Dvina thermonuclear missiles aimed at various Western countries. Terentiev’s daily routine and military orders remain so deeply ingrained in his memory, that he does not find it much trouble to re-enact, years later, his life at the base, and to perform the sequence of actions that he would have carried out had he received orders to fire. The weights of responsibility, as history has shown, eventually fall to individual actions, yet there’s something about the ingrained memory, a lived memory that Terentiev’s training reveals – a potential line of flight into a horrific, alternate timeline which the officer himself must have envisioned countless times.

Role confusion and layering is also at play in 2005’s Matrioškos, in which three actresses recount stories of enforced prostitution as though they were the characters that they had just played in a recent television drama; the fourth wall only fully broken when one of the characters explains: “and then he killed me”, which nevertheless seems to affirm the presence of imagined violence on her body, fictional or not. Another actor, Donatas Banionis, was asked by Narcevicius to revisit his role in Andrej Tarkovskij’s Solaris (1971) for another work Revisiting Solaris (2007) to create the final sequences of Stanislaw Lem’s original text many years later. Narkevicius used photographs taken of the Black Sea coast in 1905 by Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis to stand in for the soil of a strange planet – one that curiously, in the telling, seems to become a metaphor for aging and death, as the character Chris Kelvin is embraced by a strange sea that reaches out to envelop his hand without ever touching it. The violence in all of these conversations, however, is always barely perceptible, only just grasped. There is a gentleness in Narcevicius’s treatments of his subjects, as though he is carefully broaching a conversation with them.

This somewhat tender approach on the part of the filmmaker vis-à-vis his subjects is apparent in the artist’s repeated use of children when appropriating historic footage – his focus on the way that children speak and navigate the world draws out youthful qualities of freshness and potential, though in the gaping space of the edit, between a child and the world, suggests the particular ways in which a structure can shut such potential down. A suite of recent works has focused on the youth and naivety of young men, and in particular a young guitar band (of which the artist’s son is a member) called Without Letters. Narcevicius’s music video – Ausgetraumt (2010) made for the band’s first single, sees them playing their jangly, upbeat post-rock tune in an isolated, deserted house. Their sweetly concentrated effort and lack of cynicism is picked up by the camera as they thrash out their track with intensity, creating a kind, generous portrait of naivety that can only be made by an older soul. Yet the message, once more, is in the cut. The landscape of their country – a sprawl of snowy hills and ugly roads, paints a lonely picture, and suggests that there is no one to see them. Though their fortunes have subsequently changed – they now play to large crowds – Narcevicius’s first portrait of Without Letters is an exercise in the suspension of belief for all concerned, and is a direct intervention into a country without its own culture of pop music as a form of expression. Restricted Sensation (2011), a short, fictional feature film by the artist depicting the abuse of a young gay man during the Soviet era, is a further indication that the artist’s concerns remain freedoms of the mind. In a country where possibilities were restricted, then made available, leaps of faith still have to be made. For it’s one thing to be headless, and another to be heedless. It’s in his attentiveness to the past that Narcevicius suggests concern for the future. Broken knees must be attended to.

Laura McLean-Ferris is a writer and curator based in London and New York. She regularly contributes to Art Agenda, Artforum, Art Monthly, ArtReview, Frieze and Mousse, as well as writing regularly for the Tate Collection. Recent projects Geographies of Contamination at David Roberts Foundation (2014) and #nostalgia at Glasgow International (2014). She is currently working on exhibitions that will take place at S1 Artspace, Sheffield (2014), and Cell Project Space, London (2015).