1) Emilia Terracciano

In 2015 you were the recipient of the Drawing Room Bursary Award. During your residence at the Drawing Room you used the gallery space as a studio, populating the space with works on paper, graffiti, life-size comic foregrounds illustrated with satirical scenes, free standing panels with playful’ head holes’ to encourage audience participation, as well as videos. I vividly recall your handwriting, there was a lot of it; I pored over the text you had copied out, long passages in bold, block letters, no cursive, and no joined letters. There was your fictive character the headless narrator. I remember being struck by the dada-like disjuncture you staged between writerly, textual and visual registers, and how this provoked a shift between critical, poetic, and disciplinary realms. More recently, this raw delivery of the writerly component has become vocal in your rapping and digital animations. You incorporate rhyme, rhythmic speech, and vernacular racist slurs. How has your relationship between writerly, visual, and sonic realms evolved over the years? At what point did text become sound? Part of the body and apart from the body, present yet absent, when did rapping enter the ‘picture’, animating your digital creations?

Hardeep Pandhal

It all started in 2007, the year I graduated from my BA (Hons) Fine Art degree at Leeds Metropolitan University, now Leeds Becket University. The first thing I made post-degree was a rudimentary narrative-based animation called Thug Odyssey, which I made from scanned-in drawings. This work is not widely recognised as it was received primarily by my friends. It is a fan-inspired sequel to the low-key Hollywood film Gridlock’d (1997), which starred Tupac Shakur (arguably in his most convincing acting role), Tim Roth and Thandie Newton. This motley bunch portray a drug-addicted band of musicians who embark on a tireless quest to be granted access to state welfare.

References to rap music have manifested in my work since Thug Odyssey. In professional art circuits, the reception of my work has hinged around the question of sincerity on my part, like “are you being ironic?”, or more bluntly “are you taking the piss?” [laughs]. This led me to question who my work was for, a question that still comes up a lot. Thinking about fan-art, I wonder whether I have a deep-rooted suspicion of the engineering of ‘significance’ in contemporary art, or the way in which ‘outsider art’ is recuperated for mainstream appeal. Perhaps this is why I tend to work with people outside of the art market, although the distinction between ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ has become increasingly blurred. In short, I try to make work for myself first, before editing it for contemporary art consumption, which doesn’t invariably result in a sanitised edit.

The above considerations eventually led me to write and deliver my own rap. Like most ‘first-times’, this activity started collectively with friends and was recorded in the safety of our impervious bedrooms.

My work has always been about privilege. I thought about the feedback I was receiving in regards to my references to rap in works like Thug Odyssey. These were highly revelatory in regards to questions of taste and social reproduction. If one is looking for it, there’s plenty of high criticism around hip-hop culture. The writers Roy Christopher, Henry Louis Gates Jr and Imani Perry come to mind immediately. Also, for those who are particularly receptive to Eurocentric attitudes, one could seek ancestral sanctity in the knowledge of the medieval tradition of Flyting, a ritualised and theatricalised form of verbal sparring (in rhyme). Some scholars believe Flyting was transmitted and adopted by African slaves from Europeans during the Atlantic slave trade, rather than the other way round!

As a gamer perhaps I am more reliant on haptic, visual and in-direct feedback. Keza Macdonald and Jason Killingsworth invoke ‘self-determination theory’ to articulate the benefits of play in their book You Died – a companion to the gaming franchise Dark Souls which I am currently playing. This game attributed to the recent popularisation of the gaming genre known as ‘masocore’, games characterised by ‘tough but fair’ mechanics that require the player to die an inordinate amount as part of the learning process:

‘Understanding the psychology of Dark Souls and what it does to our brains is the key to understanding why its version of difficulty is so rewarding and absorbing, where difficulty in other games is just frustrating and off-putting. One of the key psychological models behind human motivation is called self-determination theory, which posits that for a person to persist and feel motivated by an activity, it has to satisfy three different needs: mastery, autonomy, and relatedness. Dark Souls offers mastery in spades, in that you always feel like you are getting better. Autonomy is the feeling that you are free to make choices, and that those choices are meaningful, which Dark Souls also accommodates. And finally, there’s relatedness: the feeling of connectedness to people. That’s one of the things that prevents Dark Souls’ difficulty from being too demoralising: it has a sense of community. You know that you’re going through it with thousands of other people, too, and seeing their messages and ghostly presences in your own game (whilst playing online) helps you feel like you’re not alone.”

Coming back to your question: At what point did text become sound? I think the relationship between the writerly, visual and sonic realms in my work can be approached by considering my preference for, and value of, elliptical modes of conveyance. Ellipsis and associative thinking are at the core of my current method. However, the associations I want to present need to be deep rooted, not purely semantic. This is why I tend to spend a long time dwelling on a particular issue or reference.

I believe tools of suggestion and persuasion are powerful and humans are highly impressionable. I often say that racism is one of the most widely practiced forms of the dark arts today [looking pensive].

2)ET

Scholar Mladen Dolar has written persuasively about voice, how for example it can give rise to forms of subjectivity, expression, and communication. She argues that when voice is automated, or produced through technological means it can sound uncanny. Voice may be a ghost in the machine, something that questions the existence of consciousness. I wondered about your digital animation Paranoid Picnic: The Phantom Bame (2018). The print ‘Autospeechola’ created by Bengali artist Gaganendranath Tagore in 1917 becomes a way for thinking about the violence, the mechanisation of speech, and in our present context, the looming threat of fascism. What drove your specific archival selection?

HP

I was drawn to the image as I was reading around histories of sectarian violence in post-partition India; Sudhir Kakar’s book The Colours of Violence in particular. Gaganendranath Tagore’s work, and specifically ‘Autospeechola’ seemed to be prescient at the time of its making. It felt like I was simply adding my spin to the countless commentaries on, and creative responses to, India’s puzzle-like constitution, as issues of disinheritance and disaffection tend to spill over transculturally and cross-generationally. From my personal experience at secondary school in Birmingham, I remember encountering more hostility from South Asian boys than white, black or East Asian boys. This was primarily due to religion, even though most classmates weren’t strict, and the cultural divide between Indian and Pakistani identity, even though all of us were born in the UK. Indian Muslims had it both ways [laughs]. I suspect these attitudes were transmitted via the family home, but I don’t think our school teachers were prepared or trained to be sensitive to these issues. The fallout of partition resurfaced in unexpected and unrelenting ways, however there were little to zero outlets for people belonging to the first generation to think through and confront it. I had quite an education in these histories of segregation, and I am now avenging the effects of partition through forms of humanising violence as a career.

I think my go-to preference to work with suggestive or elliptical text and voice in my work has arisen from the lack of direct verbal and textual communication I am able to have with my mother. Our relationship has surfaced a lot in my work to date and I suspect it will continue as she refuses to learn English and I am slow at learning Punjabi properly, if there is such a thing as proper Punjabi! I am also doubtful whether a more shared linguistic grasp will bridge the wider cultural gap between us. I have faith in associative thinking practices, which are perhaps more indirect or oblique, and therefore unsettling, than one would like. My method assists me in identifying more confidently who my allies are and those willing to engage with me humanely. The first step is to ask thoughtful and considerate questions, to be an active receiver of my work, to risk filling in the gaps.

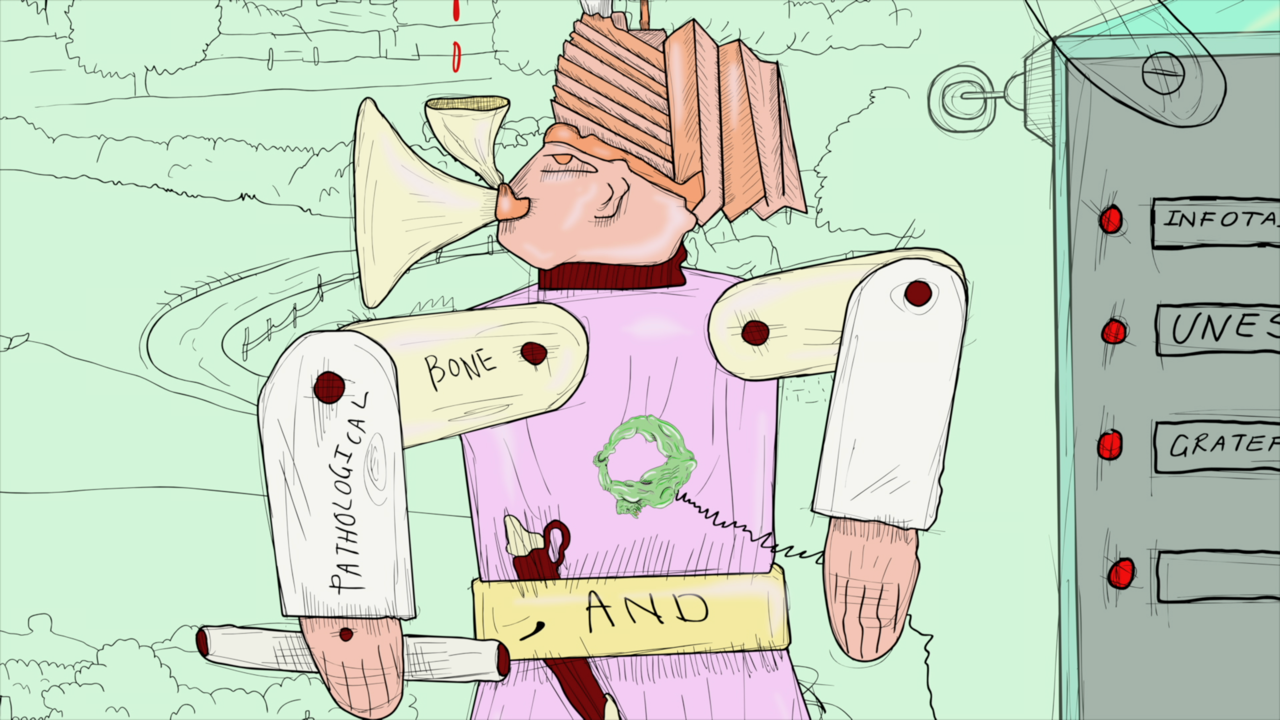

Paranoid Picnic: The Phantom BAME, Hardeep Pandhal, 2018.

I am glad you evoke the ghost in the machine metaphor. Deborah Levitt’s reading on animation, and particularly her reading of Mamoru Oshii’s film Ghost in the Shell 2, which I understand to be a post-human meditation on the ontology of dolls, might be generative here. I chose to animate Tagore’s drawing of an automaton whilst changing the textual descriptors of the buttons on the machine. The animated sequence in which the automaton appears occurs twice, but differently. This sequence is sandwiched between video footage shot in my studio, where scraps of old 2d work are ‘reanimated’ via the assistive and associative lyrical voiceover I deliver. In the spirit of Oshii’s idea, I wanted to give voice and perspective to Tagore’s automaton, a ‘decolonial ventriloquism’ if you will, but also fill in the gaps between us as artists who have overlapping points of reference, albeit at different points in history. The ‘reanimating’ imperative of this video also relates to another method that I employ in much of my work, which is dialectical play; bringing into relation seemingly oppositional or disparate forces or ideas, namely to articulate their interdependence. My work is about the process of bridging. The bridge looks like a time-laden scar rather than a clean, sanitised or forced erasure, much like the train tracks my maternal grandfather worked on in colonial Uganda.

3)ET

The evocation of the phantom, of limbs, bodies, voices in Paranoid Picnic draws attention to the equivocal nature of the acronym BAME, its performative character and perhaps also emptiness as elocutionary strategy. What are your views on this?

HP

I am currently making a short narrative-based animation which retells the moment when I first encountered the acronym BAME, which happened in an art school context. The experience was weird, and felt close to Tzvetan Todorov’s much cited definition of the fantastic in literary works, which differs slightly to the uncanny. The fantastic is more fleeting, situated in the present, rather than the uncanny, which refers to a past or known facts – such as the home which becomes inexplicable or ‘unhomely’ to some degree. For Todorov, it is a hesitation that sustains the effect of the fantastic in fiction. The fantastic ‘lasts only as long as a certain hesitation: a hesitation common to the reader and character, who must decide whether or not what they perceive derives from reality as it exists in the common opinion.’ Encountering the acronym BAME in an institutional document affected a similar sense of hesitation in me, making me doubt whether my perception of reality was common to the world as others perceived it. It made me think about constraints and how to work within them. I liken the work I am doing to ‘thinking radically inside the box’. Perhaps this is why I have become drawn to fantasy world-building broadly speaking. Layers (both literal and metaphorical) within my work assist me in conveying parallel realities that can collide, collude or collapse. You see this formally in the animation work, where multiple flat planes are arranged to convey depth and perspective to different poetic ends. The use of imperfect tense in my speech and writing intentionally adds to this effect of the fantastic.

4)ET

Happy Thuggish Paki (2020) is a rap, and elliptical auditory exploration of the English word ‘thug’, with roots in the Hindi ठग, meaning ‘swindler’ or ‘deceiver’. Nineteenth-century colonial officials claimed that Thugs committed ritualistic murders involving the strangling of travellers with handkerchiefs as part of their worship of the Tantric goddess Kali, a colonial trope that allowed the British to impose greater controls over the local population. Colonial fears surrounding the cult of Kali escalated with the rise of revolutionary movements in Bengal, especially following the ‘Indian Mutiny’ according to British historians, or ‘First War of Independence’ according to Indian historians, in 1857. Is the happy artist reclaiming the term through the lyrics? Is it a case of disrupting through voice cultural assumptions about performing heritage in Britain?

HP

I’ve always wanted to maintain a considerate balance of humanity in my work, which means keeping a wide range of emotions suspended in the worlds I am presenting, as well as speaking beyond my own subjectivity – through fictive modes. I hadn’t known about the British-Indian origins of Thugs until quite recently. Thugs also circulate in the lyrics of black American rap music, and I wondered if I could build an exhibition around this association, as references to both rap and the British Raj already circulate in my work. This exhibition was called Confessions of Thug: Pakiveli. A short visual introduction to this exhibition can be accessed here: https://vimeo.com/425831444 or www.hardeeppandhal.com

Confessions of a Thug: Pakiveli took its name from the pulp fiction of 1839 of the same name by the Orientalist writer Phillip Meadows Taylor. The exhibition’s subtitle ‘Pakiveli’ referred to one of my rap monikers, adapted from an alias of the late rapper 2pac, ‘Makaveli’.

Although opinion is divided, many believe that Thugs were politically sensationalised by the British to appear innately criminal. The fiction Confessions of a Thug mentioned above is exemplary of such sensationalism. It was adapted from real British criminal records and took the form of a deposition of a supposed Thug. In the exhibition I drew analogies between the racialised myth making of such fictions and modern forms of proscription, such as the predictive policing and racial profiling that we are familiar with today.

Bridging different contexts, I approached this exhibition as an exaggerated deposition, connecting methods of associative thinking and playful ellipsis akin to rap production across a wide range of subject matter and media formats, including rap itself.

The Indian mutiny and the ruthless retribution it led to was spurred by rumours based on fears of contamination, the fear amongst sepoys of the forced implementation of animal fats in the loading of their ammunition, which would have been sacrilegious, and of the fear amongst the British that memsahibs (white women) were getting too close with the natives and distracting white officials in their business. I should add that there are examples of fiction written by memsahibs that are somewhat sympathetic to the natives’ plight, which I’d like to adapt into a film in the near future.

In 2010, I started a series of drawings based on sepoys after learning about their roles in the two world wars. More recently, this repressed history has become more and more public, in exhibitions, monuments and even in blockbuster films, such as 1917. It’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand it’s uplifting to see people that look like you being remembered or celebrated in official history. On the other hand, it’s a sobering reminder of the manner in which racialised subjects have been instrumentalised in Britain’s broader and ongoing project of redeeming itself from its own ruthless past. Paul Gilroy diagnosed this condition as ‘Post-Colonial Melancholia’ in his book of the same name.

Happy Thuggish Paki, Hardeep Pandhal, 2020

5)ET

How do you see your work in relation to recent vocal calls for ‘Decolonising’ the art world? Specifically, how do you respond to institutions which frame your work as ‘decolonial’?

HP

It’s an ongoing quest to be frank and there are no simple answers. I try to imagine what it’s like for a person who does not share a similar background as me to see my work. I am starting to believe audiences that do share a similar background to me exist in contemporary art contexts too. I also wonder what the offspring of current first-generation immigrants would do/make if they were able to traverse an art school. How much do you leave to the imagination of your audience if your audience is unconsciously racist? How can I be honest about my subjectivity (self-critical/human) without risking forms of toxic overidentification with aspects of my work (particularly in relation to the racial slurs and imagery), even if I am framing some of my work in a fictive or auto-biographical mode? In some respects, I’ve been wrestling with the tension affected by acts of unapologetic self-reclamation. How can I operate in a mode that isn’t solely defensive from the point of artistic departure? How do I subdue my own persecution complex? Should I subdue my own persecution complex? What is my persecution complex? It’s all about who sets the agenda and what their values are. It’s about identifying barriers, the immovable movers and the unspoken speakers. Considerate fictions help too.

Emilia Terracciano is Lecturer in Modern Art History at the University of Manchester. Her research interests lie in modern and contemporary art with a focus on the global south. Currently she is working on a monograph about art, nature and futurities in the global south.