Listen to the audio version of this essay on Soundcloud. (Listening time: 12 minutes)

“Editing for me is compulsive,” Maryam Tafakory explains, when I ask about her methodology — underlining viscerality in her urge to cut and layer, re-view and re-imagine. Her textual and filmic collages interweave archival and found footage, as well as poetry — in words and in form — a break acting both as split and bridge. Tafakory’s attentiveness to this duality carries echoes of the new wave of Iranian poetry, which came to the fore in the 1950s. It was revolutionary both in its simplicity and its possibility — poets, beginning with Nima Yushij, broke away from rigorous and long upheld notions of form and meter. This is not to say that free verse was simpler to write than coded structures: within this new found freedom, the placement of every word, the break in every line, became a matter of heightened meaning and responsibility. Taking on this mantle in the filmic space, Tafakory is masterful in deploying the weighty power of caesura. Whilst her earlier works often experimented with singling out senses, limbs, sounds, words repeated and embodied as visual chorus on screen; her recent work had delved increasingly into archive, re-viewed, re-ordered, re-told. Her already rich body of work becomes both split and bridge — a place to pause.

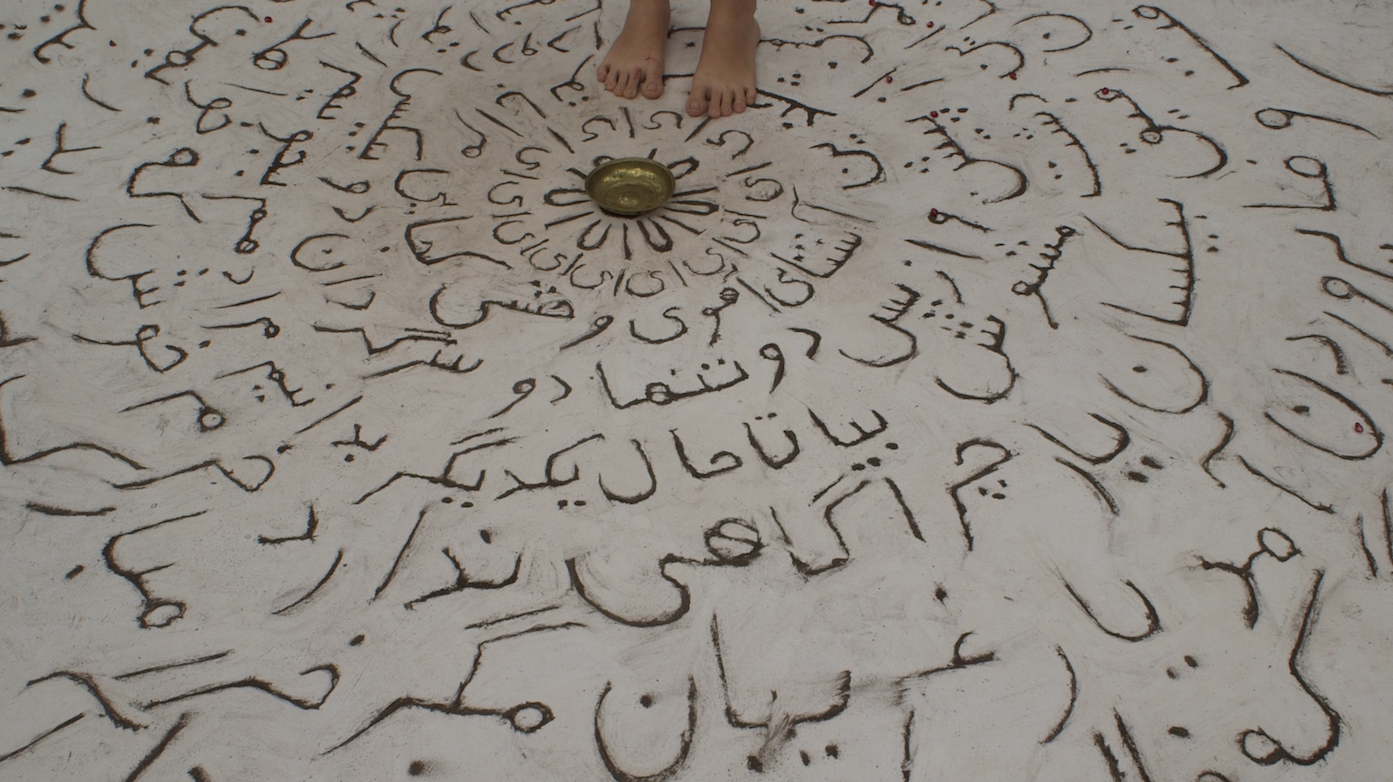

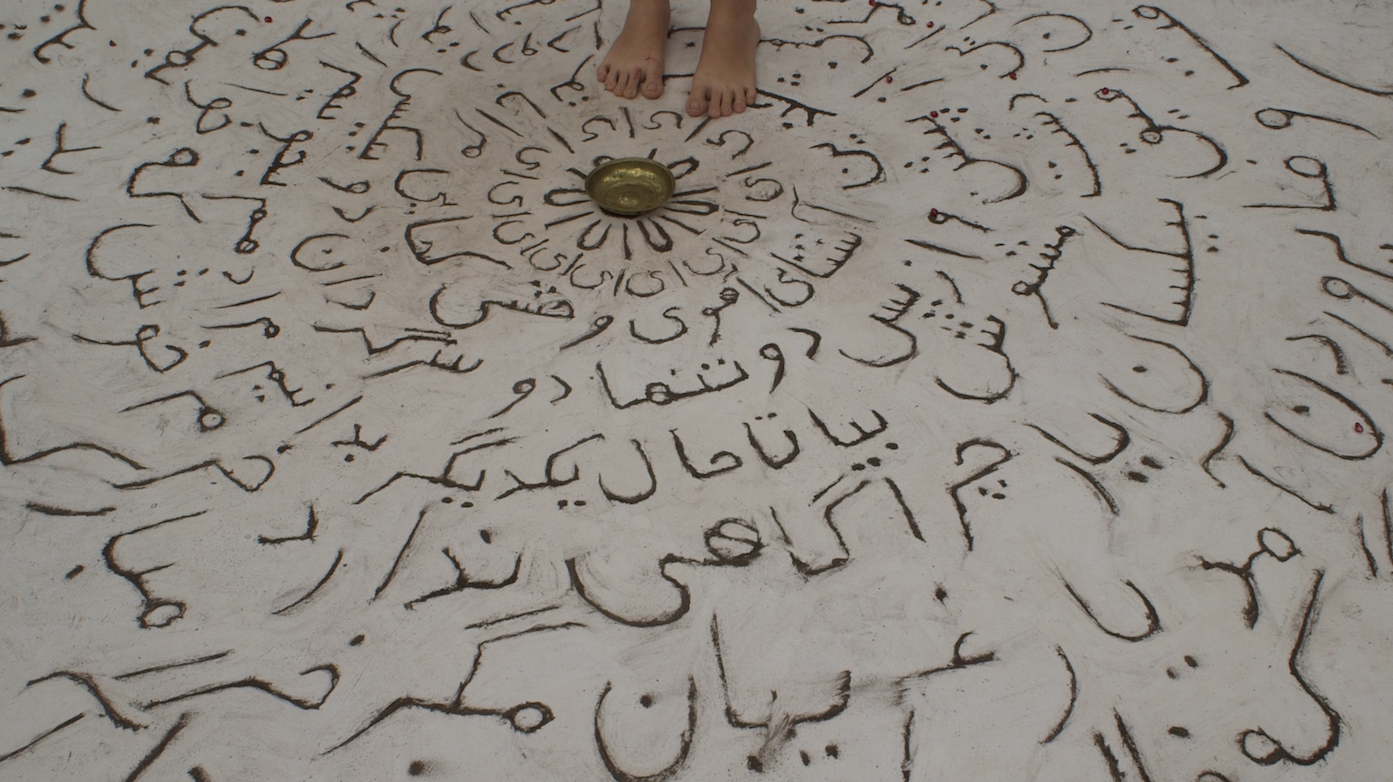

In Tafakory’s earliest work, Fragments (2014), disembodied hands hold, carry, rise, and fingers pointing to the sky. They purr in unison and form a dancing arch. We hear the striking of a match, the crackling of a flame. Farsi text on screen is translated into English, I dreamt you ate me. No audible voice addresses the unnamed ‘you’, yet the sense of speech prickles at the surface of the viewer’s skin. In Poem & Stone (2015), September in Tehran is brought to life through taste, touch, scent — boiling beetroot and steaming fava beans on the street corner, pomegranates frothing — ‘shouting’ — vats of freshly chopped sabzi, lavash bread stretched, ready to be thrown against the walls of a searing tanoor. Juxtaposed with the bustling city noise, the filmmaker’s feet stand vulnerably in a white frame. A fistful of earth dashes the white expanse; her fingers push the earth into carefully shaped mounds of circular words, filling the frame. The rigour and process in the construction of this imagery imbues the frame with multiple forms of kinetic energy, as if physical work aiming to displace something — a system, a definition, an idea, a space. Her hands drop pomegranate seeds into a brass dish. Fragments of text travel across the screen in Farsi and in English — sometimes translations, sometimes not; the journey of the soul involves not time and place. Her hands split a pomegranate, as if in offering. The film circles to a close with lines from Rumi’s Masnavi (book 3, story 12):

If you go home

bring me a handful of earth

Rituals re-interpreted — pulled apart and re-stitched.

Poem & Stone, Maryam Tafakory, 2015

Convention is further challenged in Absent Wound (2015), which takes place in a traditional wrestling space or “Zurkhaneh”, literally, ‘house of strength’. The Zurkhaneh is a space of ritual, a space that honours the strength of the body — the male body; women are prohibited from entering. In a diary recounting the filming, Tafakory reflected, however, “with experience, I have learnt that most limitations lie at the entrance and rarely inside.”[1]

Tafakory shot the film herself, in a Zurkhaneh as well as in a functioning men’s bath, where she filmed before 4 am to avoid the men coming to shower; her ‘transgression’ serves to honour the potency of a body that menstruates.

Water ushers us into the space, and invites us, through words almost hiding in the folds of the image — close, close er. Images of the damp, empty bathhouse and its dripping taps oscillate with those of wrestlers moving to the sound of frenetic drumming and occasional bells. Juxtaposed onto these images, are texts from religious guidance website, where people post their conundrums for the clergy to respond to. Fragments from Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex fade in and out. We see the filmmaker’s hands hover over lines of scripture. We see a trail of blood seep down her bare legs.

Among the many layers of invisible work burrowed in these frames is the ingenious use of dress Tafakory wears to shoot — her description gives some insight into the consideration and orchestration at play in every shot: “I am wearing an ankle length skirt that I designed and sewed for the scene in which I film myself menstruating inside the bathhouse. a thick black loose material, with two large pockets and a soft elastic waistline with which I can roll the skirt all the way up to expose my bare legs, and roll it down in a flash in case of emergencies.”[2]

On screen, a rush of water carries away impurities — blood is washed down the drain, a word lingering in frame alone is washed off the screen.

Absent Wound, Maryam Tafakory, 2015

Further building on feminist text, I Sinned a Rapturous Sin (2017) is a wry reflection on the policing of women’s bodies and sexual desire. A collage is built up around found footage of religious leaders advising on foods to eat or to avoid and to repress desire (an intriguing list, including dates, onions, garlic, fennel seeds…) — these are interspersed with scenes of a cotton carder, rejuvenating pillows and mattresses by beating their fibers, a moment of languorous lettuce eating as reflection of desire in Aroosak Farangi (Western Doll) by Farhad Saba (2005), as well as two women mockingly lip syncing the advice, loose chadors purposefully slipping off their heads. The film also pays homage to poet Forugh Farrokhzad — the title being a line from her first published — and endlessly controversial — poem “Sin”. Subsequent lines of the poem are scattered through the film — several repeated erratically as if a mantra, others taking shape on screen, as the filmmaker’s hands sketch Forugh’s words in white chalk onto a piece of black cloth. The closing sequence sees a group of schoolgirls dance joyfully in front of their classroom blackboard. This subversive found phone footage carries the foreshadow of schoolgirls we’ve more recently seen leading the anti-government revolution currently underway in Iran — audacious, unapologetic, firm in their knowledge and their power.

Tafakory’s two subsequent films look to subversion from another lens — delving into cinematic archive, a space she refers to as a “mirror of a specific history that is outside cinema. one that is defined by erasure, feigned truths, and forbidden bodies,” a site of state violence, in short, of “countless attempts to homogenize consciousness, to erase bodies, to conceal decades of atrocities”. She qualifies this ‘return’ as “not just a necessary and uneasy dialogue, but to remember not to forget”. Irani Bag (2021), made as part of the Asian Film Archive’s ‘Monographs’ series, reflects on bags as mediators of touch in the post revolution Iranian cinema. The bag is the limb exempt from the prohibition (on touching); sitting in between two people of different genders, the bag both separates and connects — like a line break, or an edit. Touch is what escapes the eyes — the frames between our blinks. Irani Bag also acts as a prelude to Nazarbazi (2022), a stunning collage film made at the height of the pandemic, reflecting on distance and its measures, the vulnerability of longing and the prohibition on touching on screen, woven together from some 87 films of post revolution Iranian cinema. “these films left their imprints on the psyche of my generation. they made me who I am, even if consciously I struggled to enjoy many of them,” Tafakory reflects. “revisiting this archive was not just an encounter with my teenage self, but also an encounter with the disconnection between how my mind processed these images versus how my body did”.

In reshaping them, Tafakory gives us space to pause, to reflect. “editing is my safe home,” she reflects ” it’s the sharing of it that is always disturbing”.

[1] Fragrant with Jasmine: An Unfinished Three Day Diary, by Maryam Tafakory, in Non-Fiction Journal issue 001, p 66.

[2] Fragrant with Jasmine: An Unfinished Three Day Diary, by Maryam Tafakory, in Non-Fiction Journal issue 001, p 68

Elhum Shakerifar is a BAFTA-nominated producer, curator, writer and translator working through London-based company Hakawati (‘storyteller’ in Arabic). Her credits include A Syrian Love Story (2015, Sean McAllister), ISLAND (2018, Steven Eastwood) and Even When I Fall (2017, Sky Neal & Dara McLarnon). Elhum was MENA/Iran programme advisor for London Film Festival for 7 years until 2021, and has curated for Shubbak, Barbican and Birds-Eye-View. She has taught documentary at Berlin Freie and UCL as well as on programmes from Georgia to Lebanon via Egypt and Tunisia. Elhum was recipient of a BFI Vision Award in 2016, she was awarded the Women in Film & TV BBC Factual Award in 2017. www.hakawati.co.uk