In the text accompanying their 2016 film Scriptures of the Wind Moojin Brothers ask us to “imagine the faces of the young people in this era” through their subjects; two brothers working arduously in a dystopian foundry. A question that keeps ricocheting from multifaceted issues they interrogate and coming back at us. Three short films presented at the London Korean Film Festival (from 30 Oct – 2 Nov) ground on the artists’ distinct experiences with the generational conflict, transnational capitalism and political upheaval in South Korea while the engendered parables are porous and ambivalent. In this interview Moojin Brothers talk us through their process of probing wounds of contemporary society and reflecting on their generation through drawing inconclusive portrayals. This interview was conducted by Sun Park through email and translated with support from the London Korean Film Festival.

You have been creating works telling stories based on emotions and doubts that are felt in various parts of Korean society. In the Coronavirus era, are there any changes in the way you are observing the world and communicating your works?

There have been a lot of changes. As there are restrictions on the physical aspects of work and life such as social distancing and the closure of the spaces, the online alternative is proportionately increasing, which is something that has been quite difficult to carry out smoothly.

Despite this, the video works are actively being shown more. But it seems that working online has given us a difficult task. Currently in Korea, for reasons such as identifying the COVID-19 positive patients early on and containing the spread of the virus, personal information (especially the route of travel) is thoroughly collected by the government, and there is actually considerable controversy over this issue. It seems that this problem of collecting personal data has become highly apparent since the start of COVID-19. The data of our body is already being collected by thermal imaging cameras and facial recognition in various places across Korea. We were even contacted by Korea’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention based on the record they collected of the exact date and time of a place we passed by in a car. The subject we have been interested in discussing since a few years ago has been the issues around the ‘big data’ era, and we have raised this issue through our recent work titled Orbital Squares (2020). What we were extremely concerned about has become a reality in this current situation. Placing ourselves between the unconditional acceptance and criticism of personal data collection, we are now contemplating about how we can expand on the reasons and the purpose for technology. Additionally, alongside producing videos, we carry out participatory public art projects once every two or three years. For the foreseeable future, public art projects in which many people work together in a space has become virtually impossible. As a result, we are postponing the public art project we had planned until next year and we are now researching to configure how we can carry out a participatory public art during this time.

In Scriptures of the Wind (2016), characters of two brothers appear as the protagonists who represent the young generation. Do you have any specific issues you had in mind that led you to create this work?

At the time of creating the work Scriptures of the Wind, there were many stories about the generational conflict in Korean society. The term ‘Hell-Joseon’ was popular among young people, as they were angry at the unfair customs they felt had been passed down from the older generation. Such anger was further provoked by the Sewol ferry disaster, which eventually led to the candlelight revolution. Being part of the younger generation at the time, we too were in a similar position. The reason why we chose stop motion for this work is because, oddly enough, we could not visualise the portraits of our contemporaries in our minds. When we thought of our father’s generation, we could only think of the situations and objects that they had created, and we could not identify or explain our contemporaries of the younger generation under a single identity. When we put together the characteristics of our generation, somehow the dynamics were lost and we were only left with words and images that were coined by other generations, and we seemed to be just floating between the online and the offline space without any solidarity for each other. As we collected and connected these passive movements and the timeline that always seemed disconnected from something, we came to think of a stop motion without a face. Of course, it is not the intention of this work to separate the older and the younger generations nor say what is right or wrong. We just wanted to raise the questions as the younger generation, as to where we stand in life and what part of life we contemplate on.

Scriptures of the Wind (풍경), Moojin Brothers, 2016. Courtesy of the artists.

I would like to ask a little bit more about the motivation behind using the phrase “stay still” as the core message in Scriptures of the Wind. The Sewol ferry disaster became even more devastating as a few irresponsible adults instructed the students to “stay still” at the critical time when they should have escaped from the sinking ferry.

In Korea, the phrase “stay still” has become a reminder of the Sewol ferry disaster. It was the most spoken phrase around the time of the disaster, and there was even a song made about this. However, these words are not limited to the Sewol ferry disaster. This single phrase contains all the abnormalities and submissive misery experienced by our generation. It is not just a command to be patient, but a command that must be followed without knowing why. On the 16th of April 2014, among the students on the Sewol ferry, only those who did not listen to these words and chose to escape survived, but the rest of the students adhered and stayed still after hearing those words from the adults.

After Scriptures of the Wind, you worked on the project The Trace of the Box for a while, which includes Now, Curiosity about the World (2018) and A Better World (2017). We are screening both of those films as part of this programme. What kind of project is this and what was the momentum behind it?

There were many momentums for the idea behind The Trace of the Box, but primarily it is a work that reads the present – which is about what makes us think now from the works of the past. Our future-orientated footprints, which are now taken over by big data, are also important, but somehow the blurry footprints that follow their own path without being easily embraced by big data were more noticeable to us. Among these include numerous works of art, language of the modern poets, the East Asian classics and the Buddhist thinking. For example, the inspiration behind Now, Curiosity about the World was Jules Verne’s submarine Nautilus from his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870). It is a fictional submarine operated by nuclear power – which did not exist at the time – and manufactured by multinational technology. In particular, the passage in the novel that indicates how the submarine is made by multiple nations completely overlaps with the manner in which the multinational companies that made Lotte Tower, which is the biggest building in Seoul, were cited. This sci-fi-like imagination that has now become a reality was interesting for us, and after looking at the Taegeuk Journal by students who translated it during the Japanese colonial period, we asked questions about the image of the future we are aiming for. At that point, we thought of the biggest building in Seoul that had recently opened – a place that is shaped very similarly to the Nautilus.

In Now, Curiosity about the World, the identity of the building is unknown as the images of the inside and the views of the outside from the inside are superimposed. It creates a world where you can’t see the reality as if you are trapped inside. Are there any reasons why you chose not to show the iconic appearance of Lotte Tower from the outside?

If you read Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, it is full of passages where Dr. Aronas looks at and describes the scenery and life under the sea inside the Nautilus. The description of the Nautilus‘ appearance is also important, but oddly enough, we were more intrigued by the way in which he observed the world from within the submarine. He observes the ecology of sea creatures in a very safe and comfortable environment within a huge submarine, protected by the thick glass in between. The way he looks at the world seemed very similar to the way we look at the world now. The Nautilus, which used to submerge into the sea, has now transformed into an observatory on a skyscraper with a huge aquarium inside itself, so that many things in the world can be observed without sailing or flying. It is with the desire to capture the landscape of the world with naked eyes by simply taking a lift to safely go up and down between the high-rise floor and the deep basement floor in a blink of an eye. The way in which we view from within the Lotte Tower is similar to the way we deal with this world we have built, as well as how we connect with all objects. In that respect, we thought that we would not necessarily need to show the exterior of the bizarre and huge 21st century Nautilus that we are using.

The Trace of the Box – Now, Curiosity About the World (궤적 – 목하, 세계진문), Moojin Brothers, 2018. Courtesy of the artists.

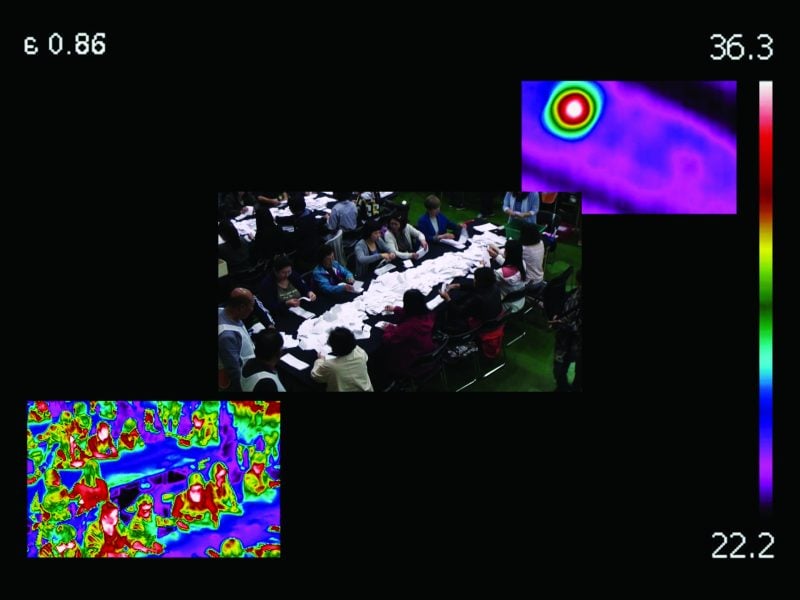

Let’s talk about A Better This film was shot during the presidential election in 2017, following the mass protests and impeachment of the then president. It was interesting to see how you filmed the vote counting station scene with a thermal imaging camera that is normally used to detect things that are not visible. Did you find anything interesting in the footage that you took with the thermal imaging camera as opposed to what you saw at the actual scene?

The world captured by the thermal imaging camera is very colourful. The boundaries are also unclear. At first, people counting the votes, ballot papers, and other objects each keep their respective colours and boundaries, but as people and objects start moving about frantically, the boundaries gradually blur and merge. Even cold ballots can turn red in the process of being passed along quickly between many people’s hands. As it was a snap election after the impeachment of the former president, the scene was filled with all kinds of surveillance, and the tension was higher than ever. Since the act of voting can change many things, the atmosphere of the scene itself turned out to be very fierce. We thought long and hard about how to express those passionate aspirations and how to capture the atmosphere of the count that happens overnight. To be honest, we thought directing would not be possible, let alone filming, so we thought at least we could capture the heat of the scene, and chose to shoot thermal images. In fact, when you watch the video in which the candidate’s name has been erased and only colours and shapes remain, you begin to think about what kind of world is contained within each voter’s voting paper regardless of victory or defeat. A normal video would have captured the tense atmosphere of the scene like a documentary, but the thermal images disperses all the tension and conflicting things and presents only colorful movements. Looking at this, we wanted to ask more about what kind of world each voter dreamed of and voted for (not what kind of candidate).

A little over three years have passed since the 19th presidential election. How has your political interest and enthusiasm changed since the turbulent times of the 2016-17?

Both sides are fighting fiercely, with one side trying to root out corruption and the other trying to win the next election. The conflict seems to continue. Meanwhile, the political voices in various other fields such as environment and labour are also rising. Apart from when the square was briefly cluttered on the 15th of August, the streets of Korea are seemingly quiet these days. Compared to last year’s protest of 1 million people in Gwanghwamun and the streets of Gangnam against the former Justice Minister Cho Kook, it is really quiet. However, there is a really fierce battle going on in the media and on the Internet. The fight for political power is fierce. Even the general election, which seemed impossible at this time, somehow went ahead successfully with people lining up and putting on plastic gloves (it is said that the plastic gloves discarded that day are about the height of the ‘63 SQUARE’ building in Seoul). The aftereffect of the unprecedented impeachment of the former president seems to be still ongoing.

There is much uncertainty about this Coronavirus era, but could you tell us about the work you are currently planning?

We are continuing with works that observe and document the current situation. Of course, the next one won’t be a work that captures the current situation exactly as it is, but we are looking for what we can bring out from the present. First of all, we are taking videos while walking around various places, and we are also conducting research by meeting with various kinds of people. Among the voices constantly crying out for the fourth Industrial Revolution, we are trying to capture this phenomenon in a video while watching them calmly from a distance. We have not yet specified how we will reveal the outcomes of our observations in the next work. The way we work – observing the situations around us and questioning it – will not change even during this Coronavirus era.

LKFF Artist Video Strand: Moojin Brothers is screening on the LUX website from 30 Oct to 2 Nov here

The festival runs from 29 Oct to 12 Nov – access the full programme here