“Jack and I think alike. I do glorious catastrophes, so does Jack.” – John Vaccaro

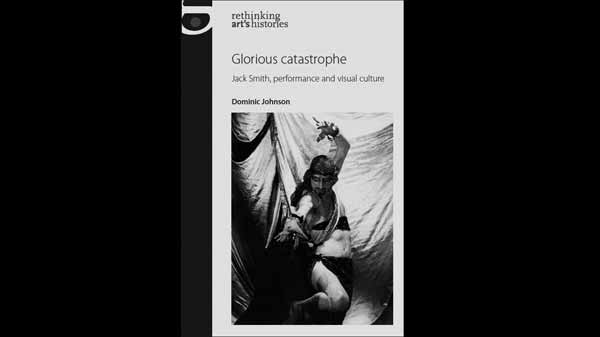

Jack Smith reclines resplendent in his plaster-strewn Atlantis, listening for the death rattle of an encircled tradition. Tilting his weary head, he sees enchantment in a luminous land. Smith was a central figure in the birth of the New American Cinema, and a founder of what came to be known as performance art. Moreover, he was an innovative photographer, a prolific writer, designer and draughtsman, a rogue interior decorator, and a vociferous critic of the art establishment. The first full-length study of Smith’s work, Glorious Catastrophe presents a detailed critical analysis of his work from the early 1960s until his AIDS-related death in 1989. In the book, I argue that Smith offers critical strategies for rethinking art’s histories after 1960. Heralded by peers as well as later generations of artists, Smith is an icon of the New York avant-garde. Nevertheless, he is often conspicuously absent from dominant histories of American culture in the 1960s, as well as from narratives of the impact that decade would have on coming years. Smith poses uncomfortable challenges to cultural criticism and historical analysis, which Glorious Catastrophe seeks to uncover.

Inspired by the 1960s subcultures of gay New York, experimental performance and underground film, Smith’s was a total vision populated by flaming creatures and pasty novelties. In his bejewelled retreat to the horrors of Orchid Lagoon, he spurned fame for the enigmatic pleasures of infamy, and kept himself elaborately busy in the company of imagined lobsters, penguins, clowns and cobra women. In his performances and polemics he longed for lost and imagined utopias, including the esoteric myth of Atlantis, and the gaudy, ‘gilded’ visual worlds of 1940s Hollywood. Smith relied upon the committed work of continual self-reinvention, and presented calculated performances of self, for audiences who were by turns bemused and transfixed by his variant imagination. Smith’s exercises in violated, transfigured identity were initially attempted through appearances in other artists’ works in the late 1950s and, soon after, his own explorations into filmmaking. This project of imaginative self-invention found its most effective manifestations in his epic live performances. These were arduous revelries in the ceremonial splendours of failure, degradation and humiliation, and Smith presented them in makeshift spaces, including his own adapted lofts, from the mid-1960s until shortly before his death in 1989.

Through his fantastical assaults on received wisdoms, Smith enables a political account of cultural marginalisation – its troubles and its effects. His emphasis on failure, excess and collapse conspire to muddy any attempt to neatly historicise his activities. He commands a new historiography of performance and visual culture: specifically, one that is sympathetic to his obstinate refusal to fit the existing historical, theoretical and formal accounts that seek to make sense of twentieth-century experimental culture. Smith’s practice encompassed both a camp affection for the refuse of contemporary culture, as well as a painful engagement with those experiences, objects, desires and practices that daily life commits beyond its borders. As Ken Jacobs noted, Smith’s attraction to failure was conditioned by his ‘horror of life, a deep disgust with existence. Jack indulged in it spitefully, he would plunge himself into the garbage of life [with] a hilarious and horrifying willingness to “revel in the dumps”.’ Smith’s artistic practice sits in a continuum with the excesses of his personal life – his class anxieties, his bohemian impoverishment, his ‘flaming’ queerness, his rage, and his near-maniacal propensity towards paranoia. As such, the fruits of Smith’s ‘moldy’ labours exceed traditional understandings of art’s work. Smith demands that another cultural history be written, in counterpoint to the dominant stories that condition our understanding of the 1960s and its aftermaths.

Smith achieved subcultural notoriety in 1963 as a result of the outrage caused by film Flaming Creatures (1962-63), which David Ehrenstein has called ‘the most important avant-garde film ever made in America’. Filmed on the roof of the Windsor Theatre over eight consecutive weekends, Flaming Creatures presents a gang of performers who fondle, seduce and assault each other in tableaux vivants and jostling dances. Inspired by the ornate composition of bodies in his early photographic works, the vignettes in the film are by turns languidly seductive and elegantly depraved. Smith’s ramshackle cast included artists of his circle, a heady mix of local personalities, beatniks, layabouts and queens, and a cluster of strangers plucked from the street. After its controversial reception, and subsequent banning, those in the experimental scene on the Lower East Side viewed Smith with a mixture of awe and trepidation. His notoriety was lent legitimacy by New York’s intelligentsia, most prominently Susan Sontag, and by Jonas Mekas’s persistent championing in the pages of his journal Film Culture.

Suddenly notorious for his oppositional art practice, yet forever struggling to keep himself afloat financially (and, perhaps, emotionally), Smith actively politicised his own marginal position. Of his own formal and political achievements, he writes, ‘They aren’t noticed because everybody’s minds are busily occupied by discussing how unrespectable I am, and other tempestuous brassiere curiosities like me. Well, it isn’t my flimsy costume, only, that gives me a chill at the underground night of the film vaults of artcrust.’ To endure Smith’s aggression is to attend to his protestations, however arcane, wide of the mark, or hysterical they appear. This critical orientation performs instances when the body returns with a vengeance, in the spaces where it has, as yet, only tentatively breached the skin of discourse. This enables me to pursue Smith’s works – especially his practices between performance and visual culture – guided by his own politicised responses to what he understood as a perpetual state of exploitation, misrepresentation and abuse.

Bearing in mind the fervour of his curious pleasures, and the potency with which they shine through in his art works, it may well be counterintuitive to expect Smith to figure unproblematically in histories of postwar art. Not simply a maker of challenging work, Smith was also a notoriously difficult personality, as attested to in countless memories of his impediments to the efforts of critics and historians; in one such anecdote, the film writer Sheldon Renan remembered in 1968 that Smith ‘agreed to an interview but replied to all my questions with his whole face pressed tightly against a pillow’, which perhaps influenced Renan’s description of as definitively Smith ‘beyond categories’ in his book The Underground Film of the same year. (He does appear under a category later in the book, namely ‘Madness’).

His performances were similarly diffuse and expansive. It is difficult to discuss specific performances by Smith, as the content and titles were used more or less interchangeably over the decades, and no full-length documents were made on film or video. His works had titles that signalled the ‘delirious hokey’ they celebrated, such as Wait for me at the Bottom of the Pool (1968), Brassieres of Atlantis (1969), Technicolor Sunset Easter Pageant (1970), Withdrawal from Orchid Lagoon (1970), Sacred Landlordism of Lucky Paradise (1973), or The Secret of Rented Island (1976). These performances were scripted to varying degrees, but inadequately advertised, documented, or reviewed. When he did publicise his performances, he placed adverts in unlikely places – the religious classifieds of freebie bulletins, for example – and provided abstruse content, to deliberately limit his target market and preserve his cryptic marginality. In terms of strategies for documentation, shorter reels of video and film footage were made of some performances, as were audio recordings; scattered photographs are extant; and some preliminary sketches or scripts survive in his estate. However, he clearly has a curious relationship to archiving his practice. Disrupting the normative desire to promote his career, or to make the past last, his non-durable works of art defy the promise of immortality afforded to individuals proved worthy of ‘making history’.

Glorious Catastrophe zones in on the borders between the mainstream and its outsides, veering suggestively outwards to marginal, minor, peripheral, emergent or oppositional spaces of culture. As should become clear for readers of the book, I do not seek to recuperate Smith into a reconstructed canon. Instead, I consider and in some ways privilege the off-kilter placement of Smith between (and to some extent outside) the distinct and often incompatible histories of performance and visual culture. Smith is apposite in this respect, as he both predates and endures the acknowledgement of performance art as a valid artistic category for formal, institutional, and academic consideration, from the late 1960s onwards. Smith is ideal for a ‘minor’ history of performance and visual culture. As it were, Smith interrupts those histories written in a major key.

Dominic Johnson is a Lecturer in the Department of Drama at Queen Mary, University of London.