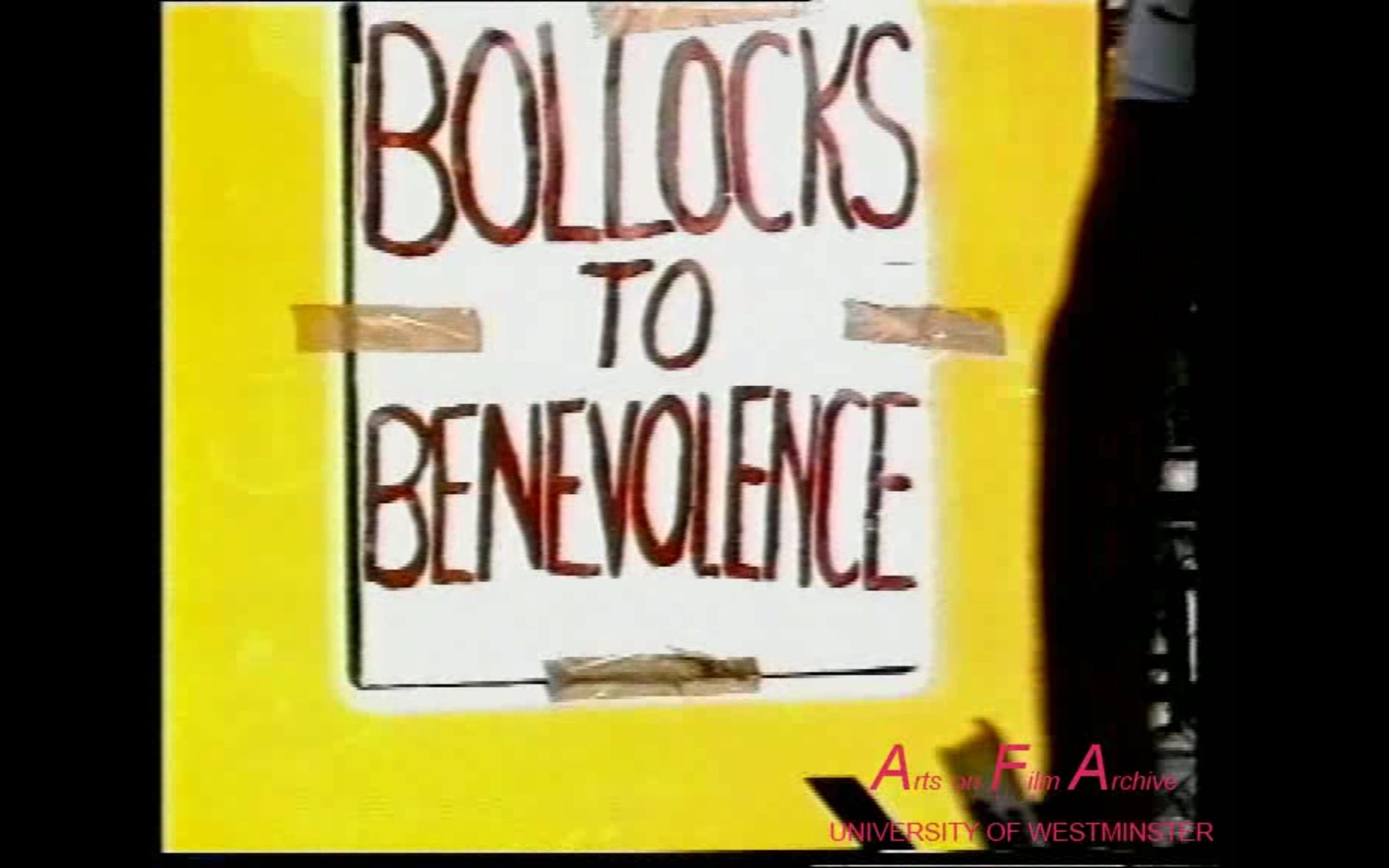

Most filmographies are works in progress, or fuzzy around the edges, and the one at the end of DWOSKINO is no exception. There are remaining mysteries even to do with the finished films, let alone the unfinished ones, and one or two missing titles that might have been included under ‘collaborations’ – namely The Shaping of DAM (1995), to which Dwoskin contributed footage of a protest held by disability rights activists against ITV’s charity Telethons, in a spirit best captured by the placard ‘Bollocks to Benevolence’.

Previously called Disability Arts Magazine, DAM was Dwoskin’s main outlet for writing in the early 1990s, and he was a friend and adviser to its founder and editor Roland Humphrey, who directed the film at the end of his tenure, in part to explain his departure. His reasons are given more clearly in an accompanying booklet of the same name, in which Humphrey defends his ambition to produce an aesthetically pleasing magazine that didn’t lower its artistic standards for political reasons.

Dwoskin had made his final contribution the previous year, in early 1994, with an article that makes similar arguments. The last paragraph of ‘Notes from Somewhere’ is about the difficulty of artists achieving autonomy, which he compares with ‘the lack of autonomy given to people with disabilities’. Artists, he writes, have become ‘dependent on institutional support’, and his slightly cryptic last words are: ‘Wonder if all this is disability culture or just culture.’

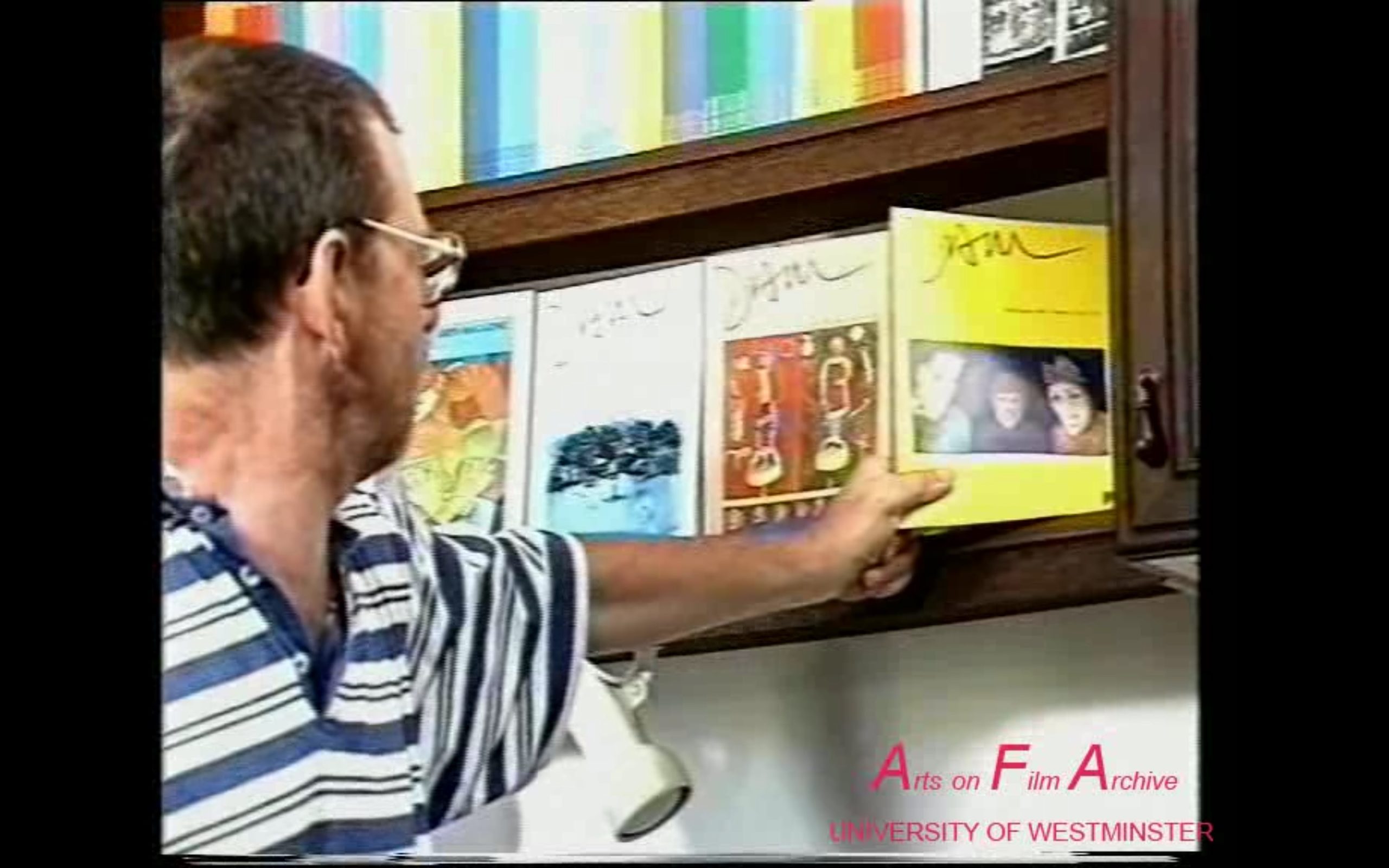

Roland Humphrey in The Shaping of DAM

Like Dwoskin at this time, Humphrey was dependent on the Arts Council and similar organizations, and the most effective part of the film is a point-of-view sequence of a wheelchair user trying to navigate a dilapidated railway station, while a statement of the Arts Council’s high-minded purposes is intoned in voiceover narration. DAM’s annual budget was then £30,000, and Humphrey, based in Grimsby, did not feel well supported.

Dwoskin had been in most of the issues Humphrey had edited, starting in 1991, while Dwoskin was preparing Face of Our Fear (1992), with an article titled ‘Media Apartheid’, on the long history of stigmatizing representations of the disabled in western culture, from the Bible onwards – material that would go into the film.

About the time of the film’s broadcast, in spring 1992, as part of a Channel 4 season, ‘Disabling World’, Dwoskin contributed an article that criticized his patron on a number of fronts, including the decision to run the film as part of a season in this way. ‘Personally, I am against this tokenistic presentation of work about and by disabled people in this way – an isolated and labelled way. It can easily run the risk of reinforcing the marginality of the subject.’ He also attacked the licence-holders of films depicting the disabled who had refused him permission to extract their work, including the owners of My Left Foot (1989), a film Channel 4 had included in the season.

Later in 1992 he levelled similar criticisms against the first Festival Europeo Cinema Handicap, held in Turin, the most disturbing aspect of which was ‘the fact that most of the films were made by non-disabled people about disabled people’.

Dwoskin’s contributions were not all negative – he wrote articles in praise of Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun (1971) and Yilmaz Arslan’s Langer Gang (1992). But as was not infrequently the case, he found himself trapped between the commercial mainstream, which promoted conventional body images – as he argued in ‘A Degenerate Art Lesson’, which drew parallels between Nazi and non-Nazi approaches to representations of the body – and ‘the bureaucrats collecting the handshakes’ in the subsidized sector.

One of Dwoskin’s promotional images for DAM

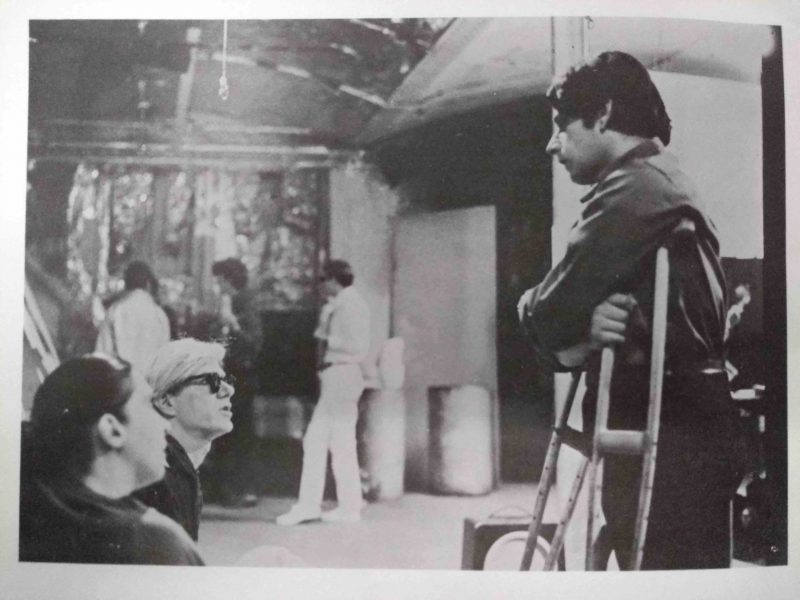

Published at the end of 1993, ‘A Pleasure of Difference’, Dwoskin’s penultimate contribution to DAM, published as he began work on Trying to Kiss the Moon (1994), is one of the most revealing articles he ever wrote about his own films, though it is nominally about what he sees as positive representations in the work of others: Bergman, Warhol, and Jack Smith, all formative influences on Dwoskin in his early career – though ordinarily he would disclaim the influence of Warhol.

Whereas ‘A Degenerate Art Lesson’, published in the previous issue, had characterized mainstream entertainment media as providing ‘a steady diet of morality and idealized, mythological beauty’, ‘A Pleasure of Difference’ argued that only the avant-garde or art cinema provided an alternative. It may begin with the same ‘contemplation of the body as the mainstream, but explores and uses the image of the human form as a vehicle for demystification and dissection’ and ‘reorders perceptions and expectations’. In Bergman, ‘the dissection of the image occurs through prolonged studies of facial expression’ – clearly the starting point for Dwoskin’s own films, such as Moment (1970), which he defends in the same article.

Dwoskin was profoundly ambivalent about being identified as a disabled artist, but genuinely committed to the magazine – and to Humphrey. Most of the surviving correspondence between Dwoskin and Humphrey postdates Dwoskin’s written contributions. He continued to provide advice on layout, and designed promotional materials, as well as helping with the film, which was made available on video at the time, and is now available to some through the University of Westminster. Later, the pair of them won development funding for a film about MS, based on Humphrey’s experience, Something Evil This Way Comes; but as so often that story will have to wait for another occasion.

XXX

Henry K. Miller is a senior research fellow at the University of Reading, author of The First True Hitchcock, editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat, and co-editor of DWOSKINO – available now from the LUX shop.