Outside In begins with a personal introduction from Stephen Dwoskin, standing in front of a cinema screen – the Gate in Notting Hill, in fact – his arm round an unnamed female ‘friend’ whom he obnoxiously won’t name, and who can’t find words of her own. The film, he says, is about his life, transmuted into fantasy, and so it is; but he knew by the time he made the film in 1981 that these fantasies would meet feminist objections, and the introduction must have been designed to ratchet these up a notch. The simpering friend is in fact the Italian actress Olimpia Carlisi, who would appear in the same year in Bertolucci’s Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man, and there is no sign he had met her before her brief trip to London in March 1981. In his autofictional films, Dwoskin was determined not to show himself in his best light

A few weeks after shooting his scenes with Carlisi, on 10 April, Dwoskin wrote to Eckart Stein, the producer who had commissioned the film for ZDF, in Mainz, ‘to tell you the state of the film (which I am now calling “Outside In”) and that there will be a delay in the date of completion’. His main reason was a botched operation on his foot the previous December, which had led him to ‘going in and out of the hospital’. As of mid-February, according to his diary, he had thought it ‘impossible to even think about doing the Z.D.F. film much less “work” on the film’, between the foot and the day job teaching, among other burdens and responsibilities – and, as his diary records, the era’s high inflation, which shrunk the budget day by day. His foot was causing him pain throughout Carlisi’s time in London.

Dwoskin and Merdelle Jordine

Apart from that, because the film had failed to win co-production funding, it was being done on a shoestring, relying on the availability of friends, who made up the crew, and so had to be shot in short bursts. There was still, then, the hope of a completion grant from the BFI’s new production head Peter Sainsbury, but this never materialized; nor would he ever again feel the BFI’s warm embrace, as things turned out. A small sum came from a fund associated with the Rotterdam film festival. In his April letter Dwoskin proposed to finish by June – if the film was to mark the International Year of Disabled Persons, it would need to be turned around fast, but this was unrealistic in the extreme. It is a reflection of the enlightened spirit of ZDF, and Eckart Stein, that the production was allowed essentially to take as long as it took.

As is typical with Dwoskin’s diaries, it is never that easy to discover what he spent his time doing: they mostly record his emotional state, and when work comes up, the recurring theme is his frustration at his lack of progress. Outside In came together gradually. What seems to have been the first footage was shot by James Scott, another British-based ‘ZDF filmmaker’, and a colleague of Dwoskin’s from The Other Cinema, in Rotterdam, in February 1981; Scott himself is unsure whether it went into the finished film. After the Olimpia Carlisi scenes in March there are no easily identifiable shooting days until late May, when Dwoskin filmed with Ilona Jeismann, a German journalist he had met in West Berlin in 1974, who is shown trying on his crutches and callipers.

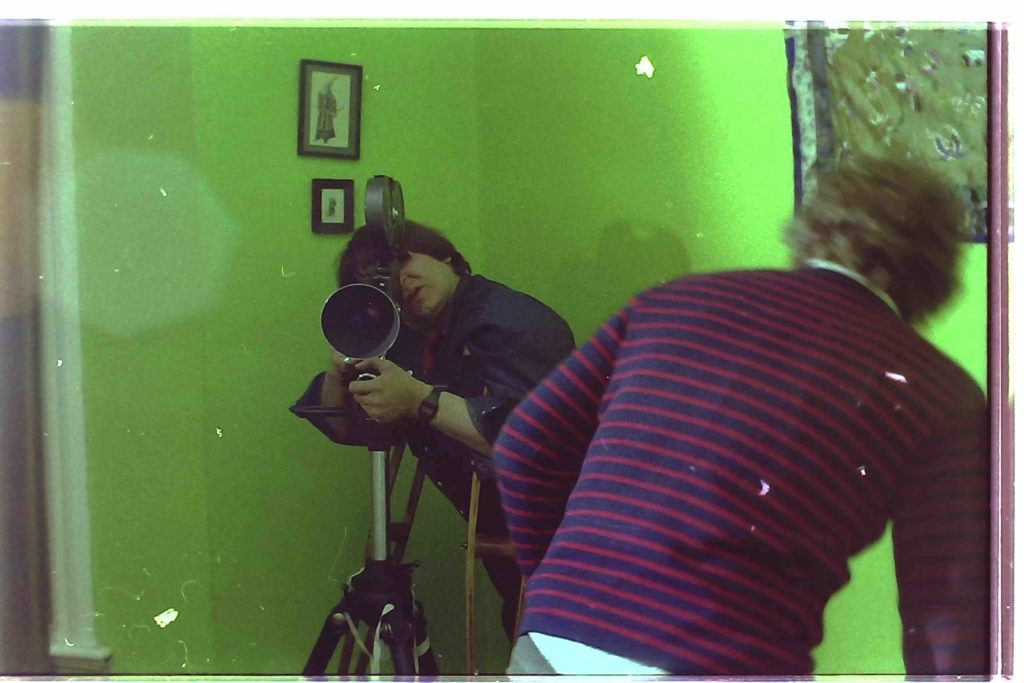

Dwoskin behind the camera

A significant proportion of the cast flew in for their scenes, not only Carlisi and Jeismann, but Edith Kramer, a film curator based in San Francisco, Marie Manet, a French actress Dwoskin only met for the first time in May 1981, and Beatrice ‘Trixie’ Cordua, Dwoskin’s long-term collaborator. July and August 1981 are the blankest months in the diary, and the busiest months of production, but he was still filming, and his foot was still in pain, in September. ZDF and Stein continued to show forbearance, extending the deadline to November. As of 25 October he claimed to have ‘no editor’; soon he found one, Anthea Kennedy, a former RCA student, though not part of Dwoskin’s clique, and herself a filmmaker. The diary does not disclose when Outside In was finished, but they were still working on 22 November, and it was broadcast in West Germany on 10 December – work continued afterwards to produce a ‘married’ print, shown at Rotterdam in the New Year.

Dwoskin’s home editing rig, as seen in Outside In

The result is the first of Dwoskin’s films that could be called entertaining, or which might have had a realistic chance of commercial success. It won critical plaudits in France in particular. The year was full of foreboding for the death of cinema, caught on film in Wim Wenders talking-head film Chambre 666 a series of interviews with directors shot at the Cannes film festival, and seemingly symbolized by the death of one of them, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, a few weeks later. Louis Skorecki, reviewing Outside In in the July–August 1982 Cahiers du cinéma, wrote that ‘I want to announce – yes, as good news, a last-minute surprise – is that the death of cinema is temporarily postponed, and that there is still a filmmaker.’

There may have been a filmmaker, but the central problem of Dwoskin’s career remained intractable. When he arrived in London in 1964, there was nowhere to show his kind of film; he and others had had to create a space for them, initially the London Film-Makers’ Co-op. That enterprise had continued in the 1970s, most notably with The Other Cinema, which aimed to carve out the territory ‘left’ of art cinema, which included Dwoskin’s films, but had not managed to survive independently, nor attract state funding, surviving as a distributor. Outside In had its main run at the ICA as part of a Dwoskin retrospective in September 1982, but it never had wide distribution. Channel 4 had sought to buy it even in October 1981, before it was completed and before Channel 4 was on air, and it must have had its biggest British audience when shown on the new station in 1984.

There hovered and perhaps still hovers over Dwoskin the sense of never emerging far enough from his underground roots to reach the art cinema heights; or of falling between two stools, appropriately for a film with a lot of falls. Seen without reference to these historically contingent modes of distribution and exhibition, however – and it was made without reference to either of them – Outside In is a triumph. At the end of the film Dwoskin again addresses the viewer directly, this time telling us that he and his collaborators were not interested in criticism, and had ‘read every book, feminist, Marxist, leftist, rightist, uppist, downist, greenist, blackist – we are concerned with the quality of motion picture and nothing else’. As with the introduction, the wind-up is wholly sincere.

We are immensely pleased to say that writer and disability arts activist Allan Sutherland will introduce a screening of a new 2K scan of Outside In at BFI Southbank on Monday 7 February.

XXX

The Dwoskin Project is based at the University of Reading and supported by the AHRC. Visit its website: https://research.reading.ac.uk/stephen-dwoskin/

The Dwoskin season runs at the BFI throughout February. DWOSKINO: the gaze of Stephen Dwoskin is available now from the LUX.

Henry K. Miller is a senior research fellow at the University of Reading, author of The First True Hitchcock, editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat, and co-editor of DWOSKINO.