Dwoskin’s Face of Our Fear, which we are showing as part of a live discussion event on Friday 5 March, debuted in 1992 as part of a Channel 4 season, Disabling World. As the publicity pointed out, Channel 4, marking its tenth anniversary that year, had “established a strong, firm commitment to minorities”, and Disabling World would “extend and enhance Channel 4’s commitment to Britain’s largest minority”. Dwoskin, introduced in the same document as “a wheelchair user and a film director”, in that order, had the 9.30pm slot on the opening night, 22 March 1992 – giving him a prominence and a kind of responsibility that were rare in his career. But while he took this responsibility seriously, Face of Our Fear is in some respects a palimpsest, written over an earlier project.

As I have written elsewhere, some of its roots lay in a pioneering National Film Theatre season that Dwoskin had programmed with Allan T. Sutherland, Carry On Cripple, in 1981. It was in an interview with Sutherland, long afterwards, that Dwoskin revealed that Face of Our Fear came about when another project was rejected, in the autumn of 1988. In his recollection, “I was just getting so angry at the reasons they were giving, why they shouldn’t do this, shouldn’t do that, you know”, that the commissioning editor told him: “what you just told me, you should make a film about.”

Schedule for Disabling World

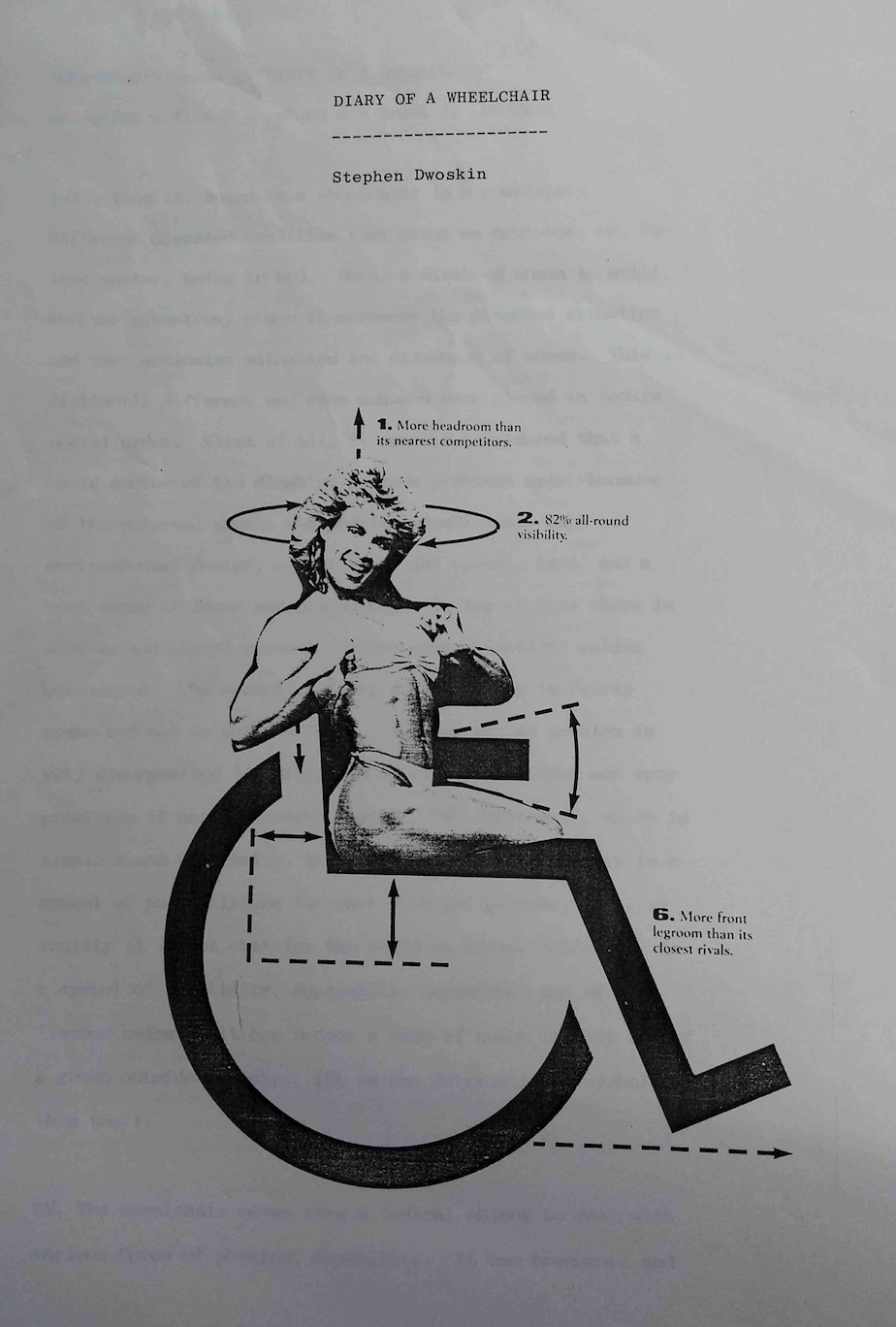

The rejected project was called Diary of a Wheelchair, and the commissioning editor at Channel 4 was Alan Fountain. ZDF, the German broadcaster that had backed three previous Dwoskin features had also said no. Dwoskin saw Diary of a Wheelchair as the next step on from his last ZDF film, Outside In (1981), a comedy in which he had played himself, a disabled man among the able-bodied. Sometimes it was titled Diary of a Wheelchair Woman, and alternative titles included A Disabled Woman’s Moment, The Day and Life of a Disabled Woman, and Mary Superwoman; unlike Outside In, the protagonist would be a woman. As in the earlier film, its focus would have been “social/sexual relations” rather than questions of mobility and accessibility, and the style would have been anti-realist.

In one version of the plot, the wheelchair woman would go into the world of the able-bodied, having come to know it only through books and magazines, and follow what she had learned from them, going after “a man, a baby, a job, and to take a ‘holiday’ at one of those resorts”. Coming from a world in which the physical environment is tailored to the disabled, she would be confronted with its opposite. “The film”, he wrote in one pitch document, “would have to become bold, strange, and, at times, even aggressive, but most of all follow the disciplines ordained by Surrealism.” Dwoskin’s most recent film at the time was Further and Particular, probably his most overtly Surrealistic film. The protagonist of Diary of a Wheelchair would “be a Wonder-woman”, sometimes massive and strong, other times dainty and doll-like, but still disabled’.

Cover for Dwoskin’s Diary of a Wheelchair proposal

Dwoskin explained that “by taking a woman I can more honestly explore the woman’s position freshly”, having put himself at the centre of two previous films. But the choice was also explained by his desire “to become more emphatic about the physical identity problem both able-bodied and disabled have about ‘looks’. It is about the social acceptance and value judgements determined by each other based on looks.” And for women in particular, “this stereotyped burden is added to the already difficult burden of the physical handicap; a double disability, which is both different and beyond that which men face”. The lead actress would ‘likely’ have had to have been able-bodied; as wonder-woman, she might carry her wheelchair up a flight of stairs. In fact, Dwoskin had in mind a female body-builder, partly to “alter the iconography most often used and associated with such a subject”.

It was turned down in the same instant that Dwoskin’s planned film about Marina Tsvetaeva was turned down; Fountain had qualms about its “sexual politics”, though without access to the archive during lockdown more cannot be said. Six months later, in May 1989, he gave Dwoskin a development deal for what was then titled Towards a Visual Essay on Disability, and the results – a great mass of word-processed documents – contain much of what went into Face of Our Fear, including its voiceover narration. Unstructured and difficult to categorize, the ‘Essay’ itself, dated December 1989, is a mixture of reflections, arguments, gleanings from Dwoskin’s research, and autobiography. Early on it discusses

that woman, who was paraplegic, who posed almost nude for the centrefold in Playboy magazine. Ellen Stohl was her name. She was tired of people seeing her as a cripple, so she took her clothes off and her wheelchair off, and what do you think – she looked just like a woman. When she was wearing the wheelchair, most people saw her the way they see most people in wheelchairs; as if their only gender were the wheelchair. It is the same for me; a sexless wheelchair.

Ellen Stohl may have helped inspire his proposal for Diary of a Wheelchair, and she would appear in Face of Our Fear, both “as herself”, and in a number of skits that are reminiscent of Dwoskin’s plans for Diary of a Wheelchair – comic scenes, including one where she, from her wheelchair, treats an able-bodied man as if he were the “abnormal” one. It must be admitted that these scenes don’t entirely come off; in this specific instance because the scene seems improvised, though Stohl herself, a trained actress, is up to the task.

Julie Umerle on the set of Face of Our Fear

“None of the cast had much of an idea of what would happen (not sure he knew either to be honest),” recalls Julie Umerle, another performer in the film. “The opening sequence where I am applying lipstick in front of a mirror seemed to come from nowhere. Something I was just doing and Steve thought it was a good idea to film.” In this more successful scene, and in others, Dwoskin brought into this flagship television programme traces of his underground roots. In her memoir Art, Life and Everything, Umerle recalls “one or two moments of scrutiny during filming that made me a little uncomfortable: a close-up in the opening sequence and individual portraits of each cast member later in the film where Steve aimed a hand-held camera in our direction and we just stared silently back, returning his gaze.”

These portrait shots, obviously reminiscent of his early films, begin under Dwoskin’s commentary on the opening soliloquy in Richard III, which he says “effectively illustrates what society thinks of cripples – in the disguise of the cripple’s own thoughts about himself”. As in the earlier films – with the difference that all of his subjects in those films were able-bodied – the confrontation with the camera, the meeting of gazes, is intended to be revealing, on both sides, so intended to be uncomfortable; intended to do away with disguises. In that light, Dwoskin’s decision to remove almost all traces of himself from the film – the chunks of autobiography that he included in Towards a Visual Essay on Disability – is quite striking. Possibly he already had in mind his next film, the autobiographical compilation Trying to Kiss the Moon (1994).

XXX

The Dwoskin Project is based at the University of Reading and supported by the AHRC. Visit its website: https://research.reading.ac.uk/stephen-dwoskin/

Henry K. Miller is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Reading, and author of the forthcoming The First True Hitchcock.