This post was to have been about an event which has had to be postponed indefinitely because of the coronavirus pandemic. Film School Portrait, which was to have taken place on 26 March, would have been a kind of portrait of the institution where Dwoskin was based during some of his most productive years, the Royal College of Art. One aim of the event was to bring together some of Dwoskin’s students of the 1970s, including some of those who worked on his films, and to show some of the films they themselves made during that decade. Tai Shani, a current lecturer there, was to have introduced a film of Dwoskin’s, and the event was to have ended with a performative film by Philomène Hoël, a recent graduate of the Royal College, and current PhD candidate at the University of Reading.

Dwoskin joined the staff of the Film and Television School some time in late 1972 or early 1973, his year of three features, when he shot (though did not complete) Central Bazaar, made Tod und Teufel, and began Behindert. Showing fragments of a relationship, as experienced by a disabled man, in London and Munich, part of Behindert was shot at the RCA, and its crew included RCA students Roger Ollerhead, Thaddeus O’Sullivan, and Mike Henley, as well as his teaching colleagues Peter Gidal and Val Drumm. It was the first of Dwoskin’s films to show him on screen, visibly disabled, but it did not tell his story; in fact he had reservations about it being treated as a ‘film about disability’, though that tended to be how it was presented, especially when revived in later decades.

The RCA, as seen in Behindert

Dwoskin told that story directly in unpublished writings and recordings. For a subsequent film, Outside In (1981), which he described as ‘the visual impression left during his process of integration into the so-called able-bodied society over twenty-years of adulthood, transformed into visual memories’, he recorded himself being interviewed about his life by friends. On these tapes he recounts the circumstances in which he contracted polio, aged nine, in 1948. Polio outbreaks were a fact of life in those years. In Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, Portnoy sees winter as the time ‘when the polio germs are hibernating and I can bank upon surviving outside of an iron lung until the end of the school year’.

Dwoskin’s aunt used to rent a cottage in Mountain Dale, a small town in upstate New York, during the summer months, and he ‘picked up polio there, in one of the waterholes in the mountains’. In this he was particularly unlucky. The narrator of Roth’s final novel, Nemesis, which is substantially concerned with a polio outbreak in Newark, New Jersey in 1944, writes that ‘escaping the city’s heat entirely and being sent off to a summer camp in the mountains or the countryside was considered a child’s best protection against catching polio’.

As Dwoskin recalled to Bobby Gill, who had co-written The Silent Cry (1977) with him, it was discovered about a week after his return to New York City, in the first week of September. ‘We were having a Chinese lunch, it was Saturday, we went shopping, in Jamaica N.Y.’, near the family home in Brooklyn. ‘I remember my legs hurting. They felt very stiff. It feels like flu, and that night I was throwing up, all those things like a violent case of flu. That was a reason why a lot of people did die, cos Drs waited to see if it was flu or polio.’ His didn’t: ‘he immediately got me into his car, and took me to the hospital..he carried me in and..they wouldn’t let me walk.’ Any movement would have spread the virus within him. He was kept in isolation for three months, and at one point, by his account, was presumed dead. ‘When I finally left the hospital I was 15, 16, 6 years later.’

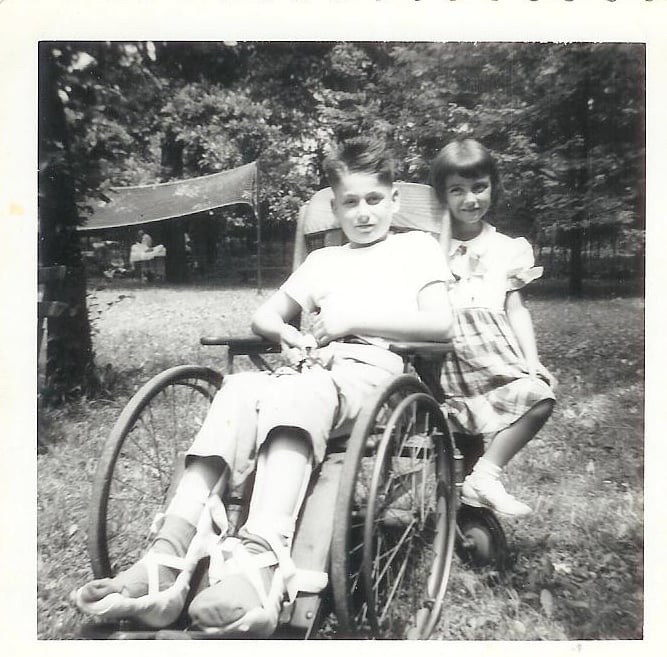

Dwoskin with his sister, Mary, at New York State Rehabilitation Hospital, West Haverstraw, 1949

In these interviews Dwoskin discusses not only the physical disability he endured, and the psychological effect of his reduced mobility, but also the psychological effect of his confinement in institutions during those formative years, surrounded by men, notably veterans of the Korean war, and physically separated from his family – the hospital, in West Haverstraw, was forty miles from Brooklyn. He also discusses his release from it. ‘I was TALL. I had GROWN all those years.’ He was not prepared for life outside – apart from anything else, he had undergone puberty while inside.

‘The thing I noticed most was loneliness. Suddenly without people to talk to.’ He ‘used to spend a lot of time looking out of the window watching people walking. Of course it was also the time when I was interested in girls.’ He spent a lot of his time in hospital drawing, and continued at home. ‘Probably drew out my fantasies..about women and girls.’ Dwoskin was consciously inventing the origins of his films in saying this, and no-one should expect the whole truth of a person from their own utterances. Dwoskin was raised in a particular culture like anybody else; a similar one to the one Roth knew. But it cannot be doubted that contracting polio divided his life in two. Dwoskin emerged from the hospital about the time a vaccine became widely available, developed by a team led by Jonas Salk. Godspeed those who follow him today.

The Dwoskin Project is based at the University of Reading and supported by the AHRC. Visit its website: https://research.reading.ac.uk/stephen-dwoskin/

Henry K. Miller is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Reading, and editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat.