Over the last 10 years or so much work has been done to research, preserve and screen UK experimental and ‘independent’ film and video made between the late sixties and the early-eighties.

It is during this time that much of the terminology used to describe film and video that strayed far from mainstream cinema and television were coined and in some cases contested. The terms – alternative, experimental, oppositional, activist and avant-garde etc – were as fluid as they were contentious. Also constantly changing were the sites of presentation for this work. It was therefore down to a handful of pioneering distributors to ensure that the work on the one hand got out there, wherever there happened to be, and on the other encouraged audiences to attend screenings of often unfamiliar and challenging films.

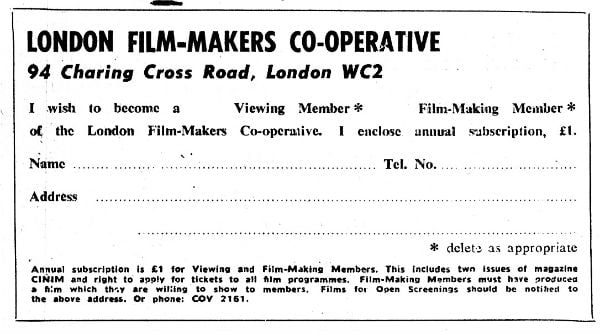

In the recently published Reaching Audiences: Distribution and Promotion of Alternative Moving Image Julia Knight and Peter Thomas set themselves the ambitious task of writing a critical history of these distributors and the British film culture in which they operated, and in many ways helped to create. For anyone interested in the development of an alternative British film culture in the 70s and 80s it makes essential reading. Knight and Thomas focus their attention on nine distributors whose histories overlap and intertwine: the London Film-maker’s Co-op, The Other Cinema, London Video Association (LVA), Circles, Cinema of Women, Film and Video Umbrella, Cinenova, London Electronic Arts and LUX. The book seeks to make these histories visible, whilst stressing their importance in forming and forging an identifiable British film culture. It also attempts to assess the impact that changes in the way the organisations were financed had on what the authors propose was (and is) the key function of distributors: audience development.

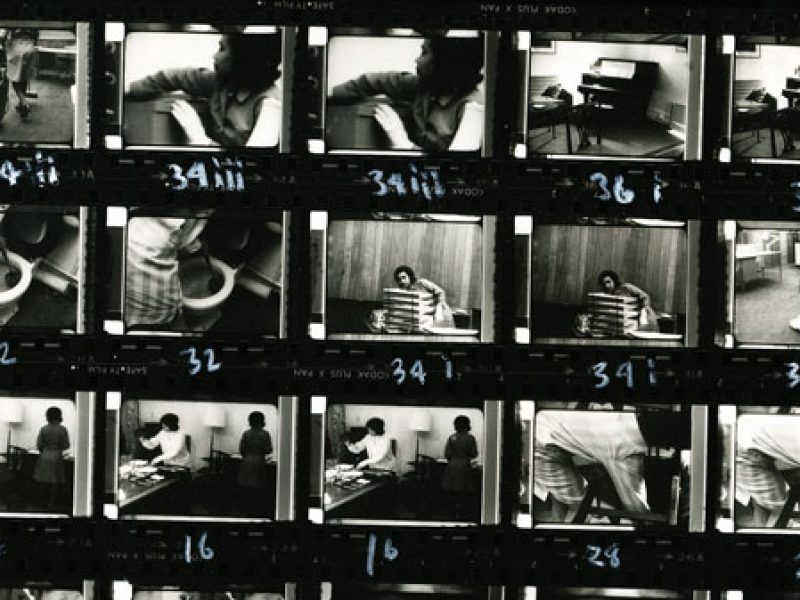

For a period in the 70s and early 80s, film (and then later, video) was the medium for anyone interested in wedding politics and aesthetics, and film theory was the discourse through which to reflect on the suitability of this marriage. This was before the mass migration of practices and discourses to the gallery and museum. Another narrative that can be written about this period – and this is the one that Knight and Thomas insist upon – is the role played by funding bodies in creating a “subsidised economy” and encouraging (at first) and then, dictating the aims and objectives of small scale arts organisations based on national and regional priorities. They narrate this as a move from a “reactive” mode of funding to a “proactive” one, with funders starting to “direct and essentially own the activity”.

In addition to the book, which was published by Intellect Books in 2011, Knight and Thomas have made 100s of documents, which they scanned for easy reference during the writing of the book, available online through the Film and Video Distribution Database. As with the book the documents mainly relate to the distributors mentioned above, though there is the hope that the scope of the database will widen as fellow researchers and archivists add more material. This is one of the crucial components of the database project – the facility for users to input new material, helping the resource grow and evolve.

At the moment much of the material on the Film and Video Distribution Database will only be of interest to fellow researchers. However interesting or dramatic the events or crises covered in meeting minutes are, they will never make for thrilling reading. Trawling through the documents though, it is possible to get a sense of what was felt to be at stake.

Hopefully, as the FVDD grows, it will be possible for other narratives to emerge from the material. And, as it stands, amongst the internal memos and meeting minutes there is the occasional moment when the will of some of the main players (and the ideologies they carried with them into their jobs) shine through the language of officialdom. In an internal memo written by the late Paul Willemen whilst working at the BFI there are visible signs of discontent at the neo-liberal takeover of our cultural institutions. Willemen’s coruscating style strains against the official language of report writing. But after attending a seminar on “building the arts in London’ held at the Royal Festival Hall in 1989 he reports back that it had been a “waste of time from a BFI pov.” How refreshing to read his undisguised horror at the prospect of London boroughs competing against each other to push forward cultural regeneration, “driving up property prices” and “squeezing out low income families […] making London into a solidly Tory area surround by a low income twilight zone.” Through gritted teeth he lists the buzzwords and “PR talk” that littered the presentations of the speakers: “great opportunity… challenges… creative people… benefit to the community… corporate planning… […] unique heritage… planning gain… partnerships”. With uncanny prescience he conjures up the landscape into which will step New Labour: “The most vivid impression I carried away from the day was how thoroughly the Thatcherite approach had penetrated even into the hearts of her opponents”.

There are other key figures whose voices it would be great to hear more clearly such as Marc Karlin, Felicity Sparrow, Laura Mulvey and Steve Dwoskin among many others. It is a fascinating period for so many reasons and hopefully Knight and Thomas’ work will be added to over the coming months turning a useful resource into an essential one. If you are interested in contributing to and developing the FVDD, or if you just want to explore the documents already uploaded please visit the website.

Dan Kidner is a curator and writer. He was previously director of Picture This, Bristol, and before this, City Projects, London. Over the past 10 years he has produced many artists’ films including Fulll Firearms by Emily Wardill (2011),Abyss by Knut Åsdam and The Empty Plan by Anja Kirschner and David Panos (both 2010). His curated exhibitions include ‘Depression’ with Lisette Smits, Marres Centre for Contemporary Culture, Maastricht, the Netherlands, 2009; and ‘Infermental’, with George Clark and James Richards, Focal Point Gallery, UK, 2010. In 2012 he programmed a Marc Karlin retrospective, and in 2013 edited the book Working Together: British Film Collectives in the 1970s.