Georg Lukács wrote that the essay is a form of judgment, but one whose value resides in the process of judging rather than in any verdict that one might draw. This statement absolutely holds true for the essays of artist and theorist Hito Steyerl, whether they appear in print or on screen.

In videos such as November (2004), Lovely Andrea (2007), and In Free Fall (2010), Steyerl works within a tradition of highly discursive, found-footage production engaged in interrogating the politics of the image. She is best understood as part of the long tradition of politicized essay filmmaking, a lineage that goes back as far as D.W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909) and that has often taken up the status of the image as a specific point of interrogation. The filmic references littered throughout The Wretched of the Screen, a collection of her texts recently published by Sternberg Press, bear this out: Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas’ La hora de los hornos (Hour of the Furnaces, 1968), Dziga Vertov, and Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1976) all make appearances. And yet Steyerl’s work evinces key differences from such filmmakers: it not only displays a notable sense of humour and investment in pop culture, but also circulates in a very different institutional context, that of the art world. In Fall 2012, for example, Steyerl had her first solo exhibition in the United States at e-flux in New York City; her second was recently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago. A new video, Adorno’s Grey (2012), incorporates installation components in a substantially more elaborate fashion than anything she has made before, including grey carpeting and a projection surface constructed from four large boards that fractures the image plane. Steyerl’s work further departs from many of her precursors in the rhetorical mode it privileges. Her videos and texts are less concerned with advancing a definitive thesis than they are in staging a series of provocative analogies in order to see what new insights might be gleaned from them. Questions take precedence over answers. As Steyerl diagnoses the affects, impasses, and opportunities of the neoliberal experience economy and the place of the image within it, one is frequently reminded of the caution Gilles Deleuze offers in his “Postscript on the Societies of Control”: “There is no need to fear or hope, but only to look for new weapons.” Steyerl neither condemns nor endorses the phenomena she observes around her; one finds neither nostalgic despair nor technoromantic euphoria. Rather, her body of work furnishes what Franco “Bifo” Berardi calls in the introduction to The Wretched of the Screen “a cartography of the emerging new sensibility.”

Perhaps no other part of Steyerl’s work captures this “emerging new sensibility” as deftly as her notion of the “poor image,” a concept that is threaded throughout much of her practice. The poor image is a low-resolution image that is compressed, artefacted, cropped, and blurry – but quick to load. It is a copy that indexes its travels, that registers visually the goal of reaching as many viewers as possible, even at the cost of pictorial integrity. In the same gesture, it contests both the hubris of high resolution perhaps most embodied in Peter Jackson’s recent HD-3D-48-fps catastrophe and the analogue loyalism of a project like the Temenos. For Steyerl, the poor image is exemplary of our contemporary visual culture. For every gigapixel image of Google Art Project, there are millions of blocky JPEGs. “A copy in motion,” it dramatizes the inverse relationship that inheres between accessibility and quality: the lower resolution the image, the smaller the file size, and the more able it is to circulate.

In his recent book, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, Jonathan Sterne unsettles the linear narrative of technological progress that understands media technologies as developing along a path of progressive fidelity to ask: “If we have possibilities for greater definition than ever before, why does so much audio appear to be moving in the opposite direction?” It is not just audio that is moving in this direction, but often images as well. For Sterne, examining the MP3 opens the door to another kind of history of new media, one that would not be a history of increasing resolution but instead “a general history of compression.” In visual culture, attention to the poor image offers a similar opportunity to formulate a media history in which images abandon the quest for high definition and in which transmissibility is key. It also provides a way of highlighting how often images traverse the ever-fainter line between sanctioned use and unauthorized shadow economies. It is a history that extends back to the practice of producing etched copies of oil paintings, through the fading toner of Xerox machines, the smeared colours of dubbed VHS tapes, and forward into our present, where it erupts with a new and special force, filling our everyday screens and our galleries, too.

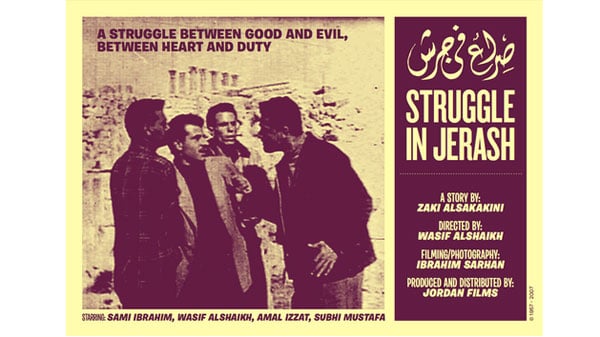

Ben White and Eileen Simpson’s Struggle in Jerash (2009) stands as a particularly strong example of the way that contemporary artists have engaged with the circulation of low quality images. Invited in 2008 to a residency at Makan House in Amman, Jordan, to undertake a project concerning the resources of the public domain in that country, Simpson and White became interested in the 1957 film Struggle in Jerash (Sira’a Fi Jerash), directed by Wasif al-Shaikh, which had fallen out of copyright that year. Set in Jordan and Jerusalem and made by a group of independent filmmakers of Palestinian descent, Struggle in Jerash was the first feature film produced in the country, which had gained independence from Great Britain just over a decade earlier in 1946. In the absence of an official archive, Struggle in Jerash had no clear guardian; a low quality VHS tape is all that was left of a crucially important text in Jordanian film history. The artists digitized the VHS copy and used the transfer as the basis of a new, sixty-minute work. The image-track of the video consists of the 1957 film played in its entirety. The picture is extremely degraded, both from significant damage to the original 35mm print and from its transfer to VHS tape. There are numerous scratches and blotches of decay, and sometimes the analogue video scan lines become visible. Simpson and White’s intervention occurs on the soundtrack, which consists of the voices of twelve Jordanians who comment on what they see in the film. The artists appropriate the convention of the director’s commentary track – usually used to regulate the meanings attached to the text via the reassertion of authorial control over “proper” signification – to document the various reactions Jordanian artists and intellectuals have today to their country’s first feature. Simpson and White then reinserted the film into the most widely used distribution circuit for feature films in Jordan: the market for pirated DVDs. They made use of an unofficial form of circulation to return a part of the country’s audiovisual patrimony to its people in the absence of state-initiated efforts at preservation and dissemination.

As the example of Struggle in Jerash suggests, there are instances in which the degraded copy can absolutely fulfill the possibilities that Steyerl discerns within it. It can “constructs anonymous global networks just as it creates a shared history,” it “builds alliances as it travels, provokes translation or mistranslation, and creates new publics and debates.” But it is important to remember that there are also times when a poor image is just a poor image, maybe making someone richer. With a nod to Frantz Fanon, Steyerl calls the poor image “the Wretched of the Screen, the debris of audiovisual production, the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores.” Such images may indeed be detritus, long detached from any identifiable origin, circulating as fragments outside the official, monetized channels of online distribution. But as much as they are the trash of the digital economies, so too are they its nourishment; though Google does not release revenue reports for YouTube, Citigroup’s Internet analyst Mark Mahaney estimated its gross revenue at US$3.6 billion in 2012. The pixelated cuteness of someone’s corgi doing a bellyflop into a lake may be low quality and user-generated, but it is also revenue generating. This is not lost on Steyerl. Though the title of her essay, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” might intimate that she is engaged in a polemical valorization of this often-maligned form, the text in fact sketches a profound ambivalence. While Steyerl champions the possibility that the poor image might serve as an index of social relations and aid in the recirculation of material that might be otherwise very difficult to access, she also acknowledges that it possesses a Janus face: “On the one hand, it operates against the fetish value of high resolution. On the other hand, this is precisely why it also ends up being perfectly integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation, on previews rather than screenings.” The long history of thoroughly commodified low-quality copies should make one hesitate before assigning any particularly revolutionary attributes to their digital counterparts. As an increasing number of artists embrace Steyerl’s theory of the poor image, often as an aesthetic rather than as a part of a deeper engagement with the politics of circulation, the inherent ambivalence of the concept risks being left behind. To fasten solely onto the endorsement suggested by the title of “In Defense of the Poor Image” is to misrecognize not only Steyerl’s argument, but also what is at stake in thinking through the status of low quality digital copies today.

Erika Balsom is assistant professor of film studies at Carleton University and author of Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, forthcoming this spring from Amsterdam University Press. Her brief history of the limited edition as a model of sale, “Original Copies: How Film and Video Became Art Objects,” will appear in Cinema Journal this summer.