As part of its Essential Experiments series, the BFI dedicating a session to the sixties films of Anthony Stern on the 16th of September 2014. Stern worked closely with Peter Whitehead in the sixties and he also shot his own playful 16mm titles. Infused with the spirit of the psychedelia and the French New Wave, they paint a joyous picture of the 1960s counter culture as it came into full dizzy bloom.

– Your first experience with film was working with Peter Whitehead, could you tell us about how you started working with him?

It was one of those accidents that happen in life. I was a student in Cambridge. I bumped into this man in the streets, all the books I was carrying fell on the floor. It was Peter. He helped me to pick them up and asked me ‘Are you free this afternoon?’. So I went with him and helped him with a film project called The Perception of Life (1964), a film about the discovery of the DNA. That was my first chance to see how a camera works. We went on to work together for a few years.

– What kind of film-work did you do with him?

I left Cambridge in 1966 and went to live with him in London, in Soho, in very bohemian conditions. Peter taught me everything I know. He clothed me and fed me. His films were a two-man job really. In 1966 we followed the Rolling Stones on their tour of Ireland, we filmed their concerts in Dublin and Belfast and this is how we made Charlie is My Darling, the first documentary about the boys. It was a black and white experiment. I assisted Peter in this adventure and worked on the sound. With Peter I first did sound recording and then, later on, camera work. We did various films those years, pop films. We worked on short films for the Wednesday evening Top of the Pops, a very popular TV show at the time. We also worked with the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones on other occasions. Working with Peter I met a whole series of interesting people, the makers and shakers of the 1960s. There weren’t that many of them, we got to meet them all. Making films is a good way of meeting people.

– You made Baby, Baby, your first film, in 1965. It is an autobiographical film in which the visual and sonic experimentation are already present. How did that film come about?

I had worked with Peter for a while and I decided to make my own film, a portrait of my own life. It is a film that was made in a very intuitive way, but it was more farsighted than what I could recognise at the time. Seeing it now, I see it is as a miniature of the later work. My girlfriend was having a baby at the time, and it seemed like a good subject for me to talk about that experience of becoming a father. It is a film that juxtaposes adolescent sexual fantasies with the reality of procreation. You also have a shock, at the end of the film, with that unexpected scene documenting the delivery of the baby. I did love film from then onwards as a way of diary keeping and visual experimentation. From then on I worked on my own things while working with Peter.

– While making films, you also worked with various bands doing lightshows, could you tell us about the music scene of the time and the work you did for the bands?

The truth is I was a frustrated musician, but I found ways of contributing to the show. I did lightshows and films that we projected on the bands. I worked on live film projection. I did lots of work with a British rock band called The Move and I worked at the UFO Club for a while. I worked on this with Peter Wynne-Willson who did the first lightshows with Pink Floyd using wet slides. I remember Peter doing ink mixing tests for the slides he would later project at UFO. It was a very inky business but the results were wonderful: crashing galaxies, microscopic universes.

– Your films can also be seen as experiments in which the combination of sound and image creates a new experience for the spectator.

That is what psychedelia is for me: an essential fusion, or confusion, of the aural and the visual that activates a creative spark. You open the portals of the eyes and the portals of the ears and something happens inside where they came together. It is a kind of explosion that takes you outside your head and a third art form happens. The experiments at UFO performed by Pink Floyd and Peter Wynne-Willson were the first fusion of music and image where ultimately neither was complete without the other. I had worked as a professional cameraman for a number of years. I learned how to do things properly and then I learned how not to do things properly for myself. We wanted to make a new kind of film. We talked of making non-narrative films in which all parts would relate to all other parts like a geodesic dome.

– Your film San Francisco (1968) is a radical example of this psychedelic synesthesia you are talking about. Could you tell us about the context in which you made San Francisco?

I was in New York working with Peter Whitehead on The Fall (1969), which I think is his best film. After we finished I wanted to go to San Francisco. San Francisco was such a buzzword then… a word of light and energy. Two friends of Whitehead who liked me gave me some money to get me started with this project of filming the San Francisco scene. The film is a record of what happened to me, the record of an adventure. I was trying to do two things with this film: to make a musical film and also to keep a record of events. But really, there was no theory behind the film. I wanted to experience what San Francisco was all about. The camera was a way of doing that. I used the camera in a very free way. It would not have worked if I had had a script. It’s a film with an explosive energy and freedom.

– San Francisco is very masterful in its use of the in-editing. Could you tell us about the technique you used to film and edit?

Peter Jenner, then their manager, had given me a reel-to-reel tape of a piece of music by Pink Floyd and told me to do whatever I wanted with it. It was Interstellar Overdrive. It is a unique live recording, the first version of the track ever recorded. When I went to San Francisco, I had the music in my head. I made the film with the music in my head. When it came to filming and editing, my technique was always to cut the boring bits, not to waste screen time. There is to be nothing superfluous, reducing and reducing the film until it explodes. I did editing in camera, it is great fun and easy to do. It is a way of filming that is like dowsing, like swimming. You put yourself in the right place at the right time, and it becomes a dance in which you can anticipate the movements of reality. On the other hand, well, film was very expensive and I was an independent filmmaker. So I thought of recording these events with single frames instead of 24 seconds and then expanded them later on.

– The film is also a document of the American counter-culture of the time.

When I made it, there was no notion that a film like San Francisco was a document of its time. It is very much a film about the heat of the moment, the raptures and ruptures of that moment. We see a concert of Pink Floyd, there is the so-called orgy scene with the people from the San Francisco Mime Group. In the film this orgy scene is important, because it is suddenly like a focal point in the constant movement of the film. They perform a bogus ceremony, very much in the style of what we called then ‘the hippie charade’: they offer things to this object, and early version of a computer, and then it all disintegrates. It was not a sexual thing, but an amusing ceremony, an attack on the system done in a fun way. It is a scene that encapsulates the San Francisco of the time: the dressing up, the drug-inspired behaviour, the sexual liberation, the self-indulgence, the fun…

– The film was backed up by the BFI, how did they help you?

When I came back from America this famous chap, Sir Michael Balcon, who was a film producer at Ealing Studios involved with the BFI, saw the material I had and he immediately understood it was a great film. He said: ‘This is the kind of film we should be making at the BFI! Wonderful, wonderful!’. To receive that kind of affirmation from an older generation of filmmakers felt really good. He saw in San Francisco a new direction for film, fragmented, multi-layered and so on. So thanks to him the BFI gave me some money to finish the film. Hats off to Michael Balcon and Bruce Beresford, who headed the Production Board then, for supporting such an experiment!

– And how was the film received? Where was it shown, what opportunities existed back then to see such experimental films?

San Francisco was essentially despised in the UK, but it got some prizes in the festivals at Oberhausen and Melbourne. In general our films were not shown. This country is terrible for filmmakers. This lack of exposure is not very encouraging to continue. There always was an underground scene of course; things were not so grim. San Francisco was shown by the BFI once. It was shown a couple of times at the ICA. There were some private screenings, for friends, in a very small scale. It is different in other countries. My films have been shown in television in Sweden, Germany, in France I think… not here. I think it is a matter of fear, we are afraid of seeing something that we do not know how to categorise. The work of Whitehead was also neglected back in the sixties, never shown.

– And yet, in spite of this lack of exposure, after you managed to continue making different types of films, for instance your architectural film, Serendipity (1971).

To continue making films I used San Francisco as a visiting card. That is how I got a commission to make Serendipity. It was made for the International Building Exhibition. They gave me two thousand pounds to do it. It was shown during their exhibition in a cinema booth. It is a film about British modern architecture, but I was not interested in what you see, the buildings, but in how to see these buildings – ways of seeing more than what we are seeing. It is quite a playful film, the buildings dance… I showed the film to a music composer, Barbara Moore, who got some musicians together and they did a jam session. That is what you hear, a live recording inspired by the images. Today this playfulness with the buildings would be impossible; it would be deemed ridiculous!

– You have also done some film-portraits of your friends, of Peter Whitehead in Nothing to Do With Me (1968) and of the American poet Ted Berrigan in the homonymous film (1970).

Yes, Ted came to stay at my flat. He was a great talker, with a strong presence, and I wanted to film him. We made a film portrait. He found filming a bit trivial or superficial, but he went with it. I didn’t know his poetic work too well. I just knew him as Ted, as a friend. In New York he used to be worshipped as this great poet of the New York School. For us in the UK it would be vulgar to worship someone like that… Never put anyone in a pedestal, only Jimi Hendrix [he laughs].

– It is significant that you did not repeat the style and technique of San Francisco. Although there are resonances between the films they all have their own pace. For instance, you have described your film Wheel (1969-1971) with the following words by Buckminster Fuller: ‘inherently regenerative energy association events’.

Yes, that line of Fuller became my mantra, and it summarises perfectly what I was trying to do with that film. The idea of ‘association of events’ was behind my impulse to do that film. The BFI refused to give me money to finish editing it. Those in charge then did not get at all the idea of a film with a non-linear narrative. It is a film composed of symbolic moments of my own life. It is a shared diary, but also a universal diary. I remember showing the film to a friend of mine who had had a radical experience in India. Something happened to her in the presence of the Dalai Lama there, the intensity of his presence affected her deeply, and she had to be taken back to England and be hospitalised. When she came out of the hospital she came to visit me. I had one of the walls in my flat covered with images from Wheel. She stared at those images for a long time, and she said ‘you are showing my life’. For me that was the best compliment, it is a film about anybody’s life.

– And then in the mid seventies you abandoned film. You became a recognised glass artist, and you have a glass studio that is still running. Is there a connection between glass and film?

Moving from film to glass was one of the most interesting shifts in my life. In 1976 I went to the Royal College of Art, where I became a glass blower. The main reason was that I wanted to have control over what I did. The problem with film is that there is always a legal side, getting rights to use materials, music. That was always a nightmare for me. Glass was a great alternative to film, it has many similarities with film. Film and glass are both translucent materials through which light passes. The aesthetics of transparency always attracted me: in film, in the lightshows, in glass. Looking at glass is like looking at a film. Most of my glass pieces have a cinematic quality to them, and vice versa. My glasswork is always thought to have light pass through it. A glass studio is also a bit like a film crew.

– In the past decade you have gone back to making films (Havana Jazz, 2006; Dancing with Glass, 2013), how did you go back to making films?

I injured my back and I went back to film, to small-scale filmmaking. Films I can make in my own territory. Making film-poems is the way forward. Nicole Brenez has been a great help; she saw some footage of mine and tracked me down. She has shown my work at the Cinematheque in Paris and has been a great supporter.

– Going back to making films has also meant going back to your archive of images and film footage. Could you tell us about your archive and the projects that you are developing with it these days?

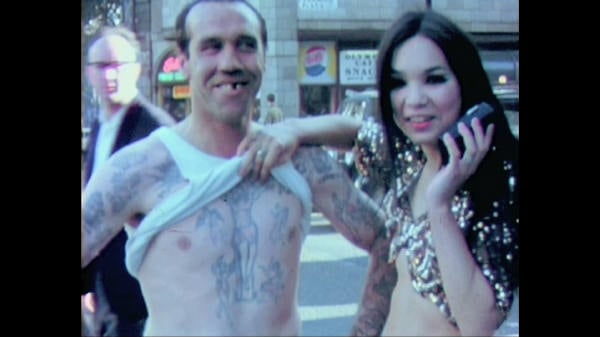

My archive is an accidental one; I just did not throw things away. I have thousands of photographs and many cans of films from the 1960s. There are things I forgot I had done and I am now re-discovering. One project is almost finished; I just have to sort out the music. It is called Did You Get That Ant?. It is a film made with photographs and film clips. It shows life in the sixties in London. I also have a lot of material about Pink Floyd that I found in a can in my cellar. I am thinking of doing something with it, it is stuff no one has ever seen. I have also been revisiting the material I shot for San Francisco and that I did not use. There are wonderful things: very abstract images of a concert of B. B. King in Winterland, San Francsico music venue, scenes with my friend Tiger Morse (who was part of Warhol’s circle), images of communes, street life… It is a document of the 1960s in America. We are going to show some of this American footage for the show at the BFI Southbank this September.