At the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, Ranjit Hoskote curated the Indian Pavilion, titled Everyone Agrees: It’s About to Explode. Amongst the various works presented was Kerala-born, New Delhi-based artist Gigi Scaria’s Elevator from the Subcontinent (2011). Scaria’s work was a three-channel video installation in which viewers pressed a button and entered a model elevator that simulated the illusion of movement. The work had a linear narration, starting in a parking lot, then ascending upwards through the interiors of various apartments, finally arriving at the top of a building. This is followed by a free fall back to the parking lot, and then into the basement where a few more living quarters are seen, proceeding underground and eventually arriving back at the parking lot.

Scaria’s use of the multi-channel installation to envelope the viewer attempts to not only visualize, but also rather emphatically draw attention to the diversity of the social life of the Indian metropolis. It points to the hierarchies and stratification inherent within it, which now seem to be susceptible to all kinds of mobilities and migrations as its economic landscape changes. The work gamely and proficiently elucidated a curatorial conceit that significantly rallies against the idea of a singular, national culture.

This creation of a bespoke environment in which multi-channel video projections are used to envisage the multiplicity of Indian social life and engender an experience of its plurality is certainly a strategy with historical precedent extending beyond the 1990s, when Indian artists actively started developing and presenting installation-based work that incorporated film and video. It led me to wonder, what were the first kinds of experiments with multi-channel projection in India? When did these take place and under what circumstances? I would like to propose that there are two moments – one from 1967 and the other from the early 1970s – which should seriously be considered as amongst the earliest attempts in devising multi-channel experiments, and which figure as active additions to the prehistory of new media practices in post-independence India.

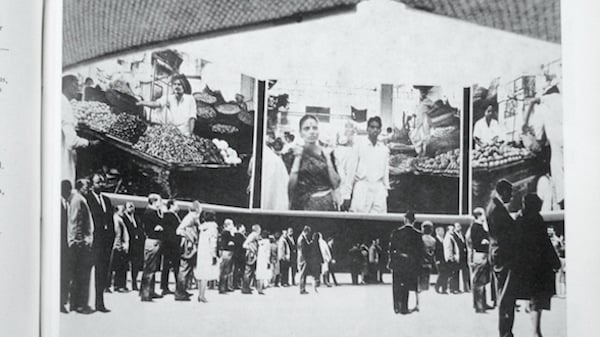

The first of these occasions is the 9-screen projection Dashrath Patel conceived and executed for the India Pavilion at the Montreal World’s Fair in 1967. Patel was a multi-disciplinarian, having worked in painting, design, ceramics, architecture, printmaking, engraving, photography, and stage performance. He was the founding secretary of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, where between 1961 and 1980, he occupied a number of different positions. During this time, Patel interacted with numerous international personalities such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Charles and Ray Eames, Buckminister Fuller, Louis Kahn, Frei Otto, John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg. Also, for nearly two decades, from 1964-1986, Patel was the chief organizer of every official India Exhibition abroad, which included the Festivals of India in France and the USSR, and the India Pavilions at the Tokyo, Osaka and Montreal World’s Fairs.

Sadanand Menon, a dear friend, recalls Patel’s process in developing the 9-screen projection for the Montreal fair:

There is a moving story how in 1967, Dashrath coped with his own dream of creating a 9-screen 360 degree projection of a Journey In India for the India Pavilion at the Montreal Art Fair, with no access to hi-tech equipment. Faced with the task of having to create a ‘circarama’ effect, he devised a plywood housing for nine cameras which he would wear around his neck. Linked to a single remote shutter-release apparatus, the cameras facing different direction would go off simultaneously to create the effect of ‘shooting-in-the-round’. He travelled through India with this collar of cameras around his neck. The 30,000 images he shot were edited down to 1,600 and beamed through a console of 18 carousel projectors. Dissolve technology was not available. Dashrath tackled the problem of fade-in/fade-out on the spot at the exhibition by rigging up slave-motors to drive mechanical flaps that would create the effect of the dissolve.

Marg, an Indian arts magazine, featured this project in its June 1967 issue, Design for Living. It lists the Handicrafts and Handlooms Exports Corporation of India Ltd. as the client, and states that Geeta Satyadev Mayor arranged the accompanying music for the piece and Benoy Sarkar did the graphic design. It also catalogues other precise details about work, from the screen sizes and which kind of projectors were used, to how the fifteen-minute show was divided and sequenced. It concludes by stating that “more than all Journey in India seeks to portray the values that New India cherishes.”

It cannot be denied that Journey in India was formally inventive and quite unique coming from an Indian context, and is undoubtedly a predecessor to Scaria’s Elevator from the Subcontinent, Patel was tackling the issue of how to project, literally as well as conceptually, the cultural mix and richness of India. The plethora of images, were divided into three parts, the first a sequence of 33 (of nine slides each) focused on geography and people, the second, a sequence of 42 depicted the arts and crafts, while the third consisting of 40 sequences, concentrated on the new post independence modernizing efforts that had been initiated. Undoubtedly, for an international audience the juxtaposition of images from the length and the breadth of the country would prove alluring, along with the demonstration of how the age old seems to be sitting harmoniously with the new and modern. The project with its grand sweep, seems commensurate with the times, and the nations own anxiety to reflect and enact the success of its transition from colonial to the post colonial, without comprise and a violent denial of its history.

However, from today’s vantage point of view, trying to grasp the work through scant archival documentation, and not being able to experience it, can it be suggested that while being an encapsulation of the nations aspiration, did a Journey in India through its sheer excess flatten out the diversity it so desired to convey? Was it simply a performance, rather an articulation or did it transcend the cultural diplomacy of a World Fair and really enable a foreign audience to reshape and form a more nuanced understanding of the country? Journey in India is an arresting configuration of national ambition, individual ingenuity and technical resourcefulness, and its relevance as part of a prehistory of Indian media art, cannot be denied. By making this acknowledgment, Patel and his absence from most accounts of Indian modern art becomes even more glaring. Patel is one amongst a group of postcolonial Indian artists who, by not aligning themselves to a particular school or artistic movement and by having ‘promiscuous’ practices, have remained marginalized, forgotten, or more appallingly, discounted.

The second instance of the use of multiple media audio formats in a local Indian context was a series of events based on rock music that incorporated slide and film projection and live performers. Called Thru Pablo’s Eyes, these events were organized by the photographer Pablo Bartholomew and took place in the early 1970s, a period in which Bartholomew was intensely photographing his friends and recalls as “when the Hippie era was ending, but there was lot of frantic listening to music, all the big rock groups.” Bartholomew’s parents, the art critic and photographer Richard Bartholomew and his wife Rati Bartholomew, the noted theatre personality, were at the time in New York on a Rockefeller fellowship, and would send LPs back home with whomever was travelling. There was always a delay between when the album would be released and its arrival in India.

The first installment of Thru Pablo’s Eyes oriented itself around the album Jesus Christ Superstar (1970). After listening to the record, Bartholomew thought of and connected it to classical painting that dealt with Christian themes. It was around this premise that he formulated the first chapter that took place at the YMCA in New Delhi, which was comprised of three slide projections and the album playing. The projected images ranged from Leonardo Da Vinci, El Greco, Raphael, Sandro Botticelli, Hiernymous Bosch to the surreal paintings of Salvador Dali. With these images, Bartholomew was building associative links, and animating underlying currents he detected within the music.

This was followed by the second chapter, which used The Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as its focal point. More multifaceted, Bartholomew drafted in live performers. For example, during the song She’s Leaving Home, he had a female friend become an actual embodiment of the song, dressed up in Hippie garb, sitting at a table, waiting. Alongside, he would project the colour images his father had shot from his apartment window in New York of its street life. India itself was not the reference point, but rather it was an engagement with the international, a conversation with the West, that seemed to being set up. Bartholomew notes that the number of westerner travellers to India increased in the 1970’s, post Vietnam, they “came overland to India and discovered the mystical land of drugs and timelessness. In a sense an escape from the more material home and regimentation that he or she encountered. With them they brought their music and their lifestyle of hair, habits, dress and music. All of this was a big influence on us here and there was a lot of interaction.”

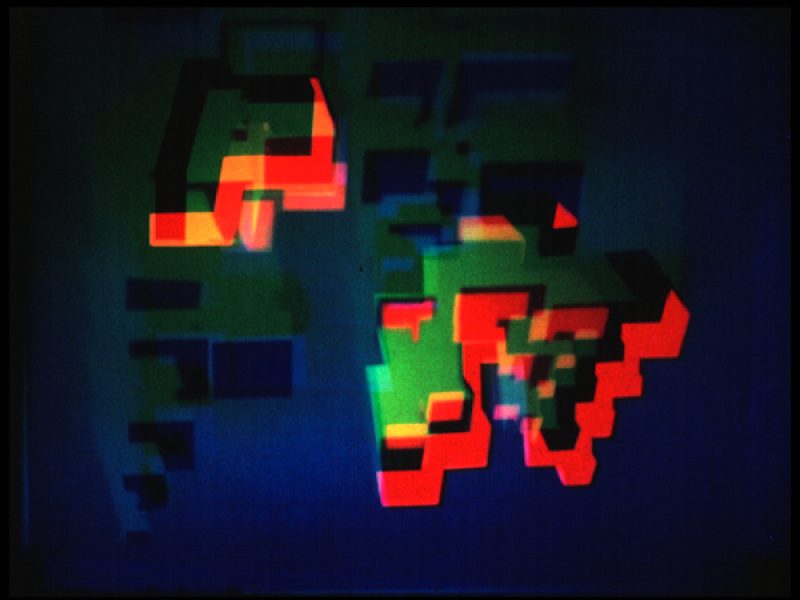

Building on the success of this chapter, he would conceive the third installment in which he collaborated with the Theatre Action Group (TAG), founded by the theatre director Barry John, with whom he had a lose association. By far the most ambitious, this chapter was built around The Who’s Tommy (1969). Bartholomew remembers that the album came with a fair amount of literature, a book filled with illustrations, so he used this source material to embellish his efforts, which he playfully described as being “totally plagiaristic.” For this edition, Bartholomew also borrowed films from the Canadian embassy. The National Film Board of Canada had a small library that rented out documentaries, but amongst their selection were the films of Norman McLaren. Drawn to the Op Art effects of McLaren’s films, Bartholomew projected them during the event.

Bartholomew’s methodology for the series was organic and did not follow a fixed format. The appropriation of material was from several sources, shown in a variety of formats that he personally seemed to think related to the music, sometimes moving from the literal and illustrative to the more abstract and subjective. Bartholomew elaborates that:

On a personal level, I was experimenting with the techniques and ideas through photography. Through the darkroom at home, having mastered the technical skills, I used these to be able to copy material from books & magazines with finesse and note that in the analogue age you needed to be very precise in your exposure especially with colour slide material which was scarce to find and very expensive. On the other hand playing with ideas and aesthetics by creating opportunities to work with the narrative form and have fun building small photo stories for your own projections. It was using the then current technology to it’s maximum and for a growing teenager about to go into his twenties it was a great kick. I have to add that with a mother in theatre who was a founder member of English language Yatrik and the noted Hindi theatre group Dishantar, I did a lot of backstage work which included lighting and music. Not to mention that I photographed many of these plays so it was all in familiar terrain that this was planned and played out in Delhi till I took it to Bombay and collaborated with the younger generation offspring’s of Theatre Group wallahs and showed with them at the Bhulabhai Desai auditorium.

When queried about the number of times these events took place, Bartholomew relays that he only managed to stage them between two and three times each, but he did travel Jesus Christ Superstar and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to Bombay. The entire series was funded and produced independently, without the support of any external agencies or recourse to government funding. Bartholomew would steal some of his father’s film and copy the other projected images from books and magazines. When the USIS refused, Max Mueller Bhavan was helpful enough to lend him a 16 mm projector. None of the events received any press coverage, but Bartholomew does emphasize the presence of a very receptive audience, not only of fellow artists but many college-going students who were interested in music. There is no film or video documentation of the happenings, except for some of Bartholomew’s own photographs taken during rehearsals, and a poster designed for the Tommy edition. Quite clearly, Thru Pablo’s Eyes was as series of multi-media happenings that had few correlatives within the Indian artistic landscape. Would it be too tenuous to think of it as being in some way related to the Expanded Cinema practices taking place in America at the time?

When thinking of Patel’s Journey in India and Bartholomew’s Thru Pablo’s Eyes today, their progressive use and integration of multi-media in an environment where access to technology was scarce and no market solutions existed is striking. But these works also raise a breadth of concerns that aid in animating for us the world of India at the time. Patel’s work was made for an international audience, supported and funded by the Government of India, and was preoccupied with formulating an image of the nation. Meanwhile, Bartholomew’s series, which circulated locally and was realized in a parallel domain of fewer resources, is an expression of a young man’s interface with counterculture, rock music, and a world at large beyond the borders of India. One should not detect or set up an artificial opposition between them, but rather deliberate on them in comparative terms, as generous evidence of the shifting understandings and visions of a nation itself, but also of its own highly individual artists as well.

(Acknowledgements: I am very grateful to Pablo Bartholomew for taking the time to talk with me, and to Ram Rahman for informing me about Thru Pablo’s Eyes)

Sadanand Menon, ‘In the Realm of the Visual’, in Sadanand Menon ed., In the Realm of the Visual: Five Decades 1948-1998 of Painting, Ceramics, Photography, Design by Dashrath Patel (New Delhi: NGMA, 1998) page 20.

‘Multiple Projections at Indian Pavilion Expo ’67, Montreal’, Marg, Vol. 20, No. 3, (June,1967), 50.

Conversation with the artist on the 6th of April, 2014.

Ibid.

Ibid.

E-mail correspondence with the artist, 29th May, 2014.

Shanay Jhaveri is the editor of Outsider Films on India: 1950 – 1990 (The Shoestring Publisher, 2010) and Western Artists and India: Creative Inspirations in Art and Design (Thames and Hudson, 2013). He has curated film programmes at the Tate Modern, Iniva, LUX/ICA Biennial of Moving Images, and the exhibition Companionable Silences at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. He is a contributing editor to frieze magazine, and is currently a Phd. Candidate at the Royal College of Art, London.

Image credit: Dashrath Patel’s 9-screen projection for the India Pavilion at Montreal World’s Fair 1967 and Ranesh Roy as Tommy in a rehersal for Pablo Bartholomew’s Thru Pablo’s Eyes. Copyright and Courtesy: Pablo Bartholomew.