In the efflorescence of 1970s film culture in Britain, the documentary held an ambiguous place.

Theorists and writers suggested that the documentary form was rooted in reactionary forms of realism, naïvely empiricist and ideologically complicit (Garnham, 1972; Willemen, 1972; MacCabe, 1974); they called for new forms and berated those that didn’t measure up (Johnston and Willemen, 1975). Nevertheless, within film practice itself, there was a compulsive return to the non-fictional, the non-diegetic and the social – the very fabric of documentary. Groups such as the Berwick Street Film-Collective and the London Women’s Film Group effectively reinvented the documentary form under a new rubric of avant-garde experimentation injected with a radical social vision. Others, including Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, created films whose subject was ‘the real’ (for example, Riddles of the Sphinx is deeply concerned with the issues of childcare and the workplace), yet which undertook the task of creating a counter-cinema that opposed notions of both the fictional and the documentary.

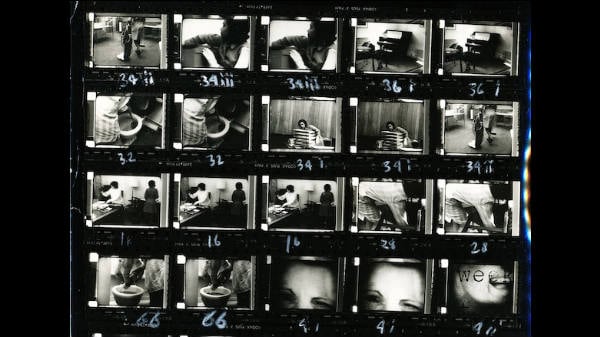

The 1970s and ’80s produced a number of highly innovative works that we would generally describe as ‘documentary’ and that are increasingly regarded as canonical – these include Nightcleaners, The Song of the Shirt, Riddles of the Sphinx, So that You Can Live! and Handsworth Songs. This canon-formation is evidenced by increased institutional support: for example, Nightcleaners was screened at Tate Modern in Spring 2013 while Handsworth Songs was acquired for the Tate in 2009.i There is a robust return to the documentary-as-art today, with numerous younger artists taking up the mantle producing works in a range of deconstructive, performative and observational modes, and a number of new publications devoted to the subject (Demos, 2013a, 2013b; Stallabrass, 2013).ii The form seems at once acceptable as art and understood as an open, evolving and innovatory form with a radical heritage.

Our contemporary enthusiasm for all things documentary was not evident in the 1970s. Indeed, it should be noted how rarely the word ‘documentary’ was used to describe non-fictional film in journals such as Screen, Afterimage and Cinema Rising: other terms were generally preferred such as ‘Newsreel’, ‘militant’, ‘collective’ and ‘independent’.iii To understand the hostility to the documentary felt by many theoreticians and film-makers at that time, we must begin by unpicking some historical threads. Firstly, it should be noted that many British intellectuals on the left viewed the documentary as part of a retrograde and elitist English culture – the establishment culture. In this sense, criticisms of documentary were wrapped up in an internationalist, anti-nationalist intellectual climate of the New Left.iv These criticisms first crystallised in the mid-1960s, particularly in Perry Anderson and Tom Nairn’s writings in the New Left Review. In 1964, for example, Nairn railed against:

English separateness and provincialism; English backwardness and traditionalism; English religiosity and moralistic vapouring; paltry English ‘empiricism,’ or instinctive distrust of reason …”v

Perry Anderson diagnosed the problem in his essay ‘Components of the National Culture’, in which he argued that existing critical frameworks were problematic due to their inability to think about class (Anderson, 1968).vi For many Screen writers, the British documentary was similarly rooted in a reactionary nationalism. Indeed, John Grierson, Humphrey Jennings and the BBC documentary department had all stressed the harmonious unity of the classes working in the service of nation, empire and industry. In 1972, Nicholas Garnham wrote of ‘that tradition which saw “the documentary” as the art cinema of Britain’, and found that it was used ‘unchallenged to support the status quo’ (Garnham, 1972, pp.109–110). In 1974, Alan Lovell noted the ‘basic conservatism of the British Cinema’ while Colin MacCabe compared Lindsay Anderson’s very English film O Lucky Man! with Godard’s refreshingly European Tout Va Bien (MacCabe, 1974).

Beyond parochial conservatism, the second major problem for documentary was that of realism. For MacCabe, the ‘classic realist text’ might be either fictional or non-fictional, but – either way – it was structurally unable to understand ‘contradiction’: i.e. the conflicting interests of the bourgeoisie and the working class (MacCabe, p.12). MacCabe here echoes a broader counter-cultural position that emphasised the need to provoke social contradictions through a radical conjunction of formal experiment and political content.vii Writing in 1972 in Cinema Rising, Jim Pines noted that ‘militant-political-revolutionary cinema has to be aimed at provoking social contradictions, and to the extent of alienating sectors of the audience from one another.’ Pines goes on to state that ‘… the majority of political films shown in Britain have been essentially informational and far from political’ (Pines [1972] in Kidner and Bauer, 2013, p.84).

By the mid-1970s, Claire Johnston and Paul Willeman went further in admonishing radical film-makers whose work had not broken from realism:

In Britain collective film-making practice, despite its achievements (which have been considerable), has been particularly affected not only by the manipulation thesis and the assumptions of the classic realist text, but also by wider political misconceptions about the nature of working-class culture. (Johnston and Willemen, 1975)

Within this melee of anti-nationalism, avant-garde aesthetics and revolutionary provocation, the documentary became something of a taboo word.

For all this much-need criticism of the status quo, documentary production actually fared relatively well in the 1970s. Christophe Dupin notes that during Barrie Gavin’s time as Head of Production, the BFI Production Board moved away from feature films to the production of documentaries, and 12 of the 32 films produced under his stewardship were ‘political documentaries’ by groups including Berwick Street Collective, London Women’s Film Group and Newsreel (Dupin, 2012, pp.197–218). Meanwhile, the Other Cinema distributed a wide array of independent documentaries, alongside avant-garde and fiction films. By the 1980s, Channel 4 was funding an increasing number of documentaries through its Eleventh Hour strand – one of which was Handworth Songs.

These notes are tentative, but it seems to me that the experimental works actually produced during this period managed to undo the equation of documentary with Britishness and a retrograde form of realism that theorists had posited in the early to mid-1970s. The rhetoric of the times was, in that sense, so successful in influencing radical film culture that it rendered itself obsolete.

Colin Perry is an art writer and editor. He has written for a number of publications including Art Monthly and Frieze, and is the Reviews Editor of the Moving Image Review & Art Journal.

i http://www.tate.org.uk/about/press-office/press-releases/tate-britain-displays-three-newly-acquired-works-black-audio-film

ii Artists producing documentaries today include Kutlug Ataman, Ursula Biemann, Duncan Campbell, Omer Fast, Luke Fowler, Renzo Martens, Rosalind Nashashibi and Steve McQueen. While the process began around a decade ago with the example of the films programmed for Documenta 11 (2002), the gallery doc-boom is evidently not simply a biennial phenomenon. Artists producing documentaries operate within both a public sphere of biennials and museums, and in the art market, with many contemporary artist-documentary makers being represented by commercial galleries.

iii Another productive term was ‘factography’, an early soviet term used to describe an art concerned with social facts that eschewed bourgeois realism.

iv I would like to thank Laura Mulvey for this insight into the importance of the anti-English sentiment of the New Left.

v Quoted from E.P. Thompson’s ‘The Peculiarities of the English’, The Socialist Register 1965, pp.311-362. Available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/thompson-ep/1965/english.htm#f4

vi For Anderson, much of the trouble lay with the critical model of F.R. Leavis, whose elitist literary criticism was the dominant model in many universities right up to the 1980s, when semiotics, structural and then post-structural accounts leached in. Leavis’s accounts of literature were tightly bound with morality – or ‘moralistic vapouring’ as Nairn would have it – and adhered especially strongly to a tradition of literary realism that would become increasingly problematic for many in the 1970s.

vii In an article from 1970 published in the journal Afterimage, Simon Hartog observed that certain ‘Newsreel’ film-makers were limited because ‘They take the very forms which were used by the established culture changing only the ‘message’ within the form’ (Hartog [1970] in Kidner and Bauer, 2013, p.83).

Bibliography

Anderson, P. (1968) ‘Components of the National Culture’. New Left Review. (50), 3–57.

Demos, T. J. (2013a) Return to the Postcolony. Sternberg Press. Demos, T. J. (2013b) The migrant image: the art and politics of documentary during global crisis. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Dupin, C. (2012) ‘The BFI and film production: half a century of innovative independent film-making’, in Geoffrey Nowell-Smith & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (eds.) The British Film Institute, the Government and Film Culture, 1933-2000. Manchester University Press. pp. 197–218.

Garnham, N. (1972) ‘TV Documentary and Ideology’. Screen. [Online] 13 (2), 109–115.

Johnston, C. & Willemen, P. (1975) ‘Brecht in Britain: The Independent Political Film (on The Nightdeaners)’. Screen. 16 (4), 101–118.

Kidner, D. & Bauer, P. (eds.) (2013) Working Together: Notes on British Film Collectives in the 1970s. Southend on Sea: Focal Point Gallery.

MacCabe, C. (1974) ‘Realism and the Cinema: Notes on some Brechtian theses’. Screen. [Online] 15 (2), 7–27.

Stallabrass, J. (2013) Documentary (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). The MIT Press.

Willemen, P. (1972) ‘On realism in the cinema’. Screen. [Online] 13 (1), 37–44.