The first post by our new Summer 2015 LUX Writer in Residence Federico Windhausen on the pre-history of Argentine Experimental Cinema.

At film festivals and microcinemas, in classrooms and workshops, within universities and academic research groups, across a range of popular and specialized publications, and in a few biographical documentaries, Argentine experimental cinema has received an unprecedented level of recognition.

More specifically, since the late aughts, a small number of filmmakers who were particularly active in the 1970s and early- to mid-1980s, including Narcisa Hirsch and Claudio Caldini, have become the most visible representatives of a previously-neglected tradition of experimental filmmaking within the country. Hirsch, Caldini, and some of their friends and colleagues have even been assigned a name that emphasizes collectivity – the Goethe Group – and indicates their ties to the Goethe Institut in Buenos Aires (an affiliation that was especially strong in the mid- to late-seventies). In subsequent entries I will discuss the work of Hirsch, Caldini, Marielouise Alemann, Horacio Vallereggio, and Jorge Honik, among others, but at the outset here I will ask a question rarely broached within the arenas and forums listed above: What was cine experimental in Latin America before Hirsch, Caldini, and their associates began making films?

One useful way to broach the question is by considering when and where “experimental film” or “experimental cinema” appear as keywords in various hubs of filmmaking activity within Latin America. In Uruguay, for example, the influential film critic Josè Maria Podestà wrote in positive terms in 1952 about the 18th Venice Film Festival’s experimental film section, where the programming of films by Ian Hugo, Len Lye, Curtis Harrington, and James Broughton served as a refutation of the idea that “such film pertains to an antiquated genre and a bygone and finished era.”i More prominently, “experimental cinema” appears in Uruguay’s Festival de Cine Documental y Experimental, initiated in 1954 and now commonly named among the precursors of the New Latin American Cinema. Three years later, across the Río de la Plata, the Asociación Cine Experimental (A.C.E.) in Buenos Aires was formed with subsidies from the Instituto Nacional de Cinematografía and the Fondo Nacional de las Artes, which had recently begun to enact a new policy of supporting Argentine short films economically. That same year, further west on the continent, a 30 year-old filmmaker, Sergio Bravo, helped to found a new film school called Centro de Cine Experimental, which would soon become more formally incorporated into the Universidad de Chile. So do the festivals, associations, and schools aligned with cine experimental in the Southern Cone comprise an institutionally concentrated front line of advocacy, following in the wake of figures such as Podestà?

Not quite. Looking back in 1967, A.C.E. president Enrique Laportilla distanced his organization from subculturally-oriented or overly-specialized cinemas quite clearly, remarking that “the cinema is art and industry” and that “if this is forgotten the cinema transforms itself into a vehicle of enrichment or a minority art.”ii At the Centro de Cine Experimental in Santiago de Chile, one of Bravo’s successors described the school’s approach as “support[ing] national artistic activity with works freed of extra-artistic impositions” while also providing “vocational training.”iii The school’s first screenings of student films in 1959 were declared in the university bulletin to be“experimental and independent cinema,” with the former being defined as “the professional and collective production of films that signify the search for an inherent cinematic language, by way of the development of subjects that express reality.”iv A model filmmaker for the institution was Fernando Birri, who had studied at Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Cinecittà and argued for a “critical realism” grounded in an ethics of filmmaking and a valorization of the under-represented.v Decades later, Bravo would evoke Birri’s rhetoric when explaining that “One cannot express the same thing by holding the camera in hand as by using a crane…It would be immoral to film the everyday life of a Mapuche peasant, for example, by penetrating her house perched on that crane.”vi The notion that the manner in which one makes a film is a moral issue was certainly integral to the tradition of experimental cinema by the early 1960s, although we can pinpoint an ideological parting of the ways at the state-sponsored objective of producing filmmaking “professionals.”

In some ways, cine experimental as institutional label reflected a relatively sweeping utilization of the term that was circulating in North American and European film cultures, especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For Néstor Almendros in 1960, a Cuban experimental cinema could look for inspiration to “the extraordinary precedent of Vertov’s Kino Pravda” and England’s Free Cinema filmmakers.vii For writer Salvador Elizondo, Mexico in 1961 was only in the initial stages of realizing an experimental cinema, as evidenced in films such as Giovanni Korporaal’s El brazo fuerte (1958) and José Báez Esponda’s Carnaval chamula (1959). Elizondo proposed both a quota system and a specialized exhibition circuit for Mexican experimental films, in the hopes that national output would follow after “films of an 100% experimental character” such as Morris Engel’s The Little Fugitive (1953), Francis Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y. (1957), and John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959).viii The terms of this discourse would later be transformed and eclipsed by the New Latin American Cinema, but for my purposes here, signaling its early applications helps to introduce a pre-history of what cine experimental would become by the late 1960s.

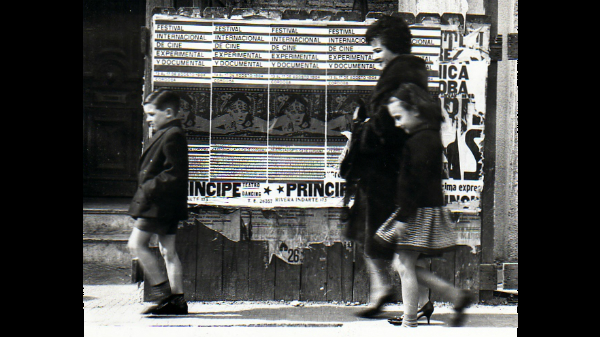

In Argentina (as elsewhere), the circulation of notions of experimental film was facilitated by access to the films themselves. Norman McLaren took his films to the Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar del Plata in 1954 and later served on the jury for the 1964 Festival Internacional de Cine Experimental y Documental in Córdoba. Jonas Mekas attended the Mar del Plata festival in 1962, and Barbara Stone and P. Adams Sitney presented a 45-film, 17-screening survey of the New American Cinema at the Instituto di Tella in Buenos Aires in 1965. One article in the weekly news magazine Confirmado observed that the “eclectic invasion of experimental films” had “scandalized the seasoned audience” at the di Tella, and it offered a rebuttal to the outraged among that “specialized coterie” by pointing out that, for some sociologists, “certain rosy films” (including Disney’s “adolescent stories”) were more “pernicious” than the work of Mekas, Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, and company.ix As if in response to this defense, Primera Plana published in the following month a translation of an article from L’Express on the “experimental cinema of wicked intentions,” which was said to be typified by “the films of Warhol and his friends [who] immerse themselves equally in poetry, drug addiction or homosexuality.”x By 1968, the New American Cinema had been around long enough to undergo a periodization within yet another weekly, Análisis, which identified a split in 1963 between the documentarians and those who aligned themselves with “filmic poetry.”xi Along with the usual suspects named above, the article cited Jack Smith, Ron Rice, and Gregory Markopoulos as members of the latter group, which was said to continue in the tradition of “the cinematic avant-garde of the twenties” and to display “according to some critics…more traditional tendencies than those of the first secessionist group.” Earlier that same year, Análisis had published a middling review of the international competition at EXPRMNTL 4 (Festival international du cinéma expérimental de Knokke-le-Zoute), in which passing reference was made to the jury’s awards having gone to “invalid or insignificant films” (among these, but unnamed in the article, was Michael Snow’s Wavelength).xii

Throughout Latin American film communities of the 1950s and 1960s, the articles, declarations, and institutional publications that took positions on the nature of experimental film did so with varying degrees of definitional clarity and discursive elaboration. Notwithstanding the broadest or vaguest manifestations of the term, however, it is possible to track a specific set of meanings and connotations within Argentine print media by the late 1960s. But I have only taken a few steps in the direction of a historicization of Argentine experimental cinema here. My next entry will discuss not only additional discursive conditions but also some key films.

LUX Writer in Residence Federico Windhausen is a film scholar whose research areas include Latin American cinema (with an emphasis on Argentina) and experimental practices in film, video, and new media. In 2014 he curated the first Oberhausen Seminar, a project by the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, LUX and the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar (New York). Windhausen’s writing has been published in such journals as October, Hitchcock Annual, Grey Room, Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Moving Image, MIRAJ: Moving Image Review & Art Journal, Millennium Film Journal, and Senses of Cinema.

Footnotes

i Josè Maria Podestà, “Cine independiente y experimental en Venecia,”

Cine club 15 (November 1952), p. 1. All quotations in this text are my own translations from Spanish.

ii “Cine experimental: 10 años de labor,”

Análisis 339 (September 11, 1967), p. 36.

iii Quoted in Claudio Salinas Muñoz and Hans Stange,

Historia del Cine Experimental en la Universidad de Chile 1957-1973 (Santiago de Chile: Uqbar, 2008), p. 46.

viJacqueline Mouesca, “Sergio Bravo: pionero del cine documental chileno,”

Araucaria de Chile 37 (1987), p. 101. My translation.

viiNéstor Almendros “Orientaciónes para el cine experimental cubano,”

Lunes de Revolución 59 (April 4, 1960), p. 21.

viii Salvador Elizondo, “Cine experimental,”

Nuevo Cine 3 (August 1961), p. 5.

ix “Adán y Eva, y los jóvenes motociclistas,”

Confirmado (October 13, 1966), pp. 56-7. According to art historian Nicholas Fitch’s doctoral research, the artists who attended the series were especially appreciative of what they saw. I am not assuming that a journalistic report of scandalized audiences is entirely reliable.

x “Cómo dormir en un subterráneo,”

Primera Plana (November 29, 1966), p. 78. The article is a reprint of Otto Hahn, “Andy Warhol, prêtre du cinéma souterrain,”

L’Express (November 14-20, 1966), p. 31.

xi “Evangelistas en Nueva York,”

Análisis 400 (November 13, 1968), pp. 124-27.

xii “Un certamen europeo de cine experimental,”

Análisis 358 (January 22, 1968), p. 32.