One year of particular interest in the History of Moving Image in New Contemporaries is 1968, when Young Contemporaries (as it was then known) invited the Light/Sound Workshop (LSW) to be part of the show.

The Light/Sound Workshop (1965-1968) was based at Hornsey College’s Advanced Studies Group and attracted artists interested in experimenting with light projections, film, animation, tape-slides and sound. Its members (John Bowstead, Tony Rickaby, Dennis Crompton, Peter Cook, Roger Jeffs, Martin Salisbury, Ron Sutherland and others), worked, often collaboratively, on a number of exhibitions and environmental projects like the K4 (Kinetic 4 Dimensional) Festival in Brighton (1967).

For K4 Festival the LSW invited artist Bruce Lacey to show his mechanical constructs in a joint effort to initiate experiments in kinetic/audio/visual environments, with live music from Pink Floyd and the band known as Pyramid. Assisted by staff and students of Hornsey’s Fine Art, Visual Research, Three Dimensional Design, Post Diploma and Film & Television Departments, they eventually came up with the ‘Kinetic Arena’, a white elliptical cyclorama with a lattice girder roof, programmed with continuously developing moving images by 10 high powered automatic projectors, and the ‘Kinetic Labyrinth’, as a space of more enclosed and personal experience.

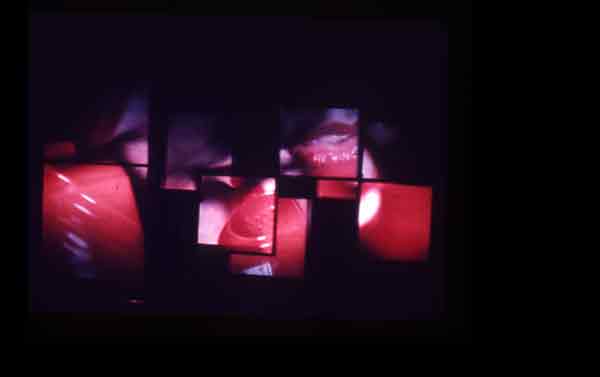

For Young Contemporaries 1968, the LSW showed Time For Change, an ‘automatic projection’ that Tony Rickaby, a member of LSW and later of Archigram, describes as “a series of slide programmes projected from about 12 carousel projectors onto screens hanging in a space which people could walk through”. There was an accompanying soundtrack, although all that now exists are the 35mm slides and some standard-8 film documentation. The pamphlet from the exhibition says:

In just 5 seconds switches 12 changes,

implies a change in role for the artist,

invites 18 screen involvement from the spectator,

with wrap-round sound and phased feedback.

Provides image selection from a rank of 972 stored units,

displays up to 500 images in programmed series,

gives an infinitely variable program potential,

considers an instant happening world with an all round look.

In a recent conversation Rickaby revealed how the whole idea of the LSW came as a reaction to what was at the time considered to be ‘high art’, namely sculpture and painting, and more like an attempt to go against traditional understandings of art altogether. Rickaby argues that there was no specific rationale around the LSW’s subject matter, but in our conversation he referred to Marshall MacLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage, and William S Burrough’s cut -up technique in literature, all coming together as a ‘spin-off’ of Pop Art, advertisements and pop music of the time. Humour was also an important part of LSW’s strategy, as a probe to everyday’s encounters with the urban environment, of “what’s really going on”, all bound up with an intention to create an immediate experience of changing perceptions.

The Light/ Sound Workshop’s story came to grief shortly after this, during the student uprising of May 1968 when Clive Latimer, director of Advanced Studies Group, was dismissed from employment for siding with the students (David Curtis writes about this in his recent History of Artist’s Film and Video in Britain). On 28 May 1968, the Hornsey Student Action Committee occupied the building, initially for 24 hours, but eventually holding out for six weeks in the hope of student representation in the running of the college. They took over day-to-day operations with help from sympathetic lecturers, and produced newsletters and artwork with an overworked Gestetner machine. A planned programme of films and speakers expanded into a critique of all aspects of art education, the social role of art and the politics of design. The Hornsey sit-in had a high media profile – visiting speakers including members of the global alternative utopian scene like Buckminster Fuller as well as controversial psychologist R.D. Laing, finally resulting in the production of more than seventy documents, a Movement for Rethinking Art and Design (MORADE), and an exhibition at the ICA called Hornsey Strikes Again. A national conference on art education was also organised at the Roundhouse, concluding that the Hornsey experiment was “a live laboratory worth any number of textbooks” (Tickner, Lisa ‘Hornsey 1968: The Art School Revolution). From today’s standpoint, where the concept of ‘knowledge production’ has drawn new attention and prompted strong criticism within contemporary art discourse, the Hornsey story can perhaps serve as a paradigm for us to understand such genealogies of conflicts and commitments, in order to follow the transformations that have led to current ‘power-knowledge’ relations in contemporary struggles over education.

A display of materials about the LSW, ‘Young Contemporaries 1968: The Hornsey Light/Sound Workshop’, is now showing at the ICA Reading Room in London in conjunction with the New Contemporaries exhibition, from 23 November 2011 to 15 January 2012. The BFI is currently restoring a number of Bruce Lacey’s films for a BFI Southbank season and DVD release in July 2012, which will coincide with an exhibition of his paintings, assemblages and artifacts at the Camden Arts Centre.