LUX have recently embarked on a project to survey the career of British film artist Malcolm Le Grice. With over 45 years’ work intersecting film, video, performance and music, Le Grice is soon to be the subject of a LUX book, exhibition and DVD.

In 2010 New Zealand Film Archive programmer Mark Williams will be hosting Le Grice in NZ and Australia for a series of screenings and performances. Williams recently spent a month at LUX, compiling a filmography, cataloging Le Grice’s films and getting to know the filmmaker’s body of work. Along the way, Williams kept a journal about the beginnings of Ultimate Le Grice.

Ultimate Le Grice – An archivist for the artist (aka: What I Did On My Holidays)

Day 1 – Ultimate Le Grice

In my first morning at LUX, director Ben Cook lays out the project. Before we can talk about an exhibition or publication, we need to assess the scale of Malcolm’s output.

In 2006 LUX released a DVD of five early Le Grice works. However, this is the tip of the iceberg. As well as creating a large body of work from 1965 to the present, Malcolm has often re-worked his films in their original medium and/or via computer software.

At the London Film-makers Co-op in the 1960s and 70s he was freely able to print and process film, which enabled him to duplicate single channel material for 2, 3 or 4 screens. His discovery of digital technology in the 1980s offered new tools for not only for reproduction and but also interpretation via colour, sound and speed.

While some filmographies exist already, they offer conflicting information about the duration of Malcolm’s work, sometimes the year of production and and do not necessarily include all of the films. So the first part of the project is to make a thorough, coherent filmography.

We also need to know the state of the world’s Malcolm Le Grice collection; there are uncatalogued films at LUX and Malcolm has a body of film and video material at home. We need to assess which works exist only as masters, which need duplicating or repair, and if any are missing.

In a fortnight, I’ll meet the man himself.

Day 2 – Watching the films

I have to admit that I’ve heard more about Malcolm’s work than I’ve seen. The odd film can be found online and I’ve read his book Experimental Film in the Digital Age (Bfi, 2001). While this outlines Malcolm’s critical thoughts about avant-garde film-making, I really need to watch the films. When I do, I see that his politics are matched with some visceral, exciting images.

In Little Dog for Roger (1967) a children and a dog play outside. The original 9.5mm home movie is re-filmed in a contact printer to 16mm. Le Grice has pulled the 9.5mm through the processor so that the edge of the frame and the sprockets are as much the subject as the dog. Meanwhile, the aforementioned mutt races through the centre of the image as if hauling the edge of the 9.5mm film strip into the middle of the 16mm – who’s in charge of this film?

Berlin Horse (1970) is a synergy of sound and image; Brian Eno’s pianola score mimics the looped image of a horse being led from a burning building. The horse is in perpetual motion, an effect complemented by various colour gels and layered copies of the same image.

Weirdly, I have a strange feeling these films are watching me. Exciting stuff.

Image: Malcolm Le Grice, Berlin Horse (1970), still.

Day 3 – The Internet/What is the film?

Today the filmography detective work begins. Firstly I want to see what Malcolm has been screening recently, so I search that most dubious of sources, the internet. It’s not long before I find more questions than answers; For example, Threshold (1972) is listed at anywhere from 10 to 17 minutes in length. There are references to versions made for 1, 2, 3 and 4 screens. Does this mean that each is a different work? This is going to be my first question for Malcolm. Without clarification, this will likely confuse any future researcher or biographer.

Day 4 – The British Film and Video Artists’ Study Collection

Having sifted through the internet, I now turn to more traditional sources. The British Film and Video Artists’ Study Collection is run by David Curtis, a founder of the London Film-makers Co-operative and author of A History of Artists Film and Video in Britain (Bfi, 2006). Besides having over 2,500 titles on video, the Study Collection has 450 artists’ files and a healthy collection of flyers, programme notes and publicity.

The collection is housed at St Martins College of Art and Design. David leads me into a room filled with filing cabinets of ephemera. He points me to three bulging Le Grice files, and several more relating to the Co-op. This is going to be an immersive crash course in British avant-garde cinema. Great! I sit down and open the first folder.

Image: Malcolm Le Grice files at The British Film and Video Artists’ Study Collection.

Day 5/6/7 – Getting to know Le Grice

In the study collection files I thumb my way through many fascinating original documents; programmes, reviews, interviews. It’s interesting to see that the radical activities of the Film Co-op are often covered in the weekly entertainment magazine Time Out.

In a 1972 issue, John du Cane previews a screening of Le Grice films – ‘the films are better understood as events that emerge from his plastic concerns with film process…’

In the same article he discusses Le Grice’s work Reign of the Vampire (1970), noting how live performance and subject matter work together:

‘(Reign of the Vampire) uses six looped sequences, all at different lengths, which are run through the printer in pairs. The sequences are all emotionally charged; soldiers advancing in battle, a porn fuck sequence, a horse running in vicious circles, etc. The meaning of each sequence, and their emotional impact, undergo extensive transformations according to their combinations.’

As well as an insight into Malcolm’s work, the Study Collection reveals the polemics of other Co-op members. Most vociferous is Peter Gidal; ‘People have difficulty with my work because of their narrative sensibility … I don’t want to set up a hierarchical event, where the meaning is complete in any sense. I don’t believe in dominating the viewer but I expect him to work as hard as I work’ (Time Out, Dec 1972)

Image: Malcolm Le Grice, Reign of the Vampire (1970), still.

Day 8 – Dear Malcolm…

After assembling all of the references to Malcolm’s work from the internet and Study Collection files, I now have a 20 page document filled with titles and dates. I suspect some are open to question.

For example, while I know for a fact Malcolm made a film called Reign of the Vampire in 1970, I doubt there is one called Region of the Vampire. What’s more likely is that one typist’s error has spread like a Chinese whisper to other filmographies. However, as I’ve found at least four or five references to ‘Region…’ I note them down as a question for Malcolm.

Among the Study Collection papers I’ve discovered a suggestion of hidden treasure, which gets both sides of my archivist/curators brain buzzing.

In one interview Malcolm makes reference to some ‘lost 8mm films’. Lost? How? Where? He also mentions a printing log book from the Co-op – this could be useful for establishing dates in the filmography. Back at LUX, Ben remembers something about an extended version of the music for Berlin Horse.

These are all exciting things which could form part of a survey exhibition, or be part of a book, detailing the filmmaker’s process. In a day or so I’ll be meeting Malcolm. In advance, I wrote him a question or two…

Dear Malcolm,

Looking forward to meeting you in person – thought I’d come down to Devon on the 9th? I’ve been working through the film/videography. It would be good to run through my questions with you, make corrections, deletions or note the elements that are variable… I found a reference to a log book, that catalogued all your printing and processing at the Co-op. Would you still have this? Also, Ben Cook tells me that somewhere there is an extended version of the music for Berlin Horse..?”

Mark

Day 9 – Dear Mark…

Hi Mark

Good to hear from you in person at last. Re co-op printing log book – yes I have it. Re the Music – I actually think the tape I have from Brian [Eno] is an original … there were 2 alternatives on the tape and a note from him written on the box…

Malcolm

Image: Berlin Horse box with Brian Eno writing.

Day 10 – Meeting the Artist/solving mysteries

In Devon, I meet Malcolm at the station. We drive to his home and get to work.

As I suspect there is no such film as Region of the Vampire. Cue lots of red ink. In some cases Malcolm dismisses references to certain works as completely wrong. Eg: ‘Lucky Pigs was never a four screen film… three screen only’. Cue corrections.

In other cases, he is unsure exactly when some works were made, and faced with the difficulty of trying to recall events of years gone by, possibly not too fussed. ‘It might have been 19…’ For duration he suggests timing the original works stored at LUX.

Malcolm confirms he made a number of 8mm films in the mid-1960s. He now only has China Tea (1965) and sadly suspects the others were stolen or lost. However, he shows me the original slides for his 1968 pieces Wharf and Grass, which haven’t been seen since they were made forty years ago. These need to be copied.

One of the most famous films of the British avant-garde is Malcolm’s Berlin Horse (1970), which he has presented for one, two and four screens, re-cut and screened digitally. I get to ask my archivists question: ‘Does this make them different films?’ Malcolm: ‘No. Different versions of the same piece.’ He draws a parallel with musical improvisation, saying ‘… I question the single authentic work’.

Another red herring for those studying Malcolm’s work – or anybody’s work – is his sense of humour. Whilst poring over documents at the Study Collection, I was sucked in by Malcolm’s 1966 programme notes for Castle 1: ‘This is a short film in close cooperation by Mihima Haas and Doe Nagduk during their recent visit to London… Doe… is mainly responsible for arranging the soundtrack’.

I’m very intrigued. Who were these visiting foreign collaborators? ‘Oh!’ says Malcolm, ‘those names are anagrams for Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. All the soundtrack was done by me’.

Day 11 – The artist’s studio

The next morning we move upstairs to Malcolm’s home studio.

While I’m there we take a look at his cupboard of film material. Sitting on the shelf are titles like Berlin Horse, Whitchurch Down, Academic Still Life. The proximity of Britain’s avant-garde film classics sitting next to a sink is probably nothing to worry about so long as it doesn’t overflow… I make a note to talk to LUX about getting Malcolm’s films into a temperature controlled vault.

Image:

Malcolm sets me up to watch his most recent work. Since the mid-1980s he has shot on video. He edits using the software Premiere Pro. Recent work has sometimes been presented for either 1 and 3 screens, and he has several monitors set up for this purpose. Piles of tapes sit on shelves, as do Beta tape decks. During playback he switches between software, looking for the best colour and contrast.

Image: Malcolm Le Grice in his studio.

Watching the video I search for themes that relate to his early celluloid-based material. It hardly seems realistic to expect an artist to still be dealing with the same ideas forty-something years after his first work. And certainly his artistic drive seems to have shifted, at least in part, from the confrontational to the reflective.

An early work like Castle 2 (1967) used images of military machinery and loops of a woman suggesting endless goal-setting in the workplace. It played havoc with our expectations of cinematic structure, putting the title and Le Grice’s name in the middle of the film. To me the most resonant of the recent works are those associated with the death of his father, Even the Cyclops Pays the Ferryman (1998) and Chronos Fragmented (1995).

Day 12 Punch the clock

Returning to LUX, I have answers to some questions about Malcolm’s work, but not all. But now that we have established contact we can solve a few mysteries via email. Those issues we’re hazy on (eg: was x work ever made for x screens..?) we can corroborate with evidence from the files of the Study Collection.

In terms of duration, I decide Malcolm is right. The only reliable measure is to time everything with a stopwatch.

As soon as I begin, I realize that practically EVERY noted duration of a Malcolm Le Grice film in a programme, flyer or filmography is 100% wrong. There are differences of up to 5 minutes. Threshold, commonly noted as 17 minutes, is 13.30. Berlin Horse which appears in most filmographies at 8-9 minutes is 6 mins 30 seconds.

These are important differences. Why? Because the actual time says something about the artist’s craft and thought. Why, for example did the film maker make the work 45 seconds as opposed to a nice, round 1 minute?

Day 13/14 – Ultimate Le Grice is underway…

Provoked by my questions, and thinking of exhibition possibilities, Malcolm has set about excavating his cupboard at home, and seeing what’s in his possession.

Likewise, I go through LUX’s collection of uncatalogued Le Grice works and enter 60 items into the Lux database. I send a copy to Malcolm, who is thrilled.

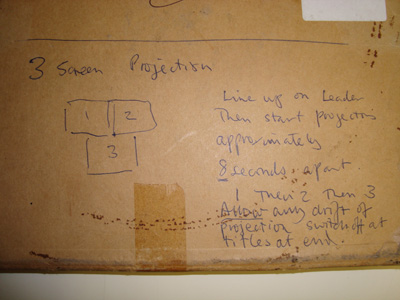

Some of the cans have instructions written on them by Malcolm for how to present the works. I’m amazed – beyond Malcolm’s presence, these are the only instructions that exist for these works. I photocopy them and ask Malcolm to consider writing a formal set of directions for presenting each of his performance works.

Image: Instructions for presentation of Threshold.

In terms of establishing the ground work for this project it feels like the wheels are in motion. The filmography will go forward on the premise of going back to basics. LUX have a complete catalogue of all their Le Grice holdings. Malcolm is working through his own collection of film material. Even more exciting, he has even begun assembling digital versions of Wharf and Grass based on the original 1968 slides.

Ultimate Le Grice is underway.

Mark Williams is Exhibition Projects Developer at the New Zealand Film Archive.