To celebrate the publication of their new book Margaret Tait, Poems, Stories and Writings, Carcanet Press have kindly agree to us reprinting this brilliant short description by Margaret Tait of the founding of her DIY film festival on Rose Street, Edinburgh in the 1950s, a great inspiration for our own festival starting later this month…

Festivals, in the sense in which the word is used in this century, are all advertisements of something or other, — of the place where they take place, of the products of exhibitors, performers and decorators. The Edinburgh International Festival of Music and Drama is a tourist draw for Edinburgh, and for performers a showground for their talent. This ready-made showground is utilised by the Edinburgh Film Festival and by numerous independent theatrical companies who have works to present to the receptive public, — because the one thing that is exceptional about the Edinburgh Festival is the public. The operas, the plays, the musical pieces performed might occur in any average week in London or New York. Not so the public. For the city is crammed full for three weeks with people who have come from far away with just one idea of seeing as many shows as possible. And for those three weeks in the year all the citizens of Edinburgh too become art-lovers, opera-mad, crazy about theatre, music and film.

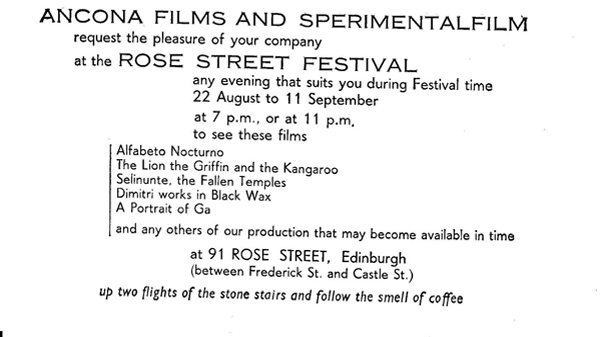

I had films to show, produced by myself and the two groups I work with, Ancona Films and Sperimental Film, and a place to show them in, in Edinburgh, so I decided to use this festival time of public receptivity to show our wares. In my workrooms in Rose Street, Edinburgh I fitted out a small theatre. The biggest room has a reasonable length of throw for the projector and very nice acoustics for sound reproduction. A couple of small windows daringly made in an intervening wall turned a neighbouring small room into a projection booth. Ingenious if slightly confusing manipulation of switches and leads by a colleague gave me adequate control of theatre lights etc. from a central point. My New York partner, Peter Hollander, designed us an excellent poster, I had invitation cards printed, and advertised as well as I could the coming ‘Rose Street Film Festival’.

I checked with the Police that there was no objection to my holding such a show provided I didn’t charge for admission. At the last minute the rain started coming through the roof of our condemned premises, but even that was righted after one uncomplaining audience had got a minor wetting. The shows were at 7 p.m. and at 11 p.m each evening. 11 p.m. was for people who had been to some other show in town but weren’t yet ready to call it a day, and it proved to be popular. As people came up our narrow stairs they usually wondered, ‘Is this the right place?’ When they were asked into our reception room and given a cup of coffee they wondered all the more. Sometimes when there were not very many in the audience they looked very doubtful indeed. – Have we come to the right place? But those doubtful faces underwent a remarkable and gratifying change of expression during the performance, and when I met the visitors in the theatre after the show they were usually very happy to stay on awhile and talk about films and other things and drink Italian coffee.

The programme was as follows.

ALFABETO NOTTURNO made by Agostino and Alfonso Sansone, Fernando Birri and Peter Hollander in Sicily in 1952, an account of evening school in the tiny mountain village of Torretta in the heart of Giuliana country.

THE LION THE GRIFFIN AND THE KANGAROO made by Peter Hollander and Margaret Tait in 1951-52, a film sponsored by the city of Perugia and the Italian University for Foreigners, by U.S.I.S. and the Fulbright Commission, about the mediaeval and once warlike city which now is a meeting place for foreign students. SELINUNTE, THE FALLEN TEMPLES, made by Fernando Birri in 1951, a study of the Greek ruins at Selinunte in southern Sicily.

DIMITRI WORKS IN BLACK WAX made by Peter Hollander in Rome in 1952, an account of the lost wax method of casting and a study of the sculptor, Dimitri Hadzi.

A PORTRAIT OF GA a colour portrait of an old lady, made by Margaret Tait in 1952-53.

Projection was all on 16mm., and in fact all of the films except ‘Selinunte’ were produced on 16mm. Since 1952 SperimentalFilm have produced ‘Centrale Termo-Elettrica’ and ‘Immagini Popolari Siciliane’ but were unable to send 16mm. copies of those. In the second week of the festival I received from New York Ancona Films’ two most recent productions, SOMETIMES A NEWSPAPER, made by Peter Hollander in 1953-54 and SHAPES, a colour film for children made by Peter Hollander, Miriam Schlein and Hermann Gottesmann in 1954. We aim to make films neither for the specialist nor for the hypothetical moronic ‘mass’ but for the intelligent general public. Personally I disagree with all attempts to ‘raise the level of public taste’. I think we have our work cut out satisfying the demand for entertainment at a high level that already exists. Since our films are mostly on 16mm. they usually get shown to specialised audiences, and I had had no opportunity of judging their impact on a general audience.

Rose Street is known as rather a tough street, and I was afraid our films would not appeal to the local inhabitants, and rather hoped they wouldn’t come up. After the festival had been going on for about a week they suddenly noticed it and I had a visit first of all from three or four small children from the street who sat quietly through the performance and declared that they had enjoyed it. Then the Rose Street children began to accost me daily in the street with ‘Is there films tonight, missis?’ and for a day or two gangs of them came to the seven o’clock performance. But they got a bit noisy and disturbed the rest of the audience, so I had to keep the children out of the evening shows, promising them a show for themselves later on. The first time that I was saying at the street door, ‘No, I’m sorry, no children in the evenings’ a couple of teenage boys who habitually stand in the doorway opposite dressed in the current ‘teddy-boy’ fashion (popularly and rather ingenuously supposed to be favoured by delinquents only) strode across and entered, to show the children how grownup they were I suppose. At that performance, as luck would have it, an amplifier valve blew, but the boys didn’t want to leave. I guess they preferred not to face the children in the street, who would no doubt infer that they had been turned out, so I showed them the whole programme silent. They came back the next evening and saw it again, with sound. They returned a third evening with other two young boys. There were other people too who came to see the films several times, and I made some new friends this way.

Many people came to the Rose Street Festival after a concert in the Usher Hall or after the opera, and they certainly added a festival ‘atmosphere’. Some of the most appreciative members of our audiences were practising artists in other fields – architects, musicians, a few painters, one poet. It was very encouraging for me to get so much appreciation from the very people I would like to like the films, — direct people, genuine people, and it was a great joy that most of my visitors were like that. There were only very few who had the upside-down sophisticated state of mind which I associate with a certain type of suburban film society member, hack reporters, and the sort of smart alec who must always be in the know and in the fashion. Those upside-down people were the only ones who didn’t care for our films. They said they were ‘hoping for something more experimental’ or ‘WHY did I make these films?’ as if they couldn’t understand anyone going to any trouble to make a film that is quite lucid. Those people puzzle me because they all know about films, they probably can reel off a list of all Chaplin’s films and do appreciate the recognised classics and enjoy anything securely labelled ‘experimental’ (and therefore probably already some years out of date as an experiment), and I dare say their opinion is of some sort of importance in a way. But it is not important to me in my work, and I don’t want to make films for them because the things they want always seem to me in some way phoney. It is as if they had difficulty in understanding anything straightforward and clear.

Ancona Films and Sperimentalfilm productions are straightforward. Most of them do contain experimental work, but just some experiment of our own. Each of our films has been made about a subject we consider interesting in itself, and it was very nice that in the discussions which our audiences carried on it was the subject of the film that they discussed rather than the film as film. The technique of the lost wax method of casting was entered into, the direct method of language teaching, the problem of illiteracy in remote Sicilian villages, the nature of the stone in Selinunte and Perugia, and so on. Audiences were small and so the talk was very direct and informal.

I was particularly pleased by the response of Edinburgh people. I found a very keen positive interest in films and enthusiasm for the idea of more films being produced in Scotland, especially by Scottish independents. Of course there must always have been a positive feeling for film in Edinburgh for the Film Guild to have been formed in the first place and to have grown into the Edinburgh Film Festival. This latter has become very much of a ‘festival proper’. Rose Street as a street has a reputation for being improper, and although the Rose Street Film Festival is in no danger of becoming improper, I intend to keep it unofficial and individual.

Margaret Tait, December 1954