The feminist critique of Stan Brakhage’s films is usually associated with the rise of Women’s Liberation in the US in the late 1960s when female audience members often asked the filmmaker difficult questions about the gender politics of his work, and filmmakers such as Barbara Hammer and Marjorie Keller reworked key aspects of his work from a feminist perspective.

However a critique of the patriarchal worldview of Brakhage’s work was already in place in the late 1950s, in the dialogue he had with the artist Carolee Schneemann, who was a frequent correspondent and important critic. Schneemann and Brakhage were key figures in one another’s development as artists. The struggle between them however, and the inequity in their relationship can be clearly seen in the differing accounts they offer of the filming of Cat’s Cradle in 1958 – a crucial work in Brakhage’s establishment of a domestic cinema, which Schneemann could only privately critique for the way in which it undermined her own efforts to build a world within her home that defied the contemporary culture of containment.

Although it was edited in 1959, the footage for Cat’s Cradle was taken the previous year. Shortly after their marriage Stan and Jane Brakhage travelled across the country, to South Shaftsbury, near Bennington in Vermont, in order to pay a two-week visit to Stan’s high school friend, the composer James Tenney and his wife the artist Carolee Schneemann. Cat’s Cradle records their meeting at the beginning of Jane’s pregnancy. Brakhage recounted to P. Adams Sitney his reasons for their travel to Vermont:

Jane […] had an image of what marriage was, which was uninteresting for her. I had a concept of what marriage was that was struck off the marriage of […] James Tenney and Carolee Schneemann [….] Fool that I was, like many young husbands are, I felt an urgency to take Jane into a relationship with them, that is, went to visit them in Vermont for two very disturbing weeks with them, where naturally Jane, not sharing my mythos of marriage, and certainly not by way of another man and woman, resisted all of that concept tremendously.(1)

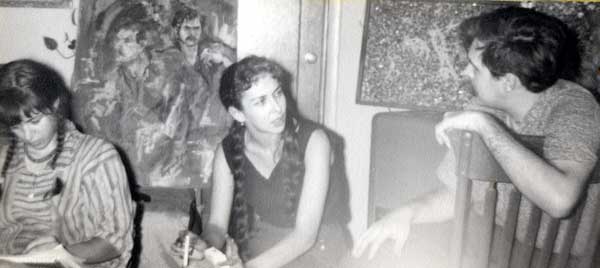

Schneemann’s recollection of the visit is similar, writing a memorial in the first person to Brakhage she notes, ‘as hosts and guests, we struggled over who empties overflowing ashtrays? How do we share? Who shops? Cooks? Washes up?’(2) During this period of time Schneemann produced paintings of both Jane and Stan Brakhage. Jane is depicted seated nude, her pregnant belly just beginning to show. This painting was itself a cause of anxiety during the stay, Schneemann recounted in a letter to a friend:

THE PAINTING was started immediately with strugglings worse than ever – head over and over again from fine stretch of tensed body – sitting up, queenly exposed for me […] She was pleased and disconcerted; “the mood” was strong but “that poor animal looks so trapped,” (my heart caving footward tense). Not at all, I said, it is all open, the figure is tensed to move, to rise, it is free… “no,” she said, “that is the difference between us, I would let the animal out of the trap, but you wouldn’t.”(3)

Schneemann had intended the painting as a wedding gift, but on seeing the couple’s reaction to it decided to keep it. In the other portrait, which was later hung in the couple’s home, Stan is shown to the shoulders only. His face is twice on a single head, it is Janus faced, a pun on the couple’s new partnership, Jane – us.(4)

Cats Cradle is set entirely within the interior spaces of Schneemann and Tenney’s home. It is a remarkably short film, a mere five minutes, yet it packs in almost seven hundred shots – at times it feels as if the mark left by the splicing tape at the top of the frame is a permanent addition, while the rapidity of montage occasionally approaches the intensity of a flicker. The film begins and ends in a bedroom occupied by Stan and Jane, the textures of this room are minutely observed – the patterns of the bold chintz wallpaper moves in and out of focus. The camera frames an overflowing ashtray and a cat moving in amongst the bedspread; light is reflected formlessly across fur. Sunlight is dimly filtered through coloured curtains or emerges in bright shafts through cracks within them, emphasising a sense of interior space. This light undulates as it passes through the moving trees beyond the window; diverse surfaces – including the wallpaper, a bedspread and a cardboard box – become makeshift screens for the projection of this dance of sunshine. Jane and Stan, in separate shots, move beyond this room through a doorframe, mirroring some of the framing effects used in the earlier film Wedlock House.

Before long Schneemann and Tenney are introduced, the former is at an easel, the latter by a record player – the respective tools of their trade. Each of the four are presented in static shots presenting individual vignettes, inter-cut with frames of the cat’s fur, which flash between them. The rhythm of these shots increases in pace, occasionally the frame is turned upside down. Schneemann is shown carrying dishes, Tenney at a desk, Jane smiling, Stan smoking. The camera returns to the bedroom where Jane disrobes. The image fades to black and Stan’s signature appears inscribed into black leader.

The effect of framing each of the protagonists separately in each of the hundreds of shots that make up the film is an atmosphere of separation and containment. Each individual is contained within the frame as if each occupying a separate room within the house. Brakhage compartmentalises the home in highly conventional ways in the film – assigning the spaces for gendered forms of activity, which come together in the sensuously depicted space of the bedroom. Schneemann is clearly figured as the homemaker, active within the home among the static faces of the Brakhages and Tenney. Schneemann recognised the separation of individuals that Brakhge was creating even while the work was still being shot. At the time of the guests’ departure Schneemann wrote to her friend, the writer Naomi Nevinson,

THE FILM was mainly done in the guest room with M.J. [Mary Jane Brakhage] and then a lot of Jim writing music and the kitchen, using me as I peeled onions in an apron. And my sense of being superfluous, of his wanting to put me down […] No, not really put me down, but rather aside. The last feet of film he took with strange unmeaning as I was painting M.J. in the studio and he wanted me to be painting in the apron! […] why have a woman’s hands do other than draw the needle through the cloth and peel the onion when the alter-ego man writes music? (5)

Schneemann would never forget the apron, forty-five years after the shooting of the film she recalled bitterly, ‘you insisted I wear the silly apron Jim’s mother had sent for Christmas.’(6) The apron is the subject of a shot that pulls in and out of focus on its pattern, a curlicued navy toile de joie. The pattern rhymes visually with that of the curtains that frame Schneemann’s first appearance in the film. She becomes then part of the house itself, inextricable from the domestic, even her own artistic work being equated with that of the kitchen.

In a letter that Schneemann sent to Levinson a year after the visit and following a recent row with both Stan and Jane Brakhage, she describes Tenney’s reaction to the making of the film, remembering,

Jim saying to Stan that we felt he was conscientiously willing something hideous out of our lives and using the house for this and his supercilious reply to me: “You did the décor didn’t you.” “Décor” from those handed out, found and lost objects, out of our joy at making do with chance things, and the colors and spaces which we love now of that house as we did then; a marvellous inner landscape for love. (Which Stan the fantastic hypocrite revered and stayed in for two months the year before).(7)

Schneemann and Tenney very clearly understood the decoration of the interior of their home as a reflection on their relationship with one another. This relationship, as Brakhage recognised, was highly sexually progressive (the complex boundaries of their marriage are negotiated throughout Schneemann’s published letters from the late 1950s) and attempted to reconsider deeply ingrained gender norms. What Brakhage does to this home in the film abrades the idea of marriage Schneemann and Tenney had developed.

This idea of the ‘proper’ use of the spaces of the home would be critiqued early in the next decade by Schneemann’s best-known film Fuses (1964-1967), which sees every domestic space as teeming with erotic potential and offers a counternarrative to Brakhage’s cinema of the home.

(1) P. Adams Sitney ‘Interview with Stan Brakhage’ (1963) reprinted in Sitney (ed.), The Film Culture Reader, (New York: First Cooper Square Press, 2000), p. 207.

(2) Carolee Schneemann, ‘It is Painting,’ in David E. James ed. Stan Brakhage: Filmmaker (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), p.81.

(3) Letter from CS to Naomi Levinson dated 28 May 1958, reprinted in Kristine Stiles (ed.), Correspondence Course: An Epistolary History of Carolee Schneemann and her Circle, (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 28.

(4) Jane Wodening pointed out the pun to me in conversation, Stapleton, Colorado, August 2007.

(5) Letter from CS to Naomi Levinson dated 28 May 1958, reprinted in Stiles (ed.), Correspondence Course, p. 28.

(6) Schneemann, ‘It is Painting,’ p. 81.

(7) CS to Naomi Levinson dated 29 May 1959 in Stiles (ed.), Correspondence Course, p. 38.

James Boaden is a lecturer in the history of art at the University of York. He is currently working on a book about the circle of Stan Brakhage from 1950-1965. He has curated film screenings at BFI Southbank, Tate Modern, and La Virreina, Barcelona and has published essays in Art History, Oxford Art Journal, and Little Joe.