Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen is characterised by its sense of reflexivity, which this year manifested itself particularly clearly in its programme of discursive events, Podium, and in some of the work presented. Yet whilst some of that work was self-reflexive in the manner of the postmodern bricoleur – the posturing of the cultural anthropologist-cum-filmmaker – the festival’s own soul-searching is entirely earnest; a welcome (and indeed, specifically Germanic) sense of understated yet rigorous investigation. With 2011 marking its 57th edition, it has had the time to gorge itself on the fruits of its own success, to become bloated, vain and sentimental or archly self-referential and cryptic, but it has refused to do so, retaining an admirably open structure and a generosity of spirit which ensures that not only the work shown is respected, but the sense of encounter carefully nurtured.

Podium this year looked at the interface of industry and art, posing provocative questions about the marketplace and the moving image to panels of nominally polarised speakers from the art world. In Cheap and Cheerful — Creative Industry or Cultural Exploitation?, economist Arjo Klamers (Erasmus University, Rotterdam) argued that we are moving away from an economy based on commodities to one based on imagination, on ethereal concepts, and that it is therefore difficult to attribute value to work which, in a post-industrial landscape, deals with intangibles such as ideas. Artists’ interaction with the ‘societal sphere’, in his economic model, is drawn from their relationships with peers and ‘family’, in their oikos (family) sphere, and less so the market.

Klamers’ analysis was predicated on a transition from one economic state to another, but it seems altogether more likely that, rather than moving away from commodities to ideas, imagination has been co-opted and forced to industrialise: the New Labour construction ‘creative industry’ surely points to the commodification of ideas. Moderator Steven ten Thije (Research Curator, University of Hildesheim) went on to position the term in terms of the implicit contract it implies with the machine; with the notion of productivity taking place via the machine exclusively.

With an adversarial tone, Chris Dercon (Tate Modern) and Charles Esche (Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven) united, ostensibly, to attempt to refute Klamers’ argument. Where Dercon seized on the preponderance of family metaphors in Klamers’ model, Esche was more directly combative, countering that the problem of artists’ work having no perceivable value is precisely because capitalism allows it to be so. Esche’s Marxist stance, which refuted power structures, and Dercon’s “sneaky” strategy to work to influence those structures, effectively merged to assert that what was needed, in Esche’s words, was to “organise”: Dercon by forming ‘teams’ rather than Klamers’ more homespun ‘family’, and Esche by something which approached unionisation; a “global demos.”

Both agreed that their institutions could and should do more to interact with alternative spaces and modes of production, admirably, according to Charles Esche, to “the point of [their] own abolition” — but whilst enjoyably polemical in approach, what either curator failed to acknowledge was the extent to which their interaction with the locus of power – with the marketplace – implicated them. If this seemed rather disingenuous, it at least signalled a lack of self-awareness, a thesis perhaps borne out by the sledgehammer irony of an event entitled No Soul For Sale (2010) in an institution part-financed by BP.

The bold interrogative of How Alternative Are Alternative Spaces? quickly answered itself: some alternative spaces are more alternative than others. Thomas Peutz’ introduction to SMART Project Space (Amsterdam) provoked the realisation that the cachet afforded by the ‘alternative’ designation should have a best-before date. Where it had been established as an alternative to the city’s Stedelijk Museum, it now functions entirely within the conventional museo-gallery sphere, as Peutz’ slideshow of grant-funded, slick and expensive shows, high-profile live events, architect-porn interiors, a “good restaurant” indicated. Not that ‘alternative’ has to function as a synonym for ‘grungy’, of course, but in the context of SMART, Thomas Beard and Ed Halter’s relatively young Brooklyn space, Light Industry, seemed entirely more worthy of the title, and this does in part stem from its low-key, lo-fi existence.

What escaped discussion but should have been identified at the outset is that the most alternative space must logically be one which isn’t a space at all, or at least is as dissimilar to a ‘regular’ space as possible; which radically deconstructs the idea of (the) space. And on this level, Light Industry has remarkable integrity. Thomas Beard and Ed Halter, who established it in 2008, explained that they intended to exhibit work in the context in which artists had originally intended — which, for many, particularly those working in 16mm or 8mm film, meant an intimate cinema space with a small screen, rather than a monumental wall-sized gallery installation with a transient audience, however spectacular its appeal. Beard and Halter sidestepped the (faulty) argument of the ‘alternative’ necessitating the ‘new’ by acknowledging New York’s rich history of alternative spaces, offering that Light Industry is a part of that lineage; of the ‘ecology’ of the city’s artistic community. Despite a necessarily partisan view on the business practices of more mainstream art institutions, they adroitly defused any call for militancy, arguing, as Beard offered, “’alternative’ is not the same as ‘oppositional’.”

All the same, Light Industry’s very existence is a challenge to large institutional spaces, working as it does with many of the same artists, and offering them fees, which even monoliths such as MoMa don’t see fit to do. “We do wonder what [institutions] are doing,” Halter remarked. “We’re presenting work every week on minuscule budgets and paying artists.” Light Industry is subverting and challenging the status quo, at least in New York, and its physical constitution is instrumental to enabling it to continue to do this — ironically, precisely because it hasn’t the money or the premises, the funding or the patrons of the institutions. In an environment in which even ‘alternative’ spaces aspire to the bureaucracy of their sometime institutional adversaries, it is Light Industry’s status as a provisional space (Halter and Beard are about to move to their third address in as many years) with a lightweight and equally provisional organisational structure, which mark it as ‘other’. And in this way, it suggests that to occupy a temporary (autonomous) zone, a place of shifting boundaries, is to most effectively challenge the hegemony.

Elsewhere in the festival, the work of filmmakers Grzegorz Królikiewicz and William E. Jones was featured in several monograph programmes, which, for the latter, meant a series of curated screenings, William E. Jones Presents, which positioned his own films in a contrapuntal relationship with historical works by other filmmakers. With a schedule that surveyed 1970s gay porn (or perhaps the rather more coy ‘sex films’ as aestheticised by curators) alongside work which had either inspired his own, or with which he felt an affinity, Jones’ selection established a reflexive arena which enlivened the often-flat dynamics of solo screenings.

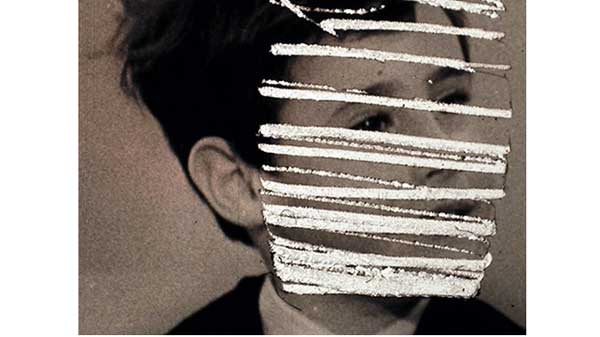

In two new works not listed in the original programme notes, Jones exhumes archival material, often from the Library of Congress. Travelling across and through images via an intriguing technique which referenced the uneasy transitions produced by photo programs such as iPhoto, their borders, written titles and grain, otherwise unnoticeable details assumed a significance which subordinated the subjects themselves: an hypnotic device, formally, reminiscent of Ken Jacobs’ or Fred Worden’s interrogations of the image. In “Killed” (2009), the archivist’s excised circle, a hole punched through the centre of images deemed sensitive, offensive or just not good enough, becomes a cataract, a void, at once attesting to the physicality or indexicality of the image and at the same time monstrous; preserving above all else the blunt and indiscriminate act of the censor. The notion of obliteration or erasure, and its effect on the dynamics of the image, persists in Jones’ other works (Aggressive Child, 2010), and in a rather generous act of raising the magician’s curtain, Ivan Ladislav Galeta’s Water Pulu 1869 1896 (1987) and Wallace Berman’s Aleph (1956-66) together provide historical antecedents, to a large extent, for Jones’ process.

But reflexivity invariably gave way to self-reflexivity, and perhaps most baldly in the final programme of the series which includes, among work by George Landow / Owen Land, Ernst Schmidt Jr. and Chris Langdon, a 35 minute compilation of some of Jones’ films in a ‘Greatest Hits’ vein, entitled Chiseled and Compiled, Remixed (2011). This might have been unobjectionable, useful even, if it packaged work otherwise unseen at Oberhausen, but as it was, it simply re-presented excerpts of films which had played the night before. And it’s this somewhat brazen auto-recontextualisation, to give it an entirely awkward name, which coloured his more recent practice at a more general level, suggesting that much of Jones’ new work might only be made meaningful by existing at a remove from itself, in a hall of mirrors; that it might mythologise itself via a process of distanciation. Such a strategy is doubtless valid in terms of conceptual practice, but Jones’ process, in his more recent works, also tended to occlude his message. It’s a shame his earlier works – Massillon (1991) and Mansfield 1962 (2006) or Tearoom (1962/2007) for instance – didn’t screen, as they feel entirely more substantial.

The festival at Oberhausen, though, is more than the sum of its parts. It recognises that a film festival is about the encounter as much as the work itself, and engineering that encounter – and, crucially, affording it the freedom to go where it may – is perhaps both its greatest success and its most enduring function. It requires humility and generosity to allow these manifold representations to exist: to relinquish control, in part, and acknowledge that the heart of the festival is sustained by chaos – the unpredictable synthesis created by its attendees – as much as structure. As much as the ‘alternative spaces’ dissected in the Podium sessions, it is via creating a temporary zone for dialogue, exchange, reflection, that festivals such as that in Oberhausen ensure a currency beyond dominant cultural modes, and crucially beyond the marketplace of the art fair or gallery or institution. Indeed, given that its structure is provisional in both time and space, its capacity to create alternatives is even broader than those alternative spaces. The statelessness of festivals, the ability to allow for uncertainty, is their strength, and Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen acknowledges and develops this remarkably effectively.

Adam Pugh