Historically, American avant-garde cinema has overwhelmingly adopted a rental model of distribution: filmmakers deposit prints with an agency such as Canyon Cinema or Film-makers’ Cooperative, which rents them for a per screening fee.

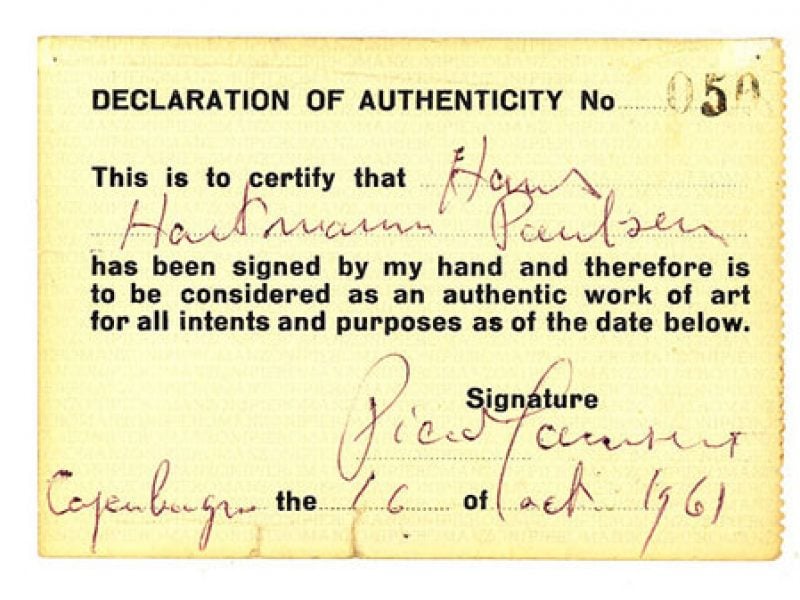

Today, a number of alternatives are displacing the co-op model from the hegemonic position it has occupied since the mid-twentieth century: the sale of films as collectible art objects in the form of the limited edition, the sale of uneditioned mass market DVDs, and the often unauthorized digital distribution of films through file-sharing sites and other online outlets. Though adopting very different attitudes towards scarcity and authenticity, all these increasingly prevalent models of distribution share a conception of the moving image as something that can be owned rather than simply experienced throughout the duration of an ephemeral projection.

Possessable cinema is newly ubiquitous, but not new. From the vantage point of the multiple and competing models of ownership that have emerged since the VHS tape, it is worth taking a look back at a somewhat marginal but fascinating initiative to offer viewers the opportunity to own avant-garde cinema and view it privately at home, on 8mm reduction prints. In the late 1960s, Stan Brakhage entered into a partnership with the Evergreen Book Club, an imprint of Barney Rosset’s Grove Press, to offer unsigned and unnumbered prints of his Window Water Baby Moving (1959) and one portion of Lovemaking (1968) for sale to club subscribers. Lovemaking was a thirty-six-minute film in four parts: heterosexual sex, copulation between dogs, homosexual sex, and emerging childhood sexuality; the Evergreen Club release excerpted only the first. In June 1967, Brakhage wrote to Grove’s film division,

I care more about 8mm than all the other mms put together: I want, have wanted for years, to get works of art in film INTO THE HOME, like LP records, poetry books, etcetera – that is: in the sense of having films available to anyone’s sensibility for viewing over and over again – that is: for by-passing the theatrical occasion (and all its limitations of filmmart/filmview) ALTOGETHER. I mean I didn’t/don’t care about theatrical distribution onedamnbitwhatsoever: BUT the very mention of sale of prints to homes in 8mm, etc., DOES make my heart go pittypat, my eyes to sparkle red and green and blue ball and falling-water/shooting-stars.

Above all, the promise of 8mm distribution was the promise of intimate access and enduring engagement. Brakhage’s desire to overcome the one-time-only limitations of theatrical exhibition chimes with that of Bruce Conner, who wrote on his 1963 Ford Foundation application that he “consider[s] film distribution, as it is now, to be antagonistic to artistic process.” Conner believed that his films were best suited to repeat viewings in a domestic setting, so that the viewer might discover something new each time. But whereas Conner compared the collection of films to that of prints and paintings, Brakhage chose to pursue the mass distribution model of publishing. He hoped that Grove, which had become involved in the film business after purchasing the holdings of Cinema 16 in 1967, would create a market for 8mm sales that would “the BIGGEST thing in art mark since LPs.”

In addition to providing filmmakers with a way of pursuing mass access, the sale of 8mm reduction prints also offered a financial opportunity. Window Water Baby Moving sold 540 copies priced at twenty dollars each between 1 July 1968 and 30 June 1970, netting Brakhage $583.50 in royalties. Sales of Lovemaking, meanwhile, fared significantly better, no doubt in part thanks to the titillating advertisements that appeared in Evergreen Club News. Advertisements for the film regularly appeared with nude photos, next to a film called Psychomontage (1963) by the doctors Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen. According to the ad, the Kronhausens were best known for their books Pornography and the Law and The Sexually Responsive Woman. In the same two-year period, Grove sold 6669 copies of Lovemaking at the members’ price of twenty dollars, providing Brakhage with a profit of $7516 – a buying power of about $44,809 in 2012 dollars, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI inflation calculator.

The relative financial success of Lovemaking is closely tied to the marketing of the film as experimental pornography, ideal for the kind of private home viewing that 8mm could afford. The twenty-dollar price tag (thirty for non-members) was extremely high compared to other erotic films available for mail order in this period. To give some sense of comparison, film scholar Eric Schaefer has noted that a December 1960 issue of Chicks and Chuckles advertised 8mm films priced from $0.80 (when purchased in bulk) to three dollars. The Evergreen Club News, however, was catering to a specialized audience. When Rosset launched the Club, he ran a series of advertisements in papers like the Village Voice that foregrounded attachments at once erotic and countercultural, with headlines like “Dear Sir, I Swear I’m Over 21,” “For Adults Only,” and “Join the Underground!”

Though it was still possible to face federal criminal charges for using the mail to carry obscene materials, Schafer notes that in 1959 postmaster general Arthur E. Summerfield announced that mail-order pornography generated $500 million a year in revenue. The Evergreen Book Club constituted a high-brow niche of this lucrative industry, offering smut and culture at once: Pauline Réage’s Story of O alongside Franz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, and a triple LP version of the Marquis de Sade’s Justine alongside pulp paperbacks with titles like Young Girls and Their Older Teachers and First-Time Swappers. In this context, Lovemaking was marketed not by touting Brakhage’s celebrity within avant-garde cinema circles, but by its tasteful yet explicit nature: “Daring and honest in its approach, the film makes art of a realm once reserved for forbidden films.” In addition to being sold as a stand-alone film, the Evergreen version of Lovemaking was a part of the compilation Erotic Celebration 1, which included titles such as Naughty Nurse and Everready.

Bruce Conner had a very different experience with his attempt to sell 8mm prints. In early 1968, he wrote in the Canyon Cinemanews that he had been trying to sell 8mm films for the previous three years, but that despite distributing them to multiple locations, “there [were] very few respondents to the bait.” Nonetheless, he published a list of thirteen customers and their addresses, so that other filmmakers might contact them, adding – in what might be a dig at Brakhage’s success, but which in any case points to the close ties between 8mm home sales and pornography – that the list was provided “assuming that these people do not just want to see dirty movies.” He also details the costs of making reduction prints and buying reels and boxes for them. The note reads as something of a how-to guide. Indeed, a few months later the Cinemanews included a call for makers and collectors of “HOME LIBRARY PRINTS in 8mm.” The initiative, however, met with little success. By 1981, Cinemanews’ special issue on super 8mm would feature no references on the idea of it being a medium that might make film collectible like books or records, save for a short, melancholic letter from Conner: “For some time I offered prints of these movies for sale through Canyon Coop. It finally become clear that there wasn’t much market for the films and I couldn’t invent it all by myself… I seldom look at 8mm films now… The attitudes towards 8mm film and the intimate space of this image that I have discussed in this letter are past reminiscences and are becoming darker. I haven’t made any 8mm films since 1968.”

Conner’s experience is much more representative of the viability of 8mm home sales than Brakhage’s. The initiative to sell avant-garde films to home viewers never took hold in any widespread way. Even the mass access of Lovemaking was to be short lived. The 8mm prints have long been unavailable, though occasionally one turns up on eBay or at specialized bookstores, such as New York’s Specific Object. Brakhage pulled the 36-minute version of the film from distribution in 1982 following the United States Supreme Court decision New York v. Ferber, which ruled that child pornography was not protected under the First Amendment right to free speech. In a letter to Grove Press’s film division, which distributed the work, Brakhage emphasized that he did not regard it in any sense as pornographic, but was worried that the film might tempt paedophiles to use the “old ploy” of defending exploitative material as art. Brakhage wrote that the film would “be preserved for a time of greater clarity, a time when love is distinguished from currencies, enslavement and horror.” This passage from access to scarcity by the will of the filmmaker will be the topic of my next post, which will deal with a filmmaker who also – though for entirely different reasons – withdrew his work from distribution with a hope for a more hospitable future audience: Gregory Markopoulos.

All information concerning Brakhage’s involvement with Grove Press comes from the Grove Press Records at Syracuse University. Bruce Conner’s Ford Foundation application is a part of the Bruce Conner Papers at the University of California, Berkeley. All Canyon Cinemanews back issues were consulted at Anthology Film Archives. A special thanks to these institutions and the individuals who manage their collections.

Erika Balsom is assistant professor of film studies at Carleton University and author of Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, forthcoming this spring from Amsterdam University Press. Her brief history of the limited edition as a model of sale, “Original Copies: How Film and Video Became Art Objects,” will appear in Cinema Journal this summer.