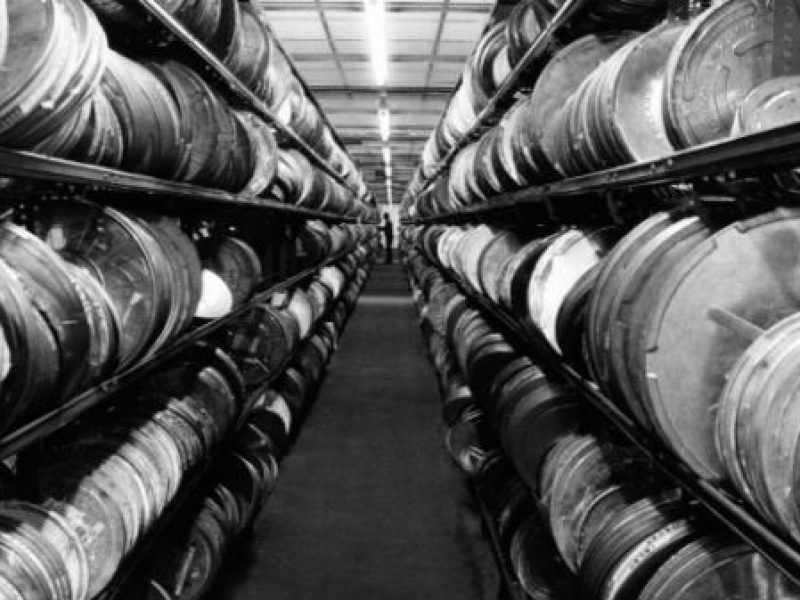

The Orphan Film Symposium, under the direction of Dan Streible, has championed a broad range of moving image culture since 1999. Firmly established in the international parlance of film archives, ‘orphan films’ referrers to the huge array and variety of material ostensible abandoned by its owner or caretaker, which can include anything from amateur and home movies, outtakes and alternative versions, unreleased films, industrial and educational movies, experimental films, silent-era productions, test reels, advertisements, etc. etc. The ‘Celebrating Orphan Films’ weekend hosted at the UCLA Film and Television archive in Los Angeles demonstrated the breadth of this area and critical import in championing this host of disregarded forms. Featuring presentations from a range of archivists and curators, the weekend exploded many supposedly separate traditions and often blurred the lines between different types of filmmaking, from industrial to experimental, personal to collective.

A variety of industrial films and adverts – often forgotten for the features or programmes they supported were – where shown, ranging from Saul Bass’s little known Bauhaus influenced commercial work to the psychedelic early motion capture adverts of Robert Abel & Associates (in particular a mind blowing 7UP advert) and fragments from the 27 million feet of Hearst’s Metrotone Newreel, made between1914 and 1967 held at UCLA. As well as rare coverage of the Vietnam war and a ‘futuristic’ fashion show in London with designs for the 1980s, they also showed the staggering footage of the Watts riots, with burning buildings and deserted streets patrolled by national guardsmen, while the voiceover dismissed any racial or political motivation for the civil unrest. One of the most surprising films of the weekend though was from the University of Southern Carolina’s collection of films donated by the Chinese Embassy in Washington. The truly amazing Light Cavalry Girl (dir. Jie Shen, 1980), a short documentary film, depicts an all-female sychronised motorbike squad, cruising through country roads and striking poses in their matching pink tracksuits while riding through a flower garden.

A very different type of news film, which may not ever have ever been shown was Fox Movietone’s ‘NYC Street Scenes and Noises’ made in 1929 with documents various Manhattan streets. The film was made to record the activities of the Noise Abatement Commission and their ‘traveling noise’ laboratory which monitored sound levels throughout the city. The lab obviously attached the curiosity of passersbys, who gather in groups and looking inquisitively at the camera expecting something to happen, not aware that their own presence and congregation would become the key event of this insight in the 1920 street culture.

Mark J. Williams, singled out the particular quality of unedited news footage in his presentation of a KTLA-TV newsreel film from the 1970s. The raw footage he argued could be appreciated for the historical events it records (in this case including the Roman Polanski hearing, Mary Pickford’s death and a Cesar Chavez press conference) but also for what he called the footages “quotidian anti-classical aesthetics.” The most striking material he present was of a protest by African American women outside the LAPF police station in 1979. The silent vigil, recorded with synch-sound which captures only the women’s footsteps, was held to protest the death of Eulia Love, who was shot in front of her house for allegedly resisting arrest by LAPD officers. This was an underreported incident, and the protest, as Williams stated, was covered even less, making this elegant, unresolved footage all the more remarkable, particularly in relation to the patronizing editorializing voice-over for the Watts riot footage from Hearst’s News of the Day.

The ‘Madison News Reel,’ is one of the most enigmatic Orphan film discoveries. Believed to have been made in 1932, the film, as Academy Film Archive curator Sean Savage explained, is both not a newsreel and was not shot in Madison. Instead it’s an early found footage collage – juxtaposing absurdist intertitles with various street scenes and observational footage. The jokes often revolve around specific personalities or occurrences from 1932, such as the solar eclipse that year which also had a marked effect on Joseph Cornell and his film ‘Rose Hobart’, widely regarded as one of the earliest found footage films. Presented by the ominous sounding ‘Bureau of Commercial Economics’, a largely forgotten but historically active non-theatrical distributor in the late silent period, the film is a rare example of what might be regarded as ‘local’ film culture.

Fellow Academy Film Archivist Mark Toscano discussed some of the problems of archival discoveries in the case of the ‘Snail Film’ (1972). This single shot slow-motion film of a snail being hit with a hammer was discovered on a reel kept by the filmmaker Robert Nelson and belongs to Chris Casady, a former student of his from Calarts. Intrigued and captivated by this peculiar and confrontational film, Mark showed and discussed it with people and until he discovered that his ‘Snail Film’ was actually only a test for Chris’s final film which incorporates this and other footage into an absurd apocalyptic explosion of material, entirely different to the single short ‘version’ on Roberts reel. Bill Brand of BB Optics discussed his work on David Wojnarowic’s notorious film ‘Fire In My Belly’ (1986-87) and the various versions of it that exist. Brand restored the film along with others works by Wojnarowic prior to the widely reported controversy regarding the withdrawn of this film from the Hide/Seek at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington last year. Yet the version of this film excluded from the show and exhibited internationally as part of a campaign against censorship, is not Wojnarowich’s original film that Brand restored for the estate and Fales Library at NYU, but a sanctioned reedit for the show leaving the 13 minute silent version of ‘Fire in my belly’, as Brand argued, in danger of being “orphaned in public.”1

Brand also presented the great early super8 films of Andrea Callard, a key participant in the New York art scene in the last 70s and early 80s and crucial member of the Collaborative Projects Inc. (Colab). Made with a synch sound camera her films are playful and modest, inspired in equal parts by the chance strategies of John Cage and I Ching and feminist politics. Often revolving around sound image relationships, such as in ‘Lost Shoe Blues,’ when she improvises a surreal blues song, or in ‘Flora Funera (for Battery City Park)’ in which she creates the soundtrack by throwing stones at the exposed steel rods on an abandoned construction site. Her films represent a parallel side to the more widely known No Wave works of this period, especially ‘11 thru 12’ (1977) which consists of a series of asides to the camera addressing various issues such as how maturity can be quantified by measuring your collection of National Geographic’s, to demonstrating how to hail a taxi or walk on your hands in the sea.

The Outfest Legacy Project at UCLA, which is dedicated to preserving key works from the LGBT community and filmmakers, such as the recently restored rapturous films of Tom Chomont and the anonymous amateur film Mona’s Candle Light (c. 1950), one of the only records of Mona’s lesbian bar in San Francisco. Drag king Jimmy Reynard and singer Jan Jensen perform in the hushed environment of the bar in this intimate record of lesbian culture on its own terms prior to Gay liberation movement. In stark contrast to this Pat Rocco’s pastel coloured romance ‘Ron and Chuck in Disneyland Discovery’ (1969) is a jubilant romance between two young men filmed covertly in the midst of holidaying families at Disneyland, an incredibly sweet, touching and gently subversive film.

The LA Rebellion film movement, which provided a new model for Black cinema and independent filmmaking in America in the 1970s, is finally being recognized by a new research, publishing and international screening programme. The scale and importance of this movement is only just being understood now, as Alleyson Field one of the project curators at UCLA stated, they went from believing there were maybe 10-15 filmmakers including figures such as Charles Burnett, Haile Gerima and Julie Dash to exploring the work of over 50 filmmakers previously ignored or forgotten. One of the films they have rediscovered is a super8 student film by Bernard Nicolas, called ‘Daydream Therapy’ (1980), a story of black resistance in the face of white oppression, the films progresses in parallel to its soundtrack which moves from restrained Nina Simone to the Afrocentric free-jazz of Arche Schepp. Prior to this movement which had its origins in the Ethno-Communications programme at UCLA, the research librarian Mayme A. Clayton helped establish the university’s African-American Studies Center in 1969. Yet when denied the resources required to properly collect these rare and quickly vanishing materials, she took early retirement and began what is now the largest privately held collection of African-American historical materials in the world. The Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum holds an unprecedented collection of films related to the African American experience. The collection includes the fascinating home movies of musician, performer and pioneering black aviatrix Marie Dickerson Cocker. Filmed between 1942 and 1953 the films depict her life on the road, her friends and parties and her amazing array of outfits she happily shows off for the camera.

‘The Unshod Maiden’ (1932), is a single reel re-edit of female director Lois Webber lost 1916 film ‘Shoes.’ Weber was one of the key filmmakers of the 1910s and 1920s and the highest paid director at Universal where she produced a distinct brand of socially-engaged popular cinema. Yet this reel, one of a number made in the 1930s which re-edited silent films, features a vindictive mocking voice-over which satirise the original film both for its pre-sound acting style as well as its story of woman’s struggle for wage equality. The film seems to illustrate the beginning of the cruel dismissal of Weber and her social ambitions for filmmaking from the history of cinema. Thankfully the footage contained in ‘The Unshod Maiden’ is now being used to create a full restoration of Weber’s original film. The ideology of early cinema in America is fascinating as this new popular medium was utilized by a wide range of political, social and ethnic groups. Yet left wing filmmaking in particular was largely been wiped out by McCarthy and the Hollywood Black List in the 1950s which not only stopped filmmakers from working but also began the process of rewriting film history to exclude the cinema of the Left.

Two striking examples of the handling of left wing ideology in early cinema were presented at the close of the Orphans weekend, the striking anti-Bolshevik film ‘The Transgressor’ (1918) made by the Catholic Art Association and the remarkable collectively made labor film ‘The Passaic Textile Strike’2 (1926) made by the International Workers Aid. Even through ‘The Transgressor’ pivots on the demonized figure of the Bolshevik aggravator who manipulates the workers and nearly leads them to lynch their mill owner. On the other hand ‘The Passaic Textile Strike’, which is prefaced by a narrative prologue which puts the workers issues in to a deliberately melodramatic framework, largely consists of documentary material of the striking workers, their families and the workers aid efforts. The documentary footage, in and of itself an invaluable social record, is also constructed to explicitly counter the stereotypes of unions and workers utilized by films such as The Transgressor. In the newly discovered fifth reel, the film presents the children of the strikers and the communities efforts to educate, feed, clean and entertain them, including a clearly staged baseball match (to show that the immigrant workers are true ‘Americans’). A rich and fascinating film, it is a glimpse into the complex politics of representation and counter-presentation being played out in the popular cinema.

George Clark

1 The Hide/Seek website which co-ordinated the screenings of Fire In My Belly has added details on the various versions as well as a statement from Marvin Taylor, Director of Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University clarifying the various versions of the film that exist. http://www.hideseek.org/versions/

2 Only 6 out of the 7 reels of the film are known to exist, yet it remains one of the most complete labour films made in America to survive. The 5th reel, the latest to have been discovered was believed lost until recently. The prologue of the film is available to download at http://www.archive.org/details/passaic_textile_strike_1926